“FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD” read the front page of The Daily News on October 30th, 1975. Throughout the decade, the city’ economy was in a prolonged nosedive, burdened by the weight of a manufacturing decline, the flight of the white middle class to the suburbs, and massive debt taken on to shore-up these losses. 1 Hurtling downwards, the city’ Mayor Abraham Beame and New York’s Governor Hugh Carey sought federal help from President Gerald Ford, only to have the city’ impending crash sidelined given the failing state of the entire country’ economy.

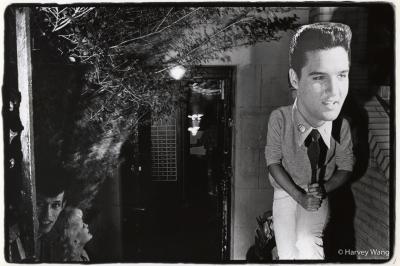

At the turn of the new decade, the city’ economy had yet to pull up. Entire downtown city blocks were vacant with buildings abandoned and crumbling. At night, on the nearly desolate streets, functioning street lights were a rarity and only few lights from occupied apartments provided further illumination. Despite the nearly opaque nighttime cityscape and its rather grim conditions, revelers stirred. At 57 St. Marks Place, nestled between broken, boarded-up townhouses, was the Holy Cross Polish National Church, which housed the newest hot-spot in its basement: Club 57. On a particularly sticky August evening in 1980, sweaty people dressed as Elvis and Priscilla Presley poured out of the church’ dim cellar space, peppering the otherwise deserted street with reflective slick pompadours and sparkling sequins. 2 The rush of people flooding the street was precipitated by the club’ air conditioner spontaneously bursting into flames, short circuited by club-goers pouring beer on it while it struggled to cool a hundred dancing Elvis and Priscilla impersonators. The arriving firetruck was overrun with partygoers hanging off of its ladders and posing with its hoses. To cool the chaos on the street, angry Polish residents, teetering out of their neighboring windows, began to throw buckets of bathwater at the partygoers. 3

While this scene is vivid — serving to picture the club’s atmosphere and the energy of its participants — it might not initially seem to be qualified as “performance art.” Ann Magnuson, the manager of the club, along with other members, would often organize themed “shows” (Elvis Memorial Night, Prom, mini golf, etc.), as a unifying foundation for events and performances throughout the evening. 4 With all attendees in costume and participating collectively — whether on stage or in the audience — Elvis Memorial Night evidences one of the defining characteristics of nightclub performance: performers and audiences were one and the same. Collaboration was the pioneering force behind this newfound category of nightly entertainment, what some called an “envirotheque; — an environmental discotheque.” 5 But Club 57 was only one of many such venues, with the community formed through performance expanding well beyond its basement space.

In the few years between 1978 and 1985, over nine new nightclub-performance venues opened in the roughly twelve square blocks comprising the East Village and the Lower East Side, providing nightly entertainment for and by a diverse community of young artists. These included Club 57, The Pyramid Club, The Limbo Lounge, 8BC, Darinka, Chandelier, King Tut’ Wah Wah Hut, and The WOW Café, among others. 6 Attempting to convey the flurry of artistic activity, critics at the time mythologized downtown as the “Elysian fields” the scene as “phenomenal” spoke of its “aura” and “mystical vitality” but in large part neglected any nuanced understanding of the political, economic, and social forces at play in its construction, beyond citing record numbers of art school graduates and cheap rents. 7 Later critical attention on the downtown art scene in the 1980s has tended to focus on the explosion of storefront galleries, neo-expressionist painting, graffiti art, alternative spaces, punk and new wave music, but there has been scant analysis of performance’ central role in the development of the scene and its market, let alone of the works themselves. By the late 1970s, however, it became increasingly evident that performance was the connective glue of the downtown community. Nightclub performances, in particular, were crucial in the construction of this community, creating a marketplace for the production and consumption of new cultural content. Entertainment — characterized by pleasurable symbolic and economic exchanges between performer and audience — emerged as a means to build and cater to new audiences. In the words of Jim Fourratt, the manager of the club Hurrah and subsequent owner of the club Danceteria, “If you don’t have pleasure you don’t have community.” 8

