Few toys have as enduring and beloved a presence in popular culture as the LEGO brick. Named “Toy of the Century” twice, subject of a widely lauded 2014 feature film (The LEGO Movie), and surpassing Mattel in the same year as the largest toy company (by sales) in the world, LEGO’s near-ubiquity has bolstered the image of the plastic bricks as an icon of design and a pillar of modern childhood 1 . In the context of the company’s massive commercial successes, two concurrent artist-driven LEGO exhibition projects–differing from one another in their aims, aesthetic presentations, and contexts of display, but united through the choice of a popular plaything as an expressive medium–provide an intriguing opportunity to explore the complex attitudes toward play and playthings that run deep in American culture.

The Art of the Brick

Self-described LEGO artist Nathan Sawaya’s The Art of the Brick, on view from February 7 to October 4, 2015 at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, presented a series of original figurative sculptures built from the plastic bricks, as well as detailed replicas of well-known works of art. Meanwhile, Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson’s The collectivity project, hosted at the High Line Park in New York (May 29-October 12, 2015), was a participatory installation of all-white LEGO bricks that invited viewers to contemplate notions of community, architecture, and urbanism. I contend that the enthusiastic reception that each project received stems in part from the ways in which they mirror some of the key marketing narratives LEGO has developed around the bricks. The prominent place LEGO occupies in the popular imagination, and specifically its associations with a discourse of creativity, provide both Sawaya and Eliasson a sturdy cultural foundation upon which to build their respective creations.

Nathan Sawaya (born 1973) is a Manhattan-based artist who works entirely in the medium of LEGO bricks. His personal background represents a sort of rags-to-riches story for the era of the creative class: after working for years as a corporate lawyer and spending evenings playing with his collection of LEGO–a favorite pastime since his childhood years–to unwind, he began to receive attention for his creations and decided to attempt making a living from them. After he built up a resume of commissions for private clients, Sawaya’s solo exhibition The Art of the Brick first opened in 2007 at the Lancaster Museum of Art in Pennsylvania. Since then, it has seen more than seventy iterations in eleven countries, reaching an audience in the millions. 2

The Art of the Brick opens with a short film introducing the exhibition. In addition to clips of Sawaya describing his background, how he came to his current career, and what viewers can expect to see in the exhibition, the video seems designed to prime the exhibition visitor’s receptivity to the show: it features a rapid collage of clips of Sawaya’s exposure in high-profile media, footage of obviously enthusiastic children and adults viewing the works, and a rapid sequence of the far-flung locales to which the exhibition has traveled. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the video seems to be particularly kid-focused in the register of Sawaya’s narration, although the main message he imparts is one that LEGO itself has consistently directed at both child and adult audiences: creativity is paramount, and the LEGO brick is an ideal building block for achieving it. 3

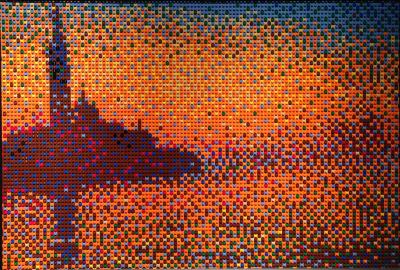

The first two galleries of the exhibition, as installed at the Franklin Institute, hold Sawaya’s LEGO renderings of famous artworks from history, beginning with a “paintings” gallery and moving on to a sculpture court. Sawaya’s selection of works hews, for the most part, to a fairly conservative art-historical canon (nineteenth-century Western painters dominate), although a few surprising choices–a Benin bronze mask, for example, or the British Museum’s famous turquoise-clad double-headed serpent figure from Mexico–add welcome notes of diversity. The galleries that follow contain Sawaya’s original works, organized under broad themes like “Metamorphosis” and “The Human Condition.” The works range from the heavy-handed and literal (e.g., a giant yellow pencil meant to evoke the power of artistic imagination, or flat pixelated portraits of Sawaya’s partner Courtney) to the more evocative and even unsettling (surrealistic androgynous human figures or Sawaya’s mask-like self-portrait rendered at many times life-size).

