Abstract

The Disney Princess phenomenon has been well documented in recent years, and results of such studies indicate that these characters exert a powerful influence on children’s media and self-identity, defining “girlhood” in a highly gendered fashion, rife with stereotypical representations. And for girls who have grown up with this princess-like beauty ideal, body dissatisfaction is at an all-time high. Increased media exposure is related to children’s preference for thin adult figures that could represent their future selves. And, unfortunately, social comparison to these figures has resulted in a proliferation of eating disorders. To examine this intersection of the Disney Princess and the prevalence of eating disordered lifestyles, this case study presents a thematic analysis of anonymous Twitter user @BunnieJuice, a self-professed Disney princess fan and active anorexic. Through the analysis of her 11 months of tweets, pictures, and retweets, three overall themes emerged: harmful thinspiration, self-destructive behavior (i.e., starvation, binging, and cutting), and negativity aimed at others. Examples of Disney-inspired tweets include Disney princess “thinspo” pictures, the use of a Tinker Bell box for her cutting instruments, and quoting from Disney movies to others that have wronged her. @BunnieJuice has clearly co-opted the princess image to justify her eating disordered lifestyle and to motivate herself to continue this behavior.

Introduction

The so-called Disney Princess phenomenon has been well documented in recent years (e.g., Wohlwend, 2009; England, Descartes, & Collier-Meek, 2011), and results of such studies indicate that these characters exert a powerful influence on children’s media and self-identity, defining “girlhood” in a highly gendered fashion, rife with stereotypical representations. And for girls who have grown up with this princess-like beauty ideal, body dissatisfaction is at an all-time high. A clear danger of this negative self-view is the propensity toward an eating disordered lifestyle, and it appears that access to social media platforms can add an extra “push” toward anorexia or bulimia. Whereas in the past, girls and young women may have shared their body image woes within their circle of friends and family, the advent of social media has increased the potential for community-building around topics such as body dissatisfaction and eating disorders. In fact, research on the Twitter platform demonstrated that many eating disordered tweeters congregate on specific “pro-ana” (i.e., pro-anorexic) public profiles to offer tips and suggestions for being “successful” anorexics (Ryan & Hovis, 2015).

The availability of such public profiles to young audiences is particularly troubling when social media content producers weave the “princess myth” into their pro-eating disordered lifestyles. The research on participatory culture (see Jenkins, Purushotma, Weigel, Clinton, & Robison, 2009) reminds us that in this era when one person’s obsession with princesses and thinness is played out online, it is no longer a solitary activity; it begins to create a community of like-minded individuals. And with the princess obsession beginning earlier and earlier for girls, and access to social media remaining virtually unchecked, we create a culture in which childhood eating disorders can run rampant in a supportive environment.

The objective of this paper, then, is to examine the relationship between the obsession with Disney princess-prescribed notions of beauty and the propensity toward eating disorders. It takes a case-study approach, focusing on the 11-month Twitter journey of @BunnieJuice, a public tweeter who proudly communicated in text and images her affinity for Disney princesses and her struggle with anorexia. What aspects of her messages can be linked to the Disney-fied notions of beauty? The analysis is informed by the literature outlined below on media and body image, and constructivist and cultivation theory.

Media, Body Image, & Eating Disorders

Increased media exposure is clearly related to children’s preference for thin adult figures that could represent their future selves (Harrison & Hefner, 2006) and self-reported body dissatisfaction and eating disorders proliferate after the introduction of media, particularly for young girls. Groesz, Levine, and Murnen’s (2002) meta-analysis of 25 experiments testing the effects of exposure to ideal-body media imagery on various indices of body image found a modest but significant drop in body satisfaction, and the effect size was greater for those under age 19. Hargreaves and Tiggemann (2004) found that girls 13-15 who viewed 20 television commercials containing “idealized images” reported significant body dissatisfaction. More telling, however, is research by Harrison (2001) that found adolescents who viewed televised portrayals of thinness being rewarded felt dejected, and those who viewed a portrayal of fatness felt agitated. Harrison (2001) argued that dejection and agitation are antecedents to eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia; continued exposure to thin-ideal media messages, therefore, could lead to bulimic and anorexic patterns of eating.

Even print media is a culprit. Stice, Spangler, and Agras’ (2001) experiment determined that bulimic symptoms increased for girls with low peer/parent support who received a subscription to Seventeen Magazine for 15 months. Harrison, Taylor, and Marske (2006) found that same-sex ideal-body pictures altered the way college students ate in from of same-sex peers. Stice, Shupak-Neuberg, Shaw, and Stein (1994) demonstrated that media exposure predicts disordered eating via a chain of variables such as gender-role endorsement, ideal-body stereotype internalization, and body dissatisfaction. And Harrison and Heffner (2006) found in a longitudinal study that girls aged 7-12 who viewed high levels of television for a year scored higher on a measure of disordered eating one year later than girls who did not watch as much television. Clearly there is a relationship between media exposure and propensity toward disordered eating.