My assessment of the market for performance is positioned against the two dominant and polarized interpretations of this work — first is the argument that this community of artists was subversive, and second, that they were sell-outs. The “subversive” argument, most prominently propagated by Marvin Taylor in The Downtown Book and by performance art historian RoseLee Goldberg, among others, reinforces the popular understanding that artists of the 1980s were fatigued by the “art establishment,” did not conform to the desire for economic capital, and often, in the spirit of irony, appropriated business structures only to subvert them. 9 This argument is further characterized by the belief that downtown performances parodied the market, accruing symbolic capital within a “restricted field” — a term proffered by Pierre Bourdieu, for whom the “restricted field” of cultural production is opposed to mass cultural production. 10 This position continues with the argument that by the mid-1980s the cultural capital amassed in the ‘restricted field’ was usurped by real capital, citing the evidence of the rising art market and acts characterized as “crossover” (crossing over into popular culture) like that of Laurie Anderson, Ann Magnuson, Eric Bogosian, and David Byrne. Following Taylor’ argument, Elizabeth Currid affirms in her book The Warhol Economy, that downtown artists would produce “art for art’s sake” — what Bourdieu would call “symbolic capital” — “with no real regard for economic reward.” 11 These arguments, smitten with subversion, disregard the blatant economy of punk and the nightlife scene — refusing to examine the particularities of exchange — resting too strongly on the anti-capitalist sentiments espoused by the artists themselves.

The “sell-out” argument was publicized by many critics and artists working during the time, including the critic Carlo McCormick, as well as the art historians Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan. This argument maintains that the work is unabashedly complicit with big capital — fueled by a desire for fame — and therefore, with the gentrification of downtown. 12 Both the subversive and sell-out views, however, leave little room for understanding the agency of the performer and performance as a medium. Certainly, these performers accrued symbolic, cultural capital; however, they were never operating within a “restricted field,” but rather consciously maneuvering to create a unique market for performance art the likes of which had never been seen before. This community built their own supply and demand, based on the production, sale, and consumption of the affective, immaterial labor of performance. Indeed, one can neither subvert nor sell-out in the market one produces, sells, and consumes.

While these two arguments are specific to the downtown art scene in the 1980s, a more overarching and pervasive understanding of performance prevails, stemming from artists” deployment of the medium during the 1960s. With a postwar art market largely dominated by the sale of objects — most significantly, large-scale modernist sculpture and Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s and Pop paintings and sculpture in the 1960s — performance emerged during the 1960s as a rebellious alternative, seen as distinctly market-subverting by virtue of its ephemerality. This persistent understanding of performance as inherently subversive fails to account for the profoundly changed character of the market in the 1970s. Indeed, the art market is typically considered a goods-based market despite larger economic shifts away from the production of goods and commodities. The literature discussing the art-market boom taking place downtown during the 1980s continually cites the growth of store-front galleries and the market ascension of painters Julian Schnabel, Jean-Michele Basquiat, Kenny Scharf, and Keith Haring, among others, who produced goods for sale — either high end (Schnabel) or affordable multiples (Haring). However, if we assess performance alongside the development of a market capitalizing on affective, immaterial labor and services — rather than goods — then we have a model for understanding performance’s own economy and boom during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Performance thrived in the for-profit spaces of downtown nightclubs and grew distinct from the burgeoning non-profit avant-garde theater world of PS.122, La Mama, and others.

I argue that between the emergence of punk in the late 1970s and the art market boom of the 1980s, performance art found a way to create and profit from a market economy, despite the medium’ ephemerality and the city’ economic downturn. I contend the growth of performance in the 1980s owes its success to neither total subversion nor selling-out, but rather to the entrepreneurial creation of what I call a “market-community,” a community constituted by practices of production and consumption, and emblematic of the larger economic shift towards affective and immaterial labor in a post-Fordist service economy. 13 The term “market-community” brings together two words often thought of as antithetical — exacerbated by the characterization of this generation of artists as averse to the institutionalized “uptown” art market and who are often understood as forming the downtown community as a utopic rebuttal to that market. My creation and use of the term seeks not to discredit these views or accomplishments, but rather, to assert that there is another way to understand this moment: recognizing that there was a successful, DIY market for performance art that was community-generated and began in nightclubs.