Previous commentators on Sawaya’s work have differed widely in their views, from firmly declaring The Art of the Brick “not art” to a more even-toned assessment that while some of the pieces are trite in conception or awkward in execution, many others impart a sense of the craft required in their creation and an attractive sense of playfulness. 4 And indeed, Sawaya’s facility at rendering complex forms in this perforce pixelated manner is impressive, and his playful experiments with scale and color make the exhibition’s galleries visually lively.

Both Sawaya himself and commentators on his work have made sure to note that he uses, with extremely few exceptions, only the most basic shapes in the vocabulary of LEGO components: rectangular bricks, beams, and plates. The diverse elements with slopes, angles, or curves, or any of the representational pieces like wheels or windshields, are noticeably absent from Sawaya’s works. The artist casts the self-imposed restriction in homage to the material itself, a paean to the elemental shape of the basic LEGO brick. But it also seems to derive from the long-running belief among many adults that the quality of abstraction in playthings leaves more to children’s imagination, fostering their creativity to a greater degree than overly realistic toys. 5 The lamentations of many adult LEGO fans that the company’s contemporary designs are too driven by novelty, narrative, or genre and pop-culture associations contain echoes of this same discourse, prizing a blocky image of “classic” LEGO. In the context of the grown-up suspicions toward novelty and representation in playthings, Sawaya’s reductive material vocabulary reads as a part of his attempt to stake a claim for LEGO as a “serious” artistic medium and distance his work from the more market-driven design of the company’s recent products.

The act of artistic mimesis in The Art of the Brick’s opening galleries, though, is a recurrent thread within LEGO’s own history. Many of the large, complex constructions the company has mobilized in its marketing and design efforts have relied on the playful recreation of real-world entities–people, vehicles, buildings, or whole towns. Since the first LEGOLAND park opened at the company’s Denmark headquarters in 1968, LEGO has used the replication of cultural icons from around the world to promote the toy; in the 1980s and early 1990s, the company also mounted multiple touring shows of elaborate LEGO displays, focused on themes like safaris, space travel, or history. These extremely popular productions relied on the ludic pleasures of miniaturization and the playful staging of narrative vignettes within the larger constructed scenes. 6

The Art of the Brick draws upon these ample precedents in the public exhibition of LEGO, but where these previous examples were fairly transparent promotions for the toy company, Sawaya asks the viewer to consider the works in The Art of the Brick as the products of artistic authorship and individual creativity. This is most successful when Sawaya resists the urge to hand-hold viewers and allows a work’s expressive capabilities to stand on its own. Many of the labels accompanying individual works or quotations by the artist rendered on the gallery walls, however, seem to indicate a degree of mistrust in the works’ ability to communicate; large quotations on the wall attributed to Sawaya instruct visitors that “This exhibition engages the child in all of us while at the same time highlighting sophisticated and complex concepts” or that “Art nurtures the brain. Whether made from clay, paint, wood, or a modern-day toy.” The irony of these messages, of course–rooted as they are in tactility and the idea of open-ended play–is that Sawaya’s sculptures are secured to walls and platforms, surrounded by continuous exhortations against touch.

The Collectivity Project

Olafur Eliasson’s The Collectivity Project installation, mounted from May 29 to October 12, 2015 on New York’s High Line Park, in some ways represents a perfect foil to Sawaya’s painstakingly constructed, statically installed works. Part of Panorama, a group exhibition of sculptures and installations from eleven contemporary artists, Eliasson’s contribution to the project is the most participatory of the diverse works installed on the elevated park. The Collectivity Project consists of two tons of white LEGO bricks–again with a limited selection of forms, skewing toward the basic bricks and plates–forming the imagined towers and boulevards of a miniature city. The work explicitly invites passersby to alter the construction with their own contributions, changing what others have built and in the process meditating (or so one hopes) on the collective nature of architecture, cities, and place-making. Over the duration of the installation, the built forms continually grow and subside in a messy process of what Eliasson admiringly characterizes as “entropy.”