More recently, researchers have set their sights on online content. Norris, Boydell, Pinhas, and Katzman (2006) were the first to systematically examine pro-eating disorder websites, and their textual analysis of 12 pro-ana sites highlighted the themes of control, success, perfection, isolation, sacrifice, transformation, coping, deceit, solidarity, and revolution. Building upon this work, Bardone-Cone and Cass (2007) conducted the first experiment examining the immediate effects of viewing such websites. After college-aged women viewed pro-eating disorder websites, they were more likely to score higher on “likelihood to diet” and “compared self to images during website” and lower on “academic self-esteem” and “appearance self- efficacy” than peers who viewed either a fashion website or home décor website. Whereas these effects were found immediately after viewing websites, cultivation theory predicts that exposure over time can lead to a gradual and permanent change in attitude and behavior. Frequent viewers of such websites could easily begin a lifestyle of disordered eating, particularly when paired with membership in an online community that perpetuates these ideals.

The message spreads, and with it, eating disorders flourish. We know that 20 million American women and 10 million American men suffer from some form of clinically significant eating disorder at some time in their lives (Wade, Keski-Rahkonen, & Hudson, 2011). Sadly, a meta-analysis of 50 years of research on anorexia nervosa demonstrated the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder (Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales & Nielsen, 2011). And the constant exposure to thin-ideal messages featuring unhealthy or unattainable female bodies, in conjunction with regular participation online with users who are promoting an eating-disordered lifestyle, can have devastating consequences (Harrison & Hefner, 2011).

Disney & the Princess Effect

When most people think “princess,” they think Disney. Indeed, Stone (1975) noted that “Disney’s influence on the princess narrative is so powerful that few American women can name fairy tale heroines other than those that have been immortalized in film by Disney” (p. 43). As the “most successful property for Disney Toys” (Disney Consumer Products, 2007, para. 3), the Disney Princess franchise targets girls beginning in preschool. Beyond the actual films, parents can purchase toys, collectibles, clothing, video games, books, makeup kits, school supplies, costumes, and all types of household goods (e.g., bed linens) featuring the twelve princesses: Snow White, Jasmine, Belle, Pocahontas, Mulan, Cinderella, Ariel, Aurora, Anna and Elsa (from Frozen), Merida, and Rapunzel. And as Baker-Sperry and Grauerholz (2003) pointed out, regardless of the product, the consistent requirement for a princess in this franchise is that she must be beautiful. Wohlwend (2009) noted that the Disney Princess brand has worked to homogenize their princesses by highlighting their common beauty ideal at the expense of their variations in personality and power.

Blaise (2005) pointed to this princess ideal as the archetype in our American cultural norm of femininity and beauty in an ethnographic study of kindergarteners. During “princess play,” girls focused primarily on beauty ideals: “The value that a small group of girls placed on being beautiful and pretty became evident in the dramatic play are while they were pretending to be princesses” (p.77). And this focus on Disney princess-esque beauty can follow children far beyond childhood. As an “enduring lifestyle brand,” the Disney Princess franchise now offers quinceanera gowns, prom and bridal dresses, and a makeup line at Sephora (Cioletti, 2014, p. 74).

Giroux (1995) explained that Disney films “inspire at least as much cultural authority and legitimacy for teaching specific roles, values and ideals than more traditional sites of learning such as public schools, religious institutions and the family” (p. 25). And researchers such as Lacroix (2004) have determined that the typical Disney princess is animated as small-waisted with delicate limbs and full breasts, and generally with extremely pale skin. As Garside (2006) noted, Disney animators created “pleasure in looking” at their princesses (Mulvey’s (1989) concept of “scopophilia”) by using socially-accepted images of female beauty when creating characters, turning to popular film actresses for inspiration (p. 34). Bell, Haas, & Sells (1995) explained that Disney’s “animated heroines were individuated in fair-skinned, fair-eyes, anglo-saxon features of Euro-centric loveliness, both conforming to and perfecting Hollywood’s beauty boundaries” (p. 110). So it should come as no surprise that girls who grow up with the Disney Princess brand have body-image issues when they continuously compare themselves to impossible beauty standards.

Theoretical perspectives

Researchers argue that the internalization of socio-cultural identity and appearance ideals – most of which come from the media – contribute to the development of body image issues, concern about one’s weight, and, potentially, eating disorders (Sands & Wardle, 2003; Streigel-Moore & Cachelin, 1999; Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999). Corsaro (1997) noted that children especially “quickly appropriate, use, and transform symbolic culture as they produce and participate in peer culture” (p. 100). The constructivist approach and cultivation theory both speak to this process.

The constructivist approach is a cognitive theoretical model that proposes children construct their beliefs about the world based upon their own interpretations of observations and personal experiences (Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002). This would suggest that viewing skewed or unattainable standards of beauty would influence their own ideas about societal beauty expectations. Gerbner’s cultivation theory also posits a negative effect of viewing unrealistic beauty standards (see Gerbner, Gross, Morgan, & Signorielli, 1994). Cultivation takes a more longitudinal view, referring to the cumulative effect over time of viewing media content. If a child is continuously exposed to certain mediated models of beauty, she will begin to believe that the “media version” of beauty is one to which she should aspire. This may have a direct effect on their attitudes and behaviors.