Tim Lawrence, in his recently published book, Life and Death on the New York Dancefloor: 1980-1983, characterizes the impact of the recession on the 1980s as follows: “Sages read the national mood and announced that it called for belt-tightening, hard work, and a reassertion of traditional values. It had become, in short, a bad time to discuss the pleasures of the dance floor with one’s bank manager.” 14 This market for performance, as it began in nightclubs, may not have come anywhere close to the booming revenues amassed by galleries during the decade, nor filled the community’ constituent’ pockets with wads full of cash, but the dance-floor was not entirely cut off from a conversation with the market. Nicholas Ridout and Rebecca Schneider, in their introduction to a special issue in The Drama Review on “Precarity and Performance” reminds us:

At one time, claims for resistance to commodity capitalism were addressed through the idea that performance does not offer an object for sale. What of the performing body in an economy where the laboring body, and its production of affect, is the new commodity du jour? Marx already gives us the immaterial commodity that is labor itself. Can we think about this through the labor of performance? 15

It is precisely through the idea of performance as labor— but also pleasure — that this paper establishes ground.

To highlight the explosion of performance in the 1980s and the creation of this marketplace for performance, it is necessary to briefly set it apart from performance in the preceding decade. The art world during the 1970s was not located in the East Village or the Lower East Side, as it was in the 1980s, but was instead centered in SoHo. The dwindling manufacturing industry abandoned the area, leaving large industrial spaces and lofts empty and their vacancies were often filled by artists. These lofts were repurposed as living and studio spaces, and, in some cases, became performance venues, leading to the advent of many “alternative spaces”like 98 Greene, the 112 Greene Street Workshop, Robert Wilson’s Byrd Hoffman School for Byrds located at 147 Spring Street, and The Kitchen at 59 Wooster, among many others.

Performance in downtown New York during the 1970s was relatively hermetic, with small crowds comprised of mostly friends or people “in the know” — for example, Jack Smith’s midnight to 5AM performances at his Green Street loft known as the Plaster Foundation; Jared Bark”s LIGHTS on/off performed at The Clocktower, located on the top floor of the New York Life Insurance Building near Canal Street; performances that took place for unwitting audiences, with artists like Stuart Sherman performing his humble manipulations of objects, ironically titled “spectacles” to passers-by on the street. While it is difficult to uniformly characterize these performances, the general sentiment held by these artists of the 1970s and even into the 1980s was one of anti-establishment, and anti-institution, distancing from the uptown art market — it was, in the words of J. Hoberman, “Performance for its own sake.” 16 Eventually priced out of SoHo, pioneering artists, or — to again use the words of Jim Fourrat, these “cultural instigators” — shifted to the Lower East Side and the East Village, making the area the newest locus of artistic activity. There, they created their own market in the clubs.

The work presented in nightclubs during the late 1970s and 1980s was characteristically entertaining (often prop-filled, strange, and hilarious) developing in tandem with this new market-community; the downtown performance community was built on pleasurable symbolic and economic exchanges between performer and audience. For example, in 1978, Ann Magnuson curated the New Wave Vaudeville show at Irving Plaza, where everyone who wanted to perform got five-minutes or they were yanked from the stage. Dressed as a Sci-fi Cleopatra, Magnuson introduced the audience to the show with quite a build-up, seductively proclaiming, “Its newer than new, it’s you-er than you, it&rdsquo;s now-er than now, and it’ wow-er than wow.” The showcase featured the art band Come-On entering the stage in suits and attaché cases, which popped open to reveal foam guitars that the band began to faux-play as the instrument’ necks flopped around. During the same night, Klaus Nomi made his first stage appearance, robotically walking up to the microphone, located center stage, dressed in Martian-drag singing the aria Mon cœur s’ouvre à ta voix (“My heart opens to your voice”) from Camille Saint-Saëns” 1877 opera Samson and Dalila, his hallucinogenic presence heightened by a cloud of detonated smoke-bombs. In fact, the New Wave Vaudeville show could be understood as a kind of incubator for the explosion of performance seen in the clubs scattered around the East Village in the 1980s.