Eliasson, born in 1967 in Copenhagen and trained at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, has become well-known for his large-scale installations that mobilize unconventional artistic materials–water, air, or light–like The weather project (2003) in the turbine hall of London’s Tate Modern or New York City’s Waterfalls in 2008. With his studio based in Berlin, Eliasson has mounted a few previous iterations of The collectivity project, in Tirana, Albania (2005), Oslo (2006), and Copenhagen (2008). 7 New York’s version–the first in the United States–offers a twist on the cooperative building experience: the initial LEGO constructions built for the opening of the installation were designed by several prominent architectural firms, each of which has played some part in the recent flowering of new architecture surrounding the High Line itself: BIG, David M. Schwarz Architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, James Corner Field Operations, OMA New York, Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Robert A.M. Stern Architects, Seldorf Architects, SHoP, and Steven Holl Architects all contributed a “visionary structure” to The collectivity project, ranging from fairly conventional skyscraper forms to a tree-like work, an unusually organic approach to the rectilinear LEGO bricks. 8

This star-studded list of participants notwithstanding, the rhetoric of The collectivity project indeed underscores the lengthy relationship between building toys and grown-up notions of architecture and engineering. From early mass-produced toys of the nineteenth century like the German Anker stone blocks to twentieth century favorites like Lincoln Logs and K’NEX, construction toys have long embodied the educative and aspirational values adults have projected onto playthings. 9 While LEGO has spun a marketing narrative for its bricks as a limitless system for play and invention, it too has deep roots in architecture, with the building suggestions on its earliest packaging and advertisements heavily weighted toward architectural subject matter.

In 1955, the company made an attempt to coordinate the sets of bricks into a coherent system for marketing and sale, reorganizing them around a “Town Plan” conceit that resonated with postwar functionalist architecture in Denmark. 10 The collectivity project’s all-white aesthetic parallels the mostly-white sets of the Town Plan era, and its explicit focus on urbanism-through-collaborative-play hews closely to the images of children playing together quietly in LEGO marketing of that time. It also strongly evokes the efforts of European educators and architects to mobilize children’s play for societal benefits, like Danish landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen’s 1939 articulation of the “junk playground” concept (which came to be known as “adventure playgrounds” in postwar Britain), or British architects Alison and Peter Smithson’s argument–in critique of postwar modernist planning methods–that children’s play could provide a new approach to urban design. 11 The collectivity project has shades of these efforts to understand and use playful building within a larger utopian mission, particularly their overtones of “regeneration” in the urban landscape and the therapeutic value of cooperative play, but Eliasson’s use of the miniature medium of LEGO doesn’t carry quite the same radical weight as these precedents.

LEGO bricks themselves were tethered more explicitly to the architectural profession in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when a number of architecture exhibitions took up LEGO bricks as their medium of representation. Architectuur in Lego (Rotterdam Kunststichting, 1984), “L’architecture est un jeu…magnifique”: 30 œuvres architecturales en briques LEGO (Centre Pompidou, 1986), and The gate of the present (Deutsches Architekturmuseum, 1992) each commissioned a number of architectural firms to design and build forms that responded to contemporary theory and debates within the profession. Firmly ensconced within the postmodernist discourse, the entries used the plastic bricks to great effect, emphasizing bold color and pattern and playfully remixing historical forms. 12 Reijn van der Lugt and Albert Roskam, the organizers of Architectuur in LEGO, allude to the unusual juxtaposition of avant-garde architecture and a children’s plaything in their introductory essay to the exhibition catalog: “The use of LEGO materials gives the design an ironic, perhaps absurd value. Although the exhibition is not primarily for the average Lego user, it will hopefully still reach a larger audience than is especially interested in architecture.” 13 And indeed, most of these exhibitions toured to institutions beyond their initial venues, promoting both a playful vision of the architectural profession and the architectural aspirations of the plastic bricks.