Both the constructivist approach and cultivation rely on viewers’ interpretation of the world around them in the formation of identity and beliefs. In Wohlwend’s (2009) work on Disney toys, she focused on the “identity messages” inherent in the merchandise itself:

Identity messages circulate through merchandise that surrounds young consumers as they dress in, sleep on, bathe in, eat from, and play with commercial goods decorated with popular culture images, print, and logos, immersing children in products that invite identification with familiar media characters and communication gendered expectations about what children should buy, how they should play, and who they should be. (p .57)

In examining Disney artifacts, Wohlwend (2009) pulled from sociocultural theories of identity, furthering Rowsell and Pahl’s (2007) work on “sedimented identities” (that reflect a child’s decisions about identity performance based on perceived cultural norms) and extending it to commercially produced merchandise, calling it “anticipated identities,” or identities that have been “projected for consumers and that are sedimented by manufacturer’s design practices and distribution processes” (p. 59). In the current study, the anticipated identities projected by Disney about their princess line are those of impossible beauty standards. Thus, avid Disney princess fans adopt these identities as the ideal and then struggle to live up to those criteria.

Research on social comparison theory also supports this notion. Festinger (1954) explained that people tend to assess their own opinions and potential by comparing themselves to others. We search for information about others – their behaviors, social standing, and opinions – for purposes of self-judgment, assessing the “correctness” of our own opinions, beliefs, and capabilities in relation to theirs (Sulls & Wheeler, 2012). Many times these “others” can be found in mediated representations, and many times those representations are somehow warped or altered (i.e., photoshopped images). So when media users compare themselves to these images, they are setting themselves up for failure.

Research Questions and Methodology

If, indeed, as Baker-Sperry (2007) believes, a girl’s interpretation of beauty standards is “most effectively negotiated at the level of interaction where understanding is conceptualized, organized and reaffirmed through peer identity” (p. 717), then social media is the most appropriate place to begin taking a closer look at how this interpretation can get tangled up with the propensity toward eating disorders. What is it about the princess mythology that seems to strike a chord with girls who suffer from eating disorders? How is the Disney Princess model related to living a life of disordered eating?

To begin to address the research questions, this analysis used a case study approach, focusing on the twitter feed of a self-confessed Disney Princess fan living an eating-disordered lifestyle.

Thematic analysis

An applied thematic analysis (ATA) approach was used to analyze the data. ATA is defined by Braun and Clarke (2006) as a qualitative analytic method for “identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data. It minimally organises and describes your data set in (rich) detail. However, frequently it goes further than this, and interprets various aspects of the research topic” (p. 79). Themes capture “something important about the data in relation to the research question” and represent some level of “patterned response or meaning within the data set” (p. 82). The ATA analysis methodology differs from the grounded theory approach in that it does not preclude theoretical development per se, but the resulting output is most likely not a theoretical model; rather, its primary goal is to “describe and understand how people feel, think, and behave within a particular context relative to a specific research question” (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2011, p. 13).

Procedure

The analytic approach of ATA is systematic. Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guide to the six phases of conducting ATA included:

- Become familiar with the data

- Generate initial codes

- Search for themes

- Review themes

- Define and name themes

- Produce the report

Braun and Clarke’s (2006) approach provided the necessary structure for this ATA. Of course,

As Guest et al. (2011) noted, the codebook itself is never finalized until the coder has finished with the last of the text; revisions of initial interpretations continuously occurred, even throughout phases five and six.

Sample Selection

@BunnieJuice was discovered during data analysis for a previous study (Ryan & Hovis, 2015), and was the impetus for the initial investigation into the Disney/eating disorder phenomenon. Thus, her Twitter feed is used as a case study for this project. Her feed contains posts from July 13, 2013 until June 17, 2014, at which time they stopped. @BunnieJuice’s tweets were captured in screenshots and printed for this ATA to aid in Braun and Clarke’s (2006) step three: the search for themes. The themes that emerged from the data are discussed at length below.

Analysis

After the analysis was complete, elements that emerged could be categorized in three overarching themes: harmful thinspiration, self-destructive behavior, and negativity aimed at others. Each of these themes is discussed at length below. Both original tweets and retweets were considered for the analysis.

Harmful Thinspiration

The category of harmful thinspiration included both text and visual elements that speak directly to @BunnieJuice’s daily struggle with keeping up her eating disordered lifestyle. Images ranged from visuals related to specific body parts to still-frames from animated Disney films. Much of the text included in this category is negative self-talk, and some of that self-talk involves self-comparison to Disney princesses.