As such, the club 8BC presented over 666 performances in its first year, since their opening night on Halloween 1983. They used a three-set format each night, with the first set beginning at 9PM, and the last at 2AM. Any given evening offered a mix of cabaret, theatre, dance, and music. Tom Murrin, the Alien Comic, performed a monologue in a layer of seven costumes and would systematically yet fervently rip a layer off, one at a time, while clamoring on about nuclear war, gentrification, and Reagan. Ethyl Eichelberger, the renowned drag performer, veteran of Broadway, and the Ridiculous Theatre Company, transformed the club into the Moulin Rouge, premiering the work Toulouse Women or Moulin Rage, which involved line-kicking, playing the accordion, and dialogues about unrequited love taking place backstage. Between intervals of performances, a DJ would spin mostly unreleased tracks from area bands who had yet to receive label contracts. As one club goer remarked, “8BC is a relativist’s fertile ground where the assumption is that everyone can benefit from everyone else’s work.” 17

At Club 57, artist Keith Haring regularly performed his poetry and curated art exhibitions like the Club 57 Invitational. At the Canal Zone party, painter and graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and artist, writer, and filmmaker, Michael Holman, met for the first time and immediately decided to form a band they would later call Gray. As Holman recounts, “In one night Jean and I meet for the first time, Freddy Brathwaite (Fab Five Freddy) and Jean meet for the first time, Jean meets Lee Quinones for the first time, the downtown scene and the graffiti scene meet for the first time, and Gray is started… in one night. That was typical. Shit like that happened all the time.” 18 They decided on the name Gray for the band, after Gray’s Anatomy, Basquiat’ favorite reference book, and premiered their sound at club Hurrah in 1979. Neither Holman nor Basquiat technically knew how to play an instrument, but that didn’t stop Holman from beating the drums, Basquiat from wailing on the clarinet or twiddling knobs on the Wasp synthesizer. 19 In an example of nightclub performance’ expansion beyond the confines of the club, Gray brought their aesthetic to elite gallerist Leo Castelli’ birthday party, where Basquiat played a shopping cart designed by Cooper Union student Peter Artin. The cart was outfitted with an industrial electric motor that drove a bent shaft, which caused the machine to make a loud clanging noise and thrash about rather dangerously. Holman recalled that when “Jean-Michel plugged it into a socket, this thing rattled around like hell was coming through the door.” 20

The artist David Wojnarowicz was hired as a busboy at the club Danceteria, and founded the band Three Teens Kill Four with two co-workers from the club, Brian Bitterick and Jesse Hultberg. Their first performance, which took place at the Danceteria staff party held at another downtown club called Tier Three, featured a cacophony of found-sounds played on cheap hand-held tape recorders, toy instruments, spoken word with layered vocals. These few examples serve to characterize the myriad kinds of performances taking place in these clubs, the range of artistic practices, and diversity that constituted the downtown performance community.

In terms of the market for downtown performance, the exchanges taking place trafficked in both symbolic and real capital. At some clubs, the performers — mostly the bands — were paid meagerly. But at most clubs, the performers were not directly compensated for their performances, instead, they took a percentage of the door admission price, which ran anywhere between $2 and $10 a head, and were often given a cut from the bar. Nightclubs encouraged performers to adopt an artist-entrepreneur model by financially rewarding the successful promotion of their acts. Upon seeing the success and support of such a market, and its ideological divergence from the “uptown” art market, more community members, club bartenders, and audience members decided to shift from the crowd to the stage, helping grow this community and market for performance. For example, noted performer Karen Finley, after graduating with an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, procured an NEA grant and moved to New York City, taking a job as a bartender at Danceteria. It was during her post as a bartender and witnessing nightly performances that she decided to take the stage herself. 21 As Charles Tarzian writes in the pages of The Drama Review’ special issue devoted to the East Village Clubs, these clubs get “… performers on stage and performers in the audience — (it is) an audience of peers.” 22 At the club 8BC, for example, when a band booked to play the final set of the night canceled at the last minute, the club pulled together a band from the audience members. Literally, the audience became the performers and the performers the audience, reinforcing the strength and success of this market-community. In assessing the forms of exchange taking place during these performances, it is clear that nightclubs serve as a foundational site for the building of the interactional, service economy — trading in the affective and immaterial labor of performance.