While these exhibitions deployed LEGO as a modeling medium with a resounding wink (alongside Roskam and van der Lugt’s purported attempt to democratize the theories of avant-garde architecture), that sense of postmodernist irony is completely absent from Eliasson’s The collectivity project. By inviting the viewers of the installation to participate in building a shared vision of a future city, the artist inverts the didactic premise of these earlier architectural LEGO projects, while at the same time reinforcing the ideas of universality and urban utopianism that have characterized LEGO’s own marketing over the company’s history.

LEGO on Display

A 1991 New York Times article on LEGOLAND captured the appeal of the park and the virtuosity of its plastic constructions: “Anyone who has ever watched a child play with Legos–as well as anyone who hasn’t–will be delighted with what the Danes have created…even the visitor who knows nothing of Lego can’t help being amazed at the extraordinary detail.” 14 This sort of universalizing attraction seems equally evident in both The Art of the Brick and The collectivity project. A key difference between the two projects, though, is the evident relationship between artist and material. The collectivity project presents as a matter of course that LEGO bricks should be the vehicle for a public installation of playful building, while Sawaya continually reminds viewers of his fondness for the toys, and that his choice of medium renders him a “pioneer”.

In rejecting profusion of colors that has come to characterize LEGO products and placing the emphasis squarely on collaborative building, Eliasson’s installation attenuates the narrative of triumphant individual creativity that LEGO has offered in recent decades–and how different a form of urbanism it offers than the company’s own city-themed products! 15 However, it also relies heavily on the assumption of the bricks’ “universal play value,” a marketing line LEGO has used since the early years of the toy. Sawaya’s work similarly finds close parallels in many of LEGO’s own efforts to draw a direct link between brick-play and creativity. The personal story he offers represents a kind of paradigm for finding a creative life through LEGO play, while the exhibition itself claims the abstract modular brick as a supremely flexible medium of representation. (Of course, both artists have a degree of access to their materials that most customers of LEGO could never themselves enjoy, but perhaps this only adds to the attraction for devoted fans of the toy.)

This conjunction of what might otherwise be differing artistic and corporate aims allows us to rethink the typical dichotomy drawn between popular and high culture in the arts. Far from suffering a lack of attention or interest thanks to their close ties to a major corporate entity, both projects have achieved their popular success precisely because the artists are able to offer visitors a vision of what many of them already believe: the building with LEGO bricks is an inherently creative act, and that the playthings merely await the transformative power of the imagination. While LEGO–counter to Sawaya’s claims–has not been readily embraced by the institutions and critics of mainstream contemporary art, the reception of The Art of the Brick and The collectivity project indicate that a broad segment of the public will nevertheless enthusiastically engage with such projects. Together, they represent a fascinating case study in how a widely beloved plaything can take on multivalent meanings outside the context of the playroom–as well as illuminating LEGO’s important place in popular culture.

Footnotes

- For a typical example of the breathless business-press coverage of LEGO, see Jens Hansegard, “Oh, Snap! Lego’s Sales Surpass Mattell,” Wall Street Journal, September 4, 2014 (accessed September 29, 2015.

- For Sawaya’s biography as well as listings of the tour itinerary for The Art of the Brick, see the artist’s official site, (http://www.brickartist.com/). Accessed October 4, 2015.

- Sawaya’s claim to be the first artist to “take LEGO into the art world” is, however, not true–German artists Heinz Kleine-Klopries (born 1949) and Wolfgang Hahn (born 1953) were both making sculptural works incorporating the plastic bricks in the 1980s. See Henry Wienceck, The World of LEGO Toys (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), 115-16 and 121-22.

- A less-sanguine review appears in Jay Merrick, “Sculptor defends Lego show ‘the Art of the Brick’,” The Independent, September 26, 2014 (accessed September 27, 2015). The more positive end of the spectrum is exemplified by Edward Rothstein, “A Vision That’s Not Quite a Snap,” New York Times, June 13, 2013 (accessed September 27, 2015).