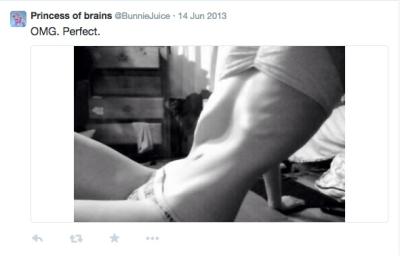

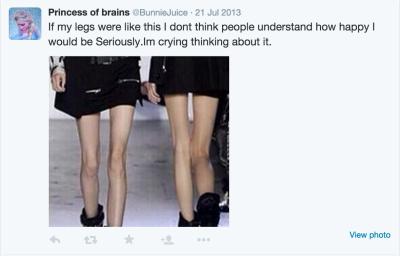

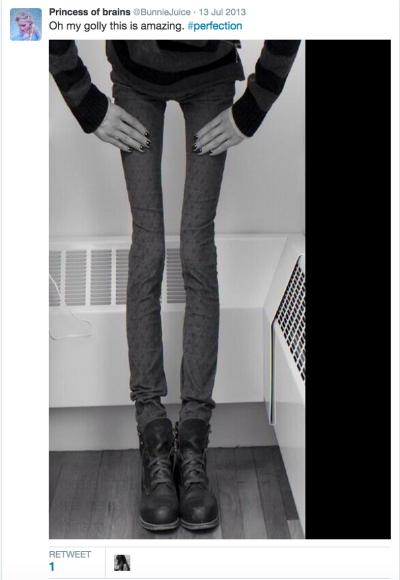

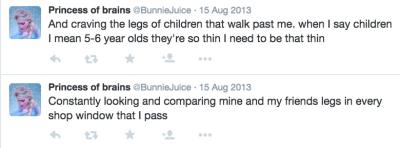

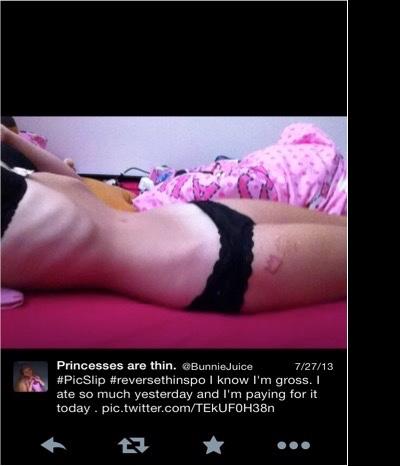

Visual representations of bodies and body parts are consistently used by @BunnieJuice as inspiration to “stay on track.” It is all too common to see pictures of collarbones, hipbones, thighs with large gaps between them, and ribs on thinspiration websites and social media accounts, and @BunnieJuice is no exception. These pictures set the bar for perfection in the eyes of the tweeter and her followers, and are marked with aspirational captions:

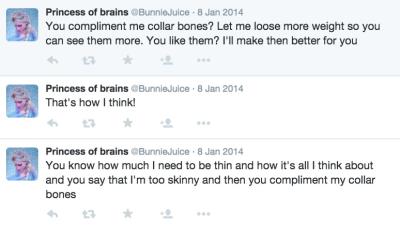

Several tweets and retweets also reference body parts in text as well, such as:

One series of tweets (read from bottom to top chronologically) is directed at a current boyfriend:

But chopping a body up into its parts is also a way to further objectify women. As Kilbourne (2010) noted, once women’s bodies are reduced to their parts, they become a “thing” rather than a person. By presenting bodies in pieces rather than a whole, @BunnieJuice appears to be viewing herself in this same fragmented way. She judges herself based upon her parts, and continuously finds herself lacking.

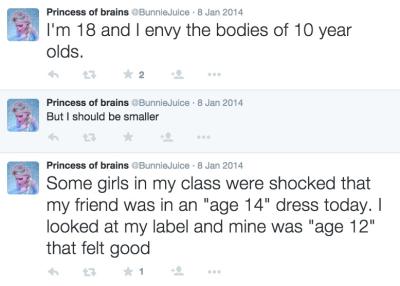

@BunnieJuice takes this obsession with bony body parts a step further and integrates her Disney princess obsession into her thinspiration images. When the project began, her “name” on Twitter was “Princesses are thin” and she later changed it to “Princess of brains” after about six months. Her profile picture is Queen Elsa from Frozen:

and her cover photo now features part of Snow White’s body:

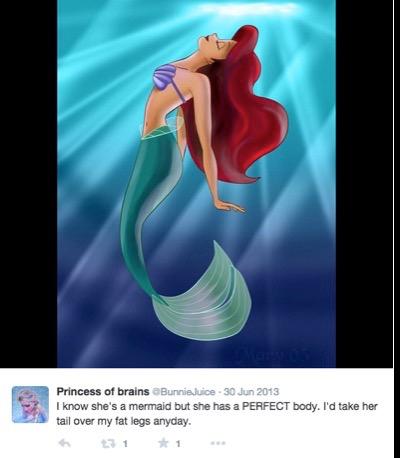

When this project began, her cover photo featured Ariel from The Little Mermaid (note the caption):

In a series of tweets she explained her connection to Queen Elsa:

Another one of the images on her timeline is a picture of Ariel’s body:

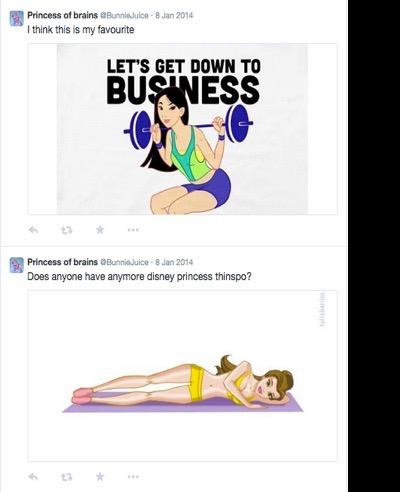

She has also posted two “Disney princess thinspo” images: one of Belle from Beauty and the Beast and another of Mulan. And she is on the hunt for more “Disney thinspo;”

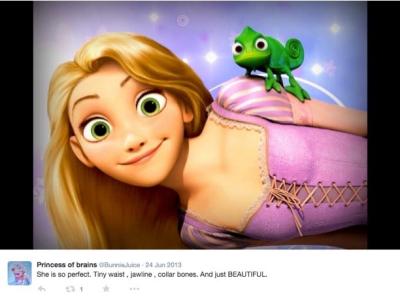

And Rapunzel makes an appearance:

Lastly, an item featuring Tinker Bell from Peter Pan is highlighted (see section below for further discussion of this item).