Moreover, this economy continued to grow and expand beyond the nightclub. It is towards the early to middle of the decade that we begin to see another shift in performance, this time towards the professionalization of performance artists with the leap in scale to spectacular, expensive, highly-produced multi-media events. For example, Laurie Anderson premiered United States at BAM in 1983, to a capacity crowd of 2,100 people, as part of BAM’s inaugural Next Wave Festival (ongoing), which sought to bring performance to larger audiences, and in doing so, signaled performance’s shift into the sphere of professionalized labor. With this passage into the realm of mass entertainment, performance artists became increasingly referred to as “the talent” and their productions often incorporated the latest multi-media technologies.

Beyond exploding outwards to larger venues and bigger crowds, many artists ended up migrating off the city’ grid and into televised space. Indeed, Laurie Anderson’s single “O Superman” not only reached the top of the music charts after its release in 1981, but also premiered on MTV during the channel’ inaugural year. No Wave Cinema, an underground filmmaking group, premiered experimental films in downtown performance clubs like the Mudd Club and Club 57, and many subsequently developed fictional TV shows on free-access cable networks. Glenn O’Brien’ TV Party, a public access show, operated from 1978-1982, recreating the nightclub atmosphere on cable, bringing the downtown brand of entertainment to a wider audience. Television was, in fact, the logical expansion of this economy of performance, no longer bound by a physical location, or physical interaction between performers and audience, but ultimately this divergence aided in the disintegration of downtown’s “market-community.” By 1988, the move to large-scale venues and onto television, the closing of many nightclubs, the toll of the AIDS epidemic, and the ramifications of Reagan’s policies all together started to dismantle the community that was started in the clubs, and built through performance.

To be sure, while this market-community was not the most profitable market, it existed nonetheless, providing the necessary groundwork for understanding the current fascination with the very profitable market for contemporary performance art. With the art market largely considered a goods-based economy, art history operates within this model. But by focusing on performance, I have reconsidered artistic production within the context of a service economy, arguing that performance in the 1980s is a market-generating medium predicated on affective social exchanges between audience and performer. This analysis of how downtown performance in the 1980s, as an entrepreneurial venture, created a “market-community,” also forms the necessary historical context for the contemporary fascination with selling performance art (for example, Tino Sehgal and Marina Abramović — two performance artists who have had blockbuster shows at two of the world’s most prominent institutions), which undoubtedly has its roots in the 1980s. Moreover, this focus on the economies created through performance may provide a particular methodology for assessing synthesized artistic practices — and that perhaps, there is never a bad time discuss the pleasures of the dance floor or the stage with one’ bank manager.

Footnotes

- Brian Tochterman states, “Since 1969 the city had lost nearly 500,000 jobs, and twice as many middle-class taxpayers had left New York in the decade prior. The city’ woes were indicative of broader trends, as the national economy foundered as a result of geopolitical conflict with countries in Southeast and Middle East Asia, deindustrialization, and the final transition to a postindustrial order at home.” Brian Tochterman, The Dying City: Postwar New York and the Ideology of Fear (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 1.

- According to the club’ calendar of events, the Elvis Memorial Night party occurred on Saturday, August 16th, from 10PM till close.

- This incident recalled in several accounts, most notably in Ann Magnuson, “Club 57” Artforum (October, 1999), accessed online on June 24th, 2017 https://www.artforum.com/inprint/issue=199908&id=840&show=activation. Scene recounted in Tim Lawrence, Life and Death on the New York Dancefloor 1980-1983 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 34; corroborated by interviews with several participants including Katy K and Alexa Hunter, October 30th, 2017.