- See Amy F. Ogata, Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), especially chapters 1 and 2.

- For LEGOLAND’s history, see Wiencek, World of LEGO Toys, or the “Legoland” section in the excellent Jim Hughes, Brick Fetish, online publication, 2010 (accessed October 3, 2015). Documentation of the LEGO World Shows is scattered across the Internet; one of the most comprehensive collections of material is Richard Topelen’s collection at “[LEGO World Shows](http://www.miniland.nl/lego world shows/index.htm),” Miniland Online (Dutch), n.d. (accessed October 3, 2015).

- Studio Olafur Eliasson, “The collectivity project,” 2005-2015 (accessed September 29, 2015).

- Commentators have eagerly drawn comparisons between the installation and the fervor construction at the Hudson Yards near the High Line. See, e.g., Kriston Capps, “Tear Down Buildings by Famous Architects on the High Line,” CityLab (blog), June 4, 2015 (accessed September 30, 2015).

- The Canadian Centre for Architecture has published several illuminating catalogs on their collections of architectural toys that explore this idea in nuanced detail. See, especially, Alice T. Friedman, Maisons de rêve, maisons jouets/Dream houses, toy homes (Montreal: Centre Canadien d’Architecture, 1995) and Architecture Pontentielle: Jeux de Construction de la Collection du CCA / Potential Architecture: Construction Toys from the CCA Collection (Montreal: Centre Canadien d’Architecture, 1991).

- One of the most comprehensive accounts of this shift in LEGO’s production and marketing is found in Jim Hughes, “System i Leg,” Fetish, online publication, 2010 (accessed October 3, 2015).

- For adventure playground, see Roy Kozlovsky, “Adventure Playgrounds and Postwar Reconstruction,” in Marta Gutman and Ning de Coninck-Smith, eds., Designing Modern Childhoods: History, Space, and the Material Culture of Children (New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press, 2008), 171-90.On the Smithsons, see Juliet Kinchin, “Reclaiming the City: Children and the New Urbanism,” in Juliet Kinchin and Aidan O’Connor, eds., *Century of the Child: Growing by Design 1900-2000 (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2012), 161-3.

- See Reijn van der Lugt and Albert Roskam, Architectuur in Lego (Rotterdam: Rotterdamse Kunststichting, 1984); Reijn van der Lugt, Albert Roskam, and Susanne Korsager, “L’architecture est un jeu…magnifique”: 30 œuvres architecturales en briques LEGO (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou; Billund, Denmark: LEGO Group, 1986); and Deutsches Architekturmuseum and LEGO Group, The gate of the present: 25 contemporary LEGO gates with a historical introduction (Rotterdam: Stichting Kunstprojecten; Billund, Denmark: LEGO Group 1992).’

- “Het gebruik van legomateriaal geeft aan de ontwerpen een ironische, wellicht absurdistische meerwaarde. Hoewel de tentoonstelling niet in de eerste plaats voor de gemiddelde legogebruiker gemaakt is, zal zij hopelijk toch een groter publiek bereiken dan de vooral in architectuur geinteresseerden.” In van der Lugt and Roskam, Architectuur in Lego, 1.

- Barbara Kreiger, “All the World’s a Lego At a Park in Denmark,” New York Times, June 16, 1991.

- For a pointed critique of LEGO’s form of urbanism, see Alexandra Lange, “Living in LEGO City,” Print, May 16, 2012 (accessed October 5, 2015). It is also interesting to consider a LEGO product like the 2013 Architecture Studio in juxtaposition with Eliasson’s The collectivity project; the set shares the all-white aesthetic and architectural focus of the installation, but its smaller scale and its high price point distance it considerably from Eliasson’s collective vision and utopian aspirations; see Oliver Wainwright, “Could LEGO Architecture Studio actually be used for architects?,” The Guardian, August 6, 2015 (accessed October 5, 2015).