Here @BunnieJuice is using animated characters’ bodies – bodies that were drawn, created by an artist – as inspiration. These bodies do not exist in reality. Even worse than worshipping photoshopped bodies in images, which at least began as actual humans, an obsession with animated bodies is doomed to fail. How could she ever measure up to a standard that does not even exist?

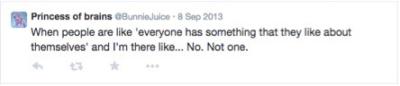

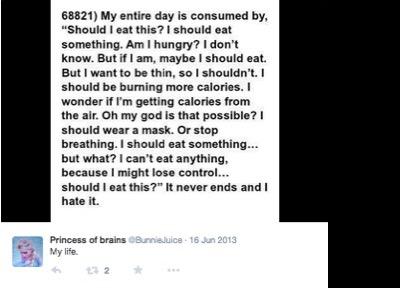

Negative self-talk is extensive in @BunnieJuice’s twitter feed. She beats herself up virtually every day in some way, chastising herself for not living up to impossible standards. One tweet sums up her attitude perfectly:

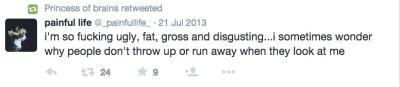

She is constantly referring to herself with self-loathing in tweets and retweets:

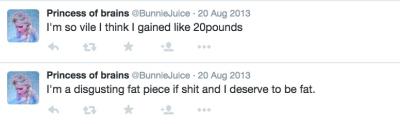

She clearly also desires to look like a young girl:

Again, an impossible standard. And, sadly, it seems that even the thought of eating or being around food causes her anxiety:

This girl has a clear vision of what “beautiful” means to her, and it is reflected in these tweets and images. Reading her twitter feed, one can almost feel her anxiety, verging on panic, while she fights these daily battles with herself:

There are very few images of @BunnieJuice herself, but one look at the picture of herself she does choose to share (discussed below) demonstrates that this is a girl who needs help. She is painfully thin and, as outlined below, inflicts pain on her body almost daily. Using princesses as inspiration can only lead to disappointment.

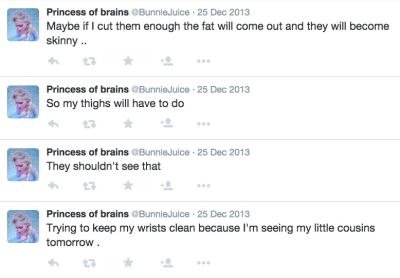

Self-destructive Behavior

Unfortunately, @BunnieJuice’s obsession with Disney princesses does not end with using images as inspiration to refrain from eating. @BunnieJuice is a cutter. Cutting is considered a psychological condition known in the DSM-V as a Non-Suicidal Self Injury (NSSI) in which:

In the last year, the individual has, on 5 or more days, engaged in intentional self-inflicted damage to the surface of his or her body, of a sort likely to induce bleeding or bruising or pain (e.g., cutting, burning, stabbing, hitting, excessive rubbing), for purposes not socially sanctioned (e.g., body piercing, tattooing, etc.), but performed with the expectation that the injury will lead to only minor or moderate physical harm. The absence of suicidal intent is either reported by the patient or can be inferred by frequent use of methods that the patient knows, by experience, not to have lethal potential. (Alderman, 2010, np)

Typically, this type of intentional self-injury is associated with feelings of anxiety, depression, or self-criticism and is done purposefully to relieve negative feelings or interpersonal difficulties (Alderman, 2010). Interestingly, Sax (2010) reported that most girls who engage in this behavior do not want to get caught; they hide their injuries. And yet @BunnieJuice chooses to celebrate her cutting, albeit anonymously on Twitter.

And she has linked her cutting behavior with her Disney princess obsession. As noted above, her cover photo is of Snow White. But this version of Snow White has multiple slash marks on her outstretched arm (see above). Clearly, @BunnieJuice has altered the image to fit her obsession, casting perhaps the most innocent of Disney Princesses as a cutter like her. Her previous cover photo featured Ariel and she had altered that image as well, making it appear as if Ariel had slash marks up and down her arms. She also keeps her supply of razor blades and needles in a small box featuring Tinker Bell from Peter Pan, which she proudly displays:

Additionally, @BunnieJuice posted a picture of herself, pointing out that she has carved the figure of a crown on her leg:

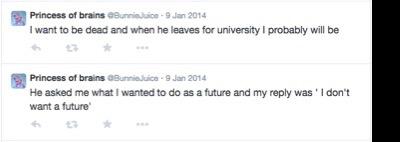

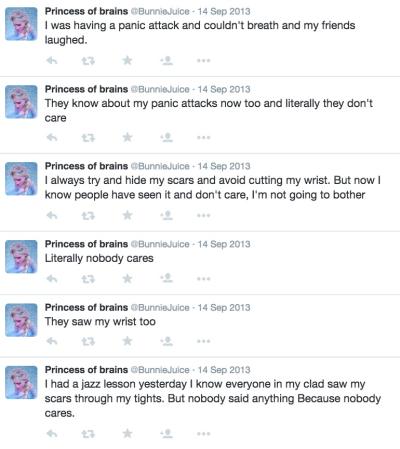

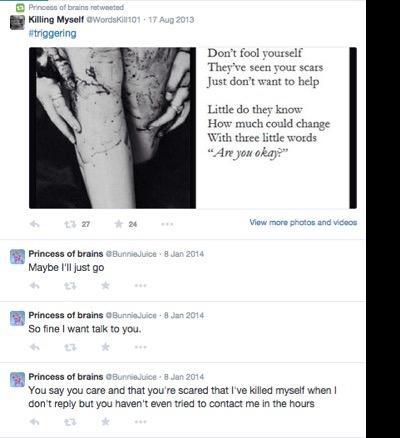

In addition to her cutting behavior, many of @BunnieJuice’s posts communicate a

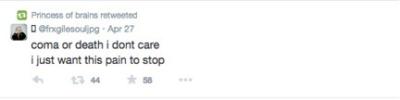

depressed state, some bordering on suicidal. Many tweets have a resigned or fatalistic feel to them, as if she has given up on ever being able to reach her goals (as unhealthy as they may be). It is interesting to note, however, that cutting expert Sax (2010) explained that typical cutters are not, in fact, suicidal. His work with psychiatric patients typically finds that cutters generally hide their wounds, and that, unlike conventional wisdom dictates, cutting is not a “cry for help” in the same way a threat of suicide may be. But this cutter states several times that she has suicidal thoughts with tweets and retweets such as:

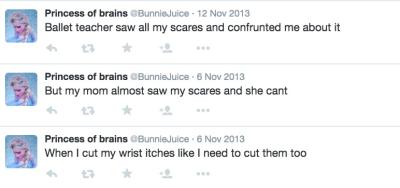

Many tweets focus on her cutting behavior. Most have an almost apologetic tone to them, almost as if she’s confessing and asking forgiveness for the behavior. Examples include:

Often she references her scars (which she frequently misspells as “scares”) and trying to hide them from family, friends, and teachers:

Hiding the scars indicates that, as Sax (2010) noted, she wants to hide her wounds. It is not necessarily a cry for help. It appears, instead, to be a method of dealing with the anxiety about her eating disorder. As she noted in one series of tweets:

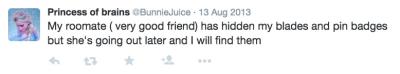

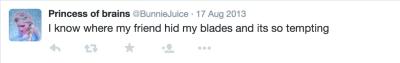

Interestingly, it appears as if one of her friends is aware of her cutting behavior and tries to hide her blades. On two occasions, she tweets about this directly:

@BunnieJuice is determined to cut. And whereas she appears to be hiding this behavior from most people, she freely discusses it in the very public Twitter forum. Perhaps the anonymity of Twitter gives her the confidence to confess.

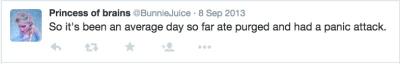

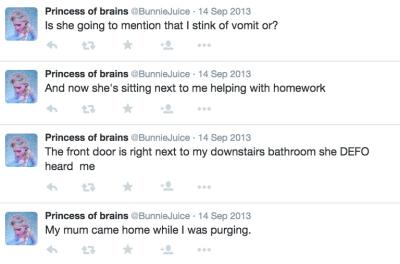

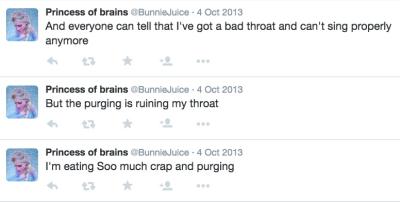

Her cutting behavior is not the only self-destructive activity she chronicles. @BunnieJuice also keeps her readers up-to-date on her binging, purging, and starvation. She tweets:

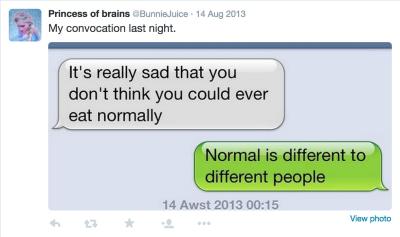

Her discussion of her purging behavior is so cavalier at times, almost as if she sees this anorexic and bulimic behavior as normal. It is certainly a normal part of her every day experience; as she tweeted:

And when she does eat, her go-to is chewing gum:

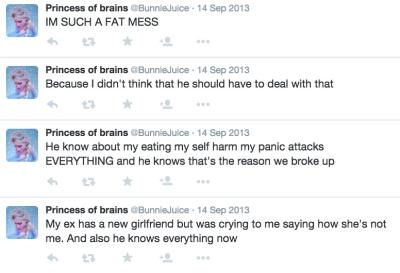

But she is well aware that she is suffering from an eating disorder and that her cutting behavior is not healthy. One tweet referencing her ex-boyfriend states,

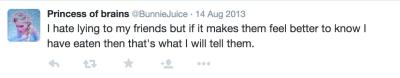

And she admits to her secretive lifestyle, explaining:

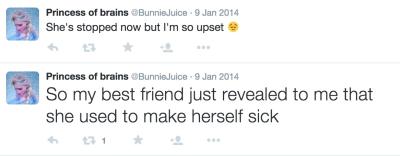

And upon finding out that her best friend lived a similar lifestyle to hers, she was panicked:

So to @BunnieJuice, self harm is okay for her but not for those she loves.

Negativity Aimed at Others

Not all of @BunnieJuice’s tweets focus inward. In between self-critical tweets and inspirational pictures of thin models are messages aimed at others. This category of tweets does not speak to the “princess” issue as directly as the first two categories, but it certainly adds some context to her words, images, and actions captured above. Often, these tweets come in groups of back-to-back messages on the same day aimed at the same person. She lashes out at ex-boyfriends, current boyfriends, friends, teachers, and her mother.

@BunnieJuice very often writes accusatory tweets that condemn her boyfriend’s lack of communication. Followed chronologically, readers watch the progression of these tweets go from frustration, to anger, to out and out rage. For example, on her last day of tweeting she posted a series of 23 back-to-back tweets all aimed at her boyfriend. They began as annoyed messages (e.g., “If you didn’t plan on meeting up with me you shouldn’t have brought it up OMG you don’t understand what you’re doing to me”) and progressed to anger (e.g., “When I’m no crying im raging and panicking”), then she calls him a derogatory name in all caps in a rage, and finally falls apart emotionally (e.g., ” You don’t care you simply do not care” and “I literally just feel broken.”). In these moments, @BunnieJuice is using Twitter as a surrogate for her boyfriend; she tells her followers the things she cannot tell him. Here is a shorter example of how her concern quickly turns to anger:

A series of tweets like this reads more like a cry for help than anything as she specifically references her disease and her inability to ask him for help; she believes that he should just know that she needs him to step up.

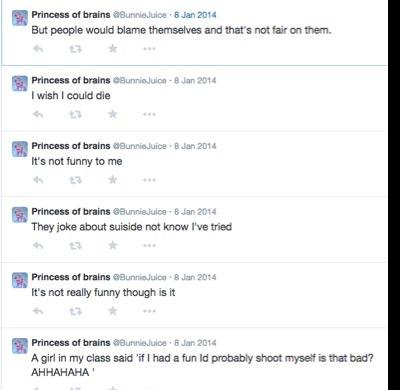

January 8 was a particularly bad day for @BunnieJuice. She tweeted 141 times that day, lashing out at her crush, her friends, her mom, and her classmates. She began this rant with by lamenting she hadn’t seen her ex-boyfriend for over a month, that he does not care, and that he assumes she is okay and she’s clearly not. She pleads with him to talk to her in a series of 31 tweets, and suddenly she shifts gears, tweeting that a girl in her class was talking about suicide that day:

She then posted a series of “I’m so disgusting” tweets, and then shifted back into pleading with her ex to love her.

Here she weaves her Disney obsession into her rant. She noted that Queen Elsa (see above) makes her feel better about anxiety and eating. She followed up with a retweet from Disney Words:

Ostensibly this message is aimed at her ex-boyfriend. But then she threatens to kill herself again:

If this series of tweets is an insight into how this girl’s mind works, hopping from one anxiety- and self-loathing-filled thought to the next at lightning speed, one can only hope that she stopped tweeting on June 17 because she finally got the help she needed.

Discussion

@BunnieJuice sums up her 11-month journey on Twitter succinctly in one tweet:

Here is a young girl who plays out her inner turmoil on a social media platform that allows her to be anonymous, confessing her misdeeds to the world. She shares her thinspiration images (which are frankly horrifying to those not in her social media circle) and her struggles with self-esteem, fat-shaming herself when clearly she is anything but. She admits to self-harm, even posting pictures of a princess crown she carved on her leg. She angrily accuses others of ignoring her and her disease, while at the same time begging these people to love her. And much of this angst and heartache stems from an unhealthy obsession with Disney princesses. She holds herself to an impossible standard, comparing her body to those of animated characters, always looking for more “Disney princess thinspo.”

She calls herself a failure. But a human girl can never look like an animated princess, so she has doomed herself to fail from the beginning.

But is there room for hope here? Is there anything in @BunnieJuice’s Twitter feed that indicates that she is not beyond saving? She appears to be aware that her behavior is not “normal” and that her friends should be concerned about her. And she shows concern for a friend that is “reminding me of me” as she displays some eating disordered behaviors. So perhaps some hope shines through in between self-destructive tweets. And what to make of her sudden exit from Twitter? We can hope that the reason she stopped tweeting is that that someone finally did help her, and that she’s getting the treatment she so clearly needs.

Taken as a whole, however, the picture painted by this analysis is grim. Here is a young girl with a completely warped sense of reality and a completely unrealistic expectation of herself. She is setting herself up to fail: this “Disney princess” standard is unachievable. And she’s sharing this unrealistic standard with her community of followers, which is cause for concern. Future research can follow the # Disneythinspo breadcrumbs, searching for others who share this obsession and perhaps uncovering more about the connection between the princess mythology and the eating disordered lifestyle.

But perhaps the most disturbing element in this analysis is the connection between eating disorders and self-harming behavior. According to Favazza, DeRosear, & Conterio (1989), this link is not new. They stated that intermittent and repetitive self-injury is frequently seen in conjunction with, or as a replacement for, eating disorders. Their research on self-mutilating women found that 22% suffered from bulimia, 15% from anorexia, and 13% from both. A participant in Harris’s (2000) study on self-harm explained, “When I started to emerge from my anorexia, I needed some other way of dealing with the pain and hurt, so I started cutting instead. It is a way of gaining temporary relief. As the blood flows down the sink, so does the anger and the anguish” (p. 167). This explanation sounds eerily similar to @BunnieJuice’s experience, as played out on Twitter. In this age of social media, do we see more of this behavior? Perhaps we can we learn more about motivations for self-harm from sufferers of eating disorders in future social media research.

References

Alderman, T. (2010): Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: A new diagnosis? Psychology Today. Available online.

Arcelus, J., Mitchell, A. J., Wales, J., & Nielsen, S. (2011). Mortality rates in patients with Anorexia Nervosa and other eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 724-731.

Baker-Sperry, L. (2007). The production of meaning through peer interaction: Children and Walt Disney’s Cinderella. Sex Roles, 56, 717-727.

Baker-Sperry, L. & Grauerholz, L. (2003). The pervasiveness and persistence of the feminine beauty ideal in children’s fairy tales. Gender & Society, 17(5), 711-726.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., & Cass, K. M. (2007). What does viewing a pro-anorexia website do? An experimental examination of website exposure and moderating effects. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(6), 537-548.

Bell, E., Haas, L., & Sells, L. (1995). From mouse to mermaid: The politics of film, gender and culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Blaise, M. (2005). Playing it Straight: Uncovering Gender Discourses in the Early Childhood Classroom. New York: Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101

Cioletti, A. (2014). Forever princess. Global License. Available online.

Corsaro, W. (1997). The Sociology of Childhood. Berkeley, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Disney Consumer Products (2007). Toys. Available online

England, D. E., Descartes, L., & Collier-Meek, M. A. (2011). Gender role portrayal and the Disney princess. Sex Roles, 64, 555-567.

Favazza, A. R., DeRosear, L., & Conterio, K. (1989). Self-mutilation and eating disorders. Suicide & Life Threatening Behaviors, 19(4), 352-361.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison process. Human Relations, 7, 117-140.

Garside, C. (2006). Essentialized females animated: A feminist analysis of visual pleasure of two Disney heroines. International Journal of the Humanities, 3(6), 33.

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1994). Growing up with television: The cultivation perspective. In J. Bryant & D. Zillmann (Eds.), Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research (pp. 17-41). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Giroux, H. A. (1995). Animating youth: The Disneyifcation of children’s culture. Socialist Review, 24, 23-55.

Groesz, A. C., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1-6.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hargreaves, D., & Tiggemann, M. (2004). Idealized media images and adolescent body image: “Comparing” boys and girls. Body Image, 1(4), 351-361.

Harris, J. (2000). Self-harm: Cutting the bad out of me. Qualitative Health Research, 10(2), 164-173.

Harrison, K. (2001). Ourselves, our bodies: Thin-ideal media, self-discrepancies, and eating disorder symptomology in adolescents. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(3), 289-323.

Harrison, K., & Heffner, V. (2006). Media exposure, current and future body ideals, and disordered eating among preadolescent girls: A longitudinal panel study. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 35(2), 146-156.

Harrison, K. & Hefner, V. (2011). Media, body image, and eating disorders. In S. Calvert & B. J. Wilson (Eds.), The Handbook of Children, Media, and Development (pp. 381-406). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Harrison, K., Taylor, L.D., & Marske, A. L., (2006). Women’s and men’s eating behavior in response to exposure to thin-ideal media images and text. Communication Research, 33(6), 507-529.

Jenkins, H., Purushmotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K., & Robison, A. J. (2009). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Kilbourne, J. (2010). Killing us softly 4: Advertising’s image of women [video]

Lacroix, C. (2004). Images of animated others: The orientalization of Disney’s cartoon heroines from The Little Mermaid to The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Popular Communication, 2(4), 213-229.

Martin, C. L., Ruble, D. N., & Szkrybalo, J. (2002). Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 903-933.

Mulvey, L. (1989). Visual and other pleasures. London: Macmillan.

Norris, M. L., Boydell, K. M., Pinhas, L., & Katzman, D. K. (2006). Ana and the Internet: A review of pro-anorexia websites. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39, 443–447.

Rowsell, J., & Pahl, K. (2007). Sedimented identities in texts: Instances of practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 42(3), 388-404.

Ryan, E. L., & Hovis, S. (2015). Collaborative starvation and the invisible podium: Using twitter as a “how to” guide to spread eating disorders. Under review.

Sands, E. R., & Wardle, J. (2003). Internalization of idea body shapes in 9-12-year old girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33, 193-204.

Sax, L. (2010). Why are so many girls cutting themselves? Psychology Today. Available online.

Stice, E., Spangler, D., & Agras, W. S., (2001). Exposure to media-portrayed thin-ideal images adversely affects vulnerable girls: A longitudinal experiment. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 20(3), 270-288.

Stice, E., Schupak-Neuberg, E., Shaw, H. E., & Stein, R. L. (1994). Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: An examination of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 836-840

Stone, K. F. (1975). Things Walt Disney never told us. Journal of American Folklore, 88, 42-49.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Cachelin, F. M. (1999). Body image concerns and disordered eating in adolescent girls: Risk and protective factors. In N. G. Johnson & M. C. Roberts (Eds.), Beyond appearance: A new look at adolescent girls (pp. 85-108). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Sulls, J., & Wheeler, L. (2012). Social comparison theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology (pp. 460-482). London: Sage.

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Wade, T. D., Keski-Rahkonen, A., & Hudson, J. (2011). Epidemiology of eating disorders. In M. Tsuang & M. Tohen (Eds.), Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology (3rd ed.) (pp. 343-360). New York: Wiley.

Wohlwend, K. E. (2009). Damsels in discourse: Girls consuming and producing identity texts through Disney princess play. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(1), 57-83.

Image credits

Jennie Park, “Beast and Princesses,” Flickr, 2012.