- The theme party’s connection to performance art at this time can in fact be traced back to the Mudd Club. Bernard Gendron offers an interpretation of performance art-as-party at the Mudd Club, stating, “Seizing on the idea of doing performance art as retro trash, the B-52’ Fred Schneider organized a “theme party” with sixties beach movies in mind…Would-be performance artists eagerly picked up on this cue and produced theme parties on a regular basis, following in the highly conceptualized tradition of sixties be-ins and happenings. There were blond nights, monster parties, sixties revival parties, pajama parties…” Bernard Gendron, Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002), 300.

- Lawrence, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor: 1980-1983, 35.

- The Mudd Club (1978-1983), Danceteria (1979-1986), Pyramid Club (1979-ongoing), WOW Cafe (1980-ongoing), 8BC (1983-1985), Club 57 (1979-1983), Limbo Lounge (1980-1986), King Tut’ Wah Wah Hut (1980-1986), Darinka (1984-1986), Chandelier (1984-1986), The Peppermint Lounge (1980-1985), Palladium (1985-1997) and many more opened during this time and several closed before the end of the decade. While I generally classify these clubs under the same rubric of the “performance art nightclub” there are distinct differences between the spaces, which will be further examined throughout the chapter.

- See for example Grace Glueck, “A Gallery Scene That Pioneers in New Territories” New York Times, June 26, 1983; Michael Gross, “The Party Seems to be Over for Lower Manhattan Clubs” New York Times, October 26, 1985; Irving Sandler, “Tenth Street Then and Now” in The East Village Scene (Philadelphia: Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 1984); Kim Levin, “The Neo-Frontier” Village Voice, January 4, 1983; Carlo McCormick and Walker Robinson, “Report from the East Village” Art In America 72 (Summer 1984): 143-61; Elizabeth Currid, The Warhol Economy (Princeton, NJ; Princeton University Press, 2007); and countless other books and articles.

- Jim Fourratt, quote from the symposium convened at NYU on behalf of Tim Lawrence’s book, October 8, 2016.

- See Marvin Taylor (ed.), The Downtown Book (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 17-39; and also Robert Siegle, Suburban Ambush: Downtown Writing and the Fiction of Insurgency (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989).

- bid, in addition to RoseLee Goldberg, Performance Art from Futurism to the Present (New York: Harry N. Abrahams, 1988) and Goldberg, “Art After Hours: Downtown Performance” in The Downtown Book, 97-116. See also Uzi Parnes, “Pop Performance in East Village Clubs” The Drama Review, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Spring 1985): 5-16; Uzi Parnes, Pop Performance, Four Seminal Influences: The Work of Jack Smith, Tom Murrin—the Alien Comic, Ethyl Eichelberger, and the Split Britches Company (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1988). See also C Carr, On Edge: Performance Art at the Turn of the Century (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2008), where performance in the early 1980s is positioned as “post-television” responding to and parodying the culture of television.

- Currid, The Warhol Economy, 35.

- Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan, “The Fine Art of Gentrification”* October*, Vol. 31 (Winter, 1984): 91-111. Carlo McCormick, “Guide to East Village Artists: Supplement” in Neo-York: Report on a Phenomenon (Santa Barbara, CA: University of California Santa Barbara Art Museum, 1984).

- The entrepreneurial creation of this market also has a pragmatic dimension— as Carlo McCormick states, “we couldn’t get our shit together to write grants to become alternative spaces and that money was drying up anyways.” Interview, July 21, 2017. This conceptualization of the “market-community” is indebted to Miranda Joseph’s Against the Romance of Community, where she argues that community is “imbricated in capitalism” and that “communal subjectivity is constituted not by identity but rather through practices of production and consumption.” Miranda Joseph, Against the Romance of Community. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

- Lawrence, Life and Death on the New York Dancefloor, 1980-1983

- Nicholas Ridout and Rebecca Schneider, “Precarity and Performance: An Introduction” TDR 56, no. 4, (Winter, 2012): 6. Ridout and Schneider take their lead from recent Italian workerist theorists such as Paolo Virno, who writes, “The affinity between a pianist and a waiter, which Marx had foreseen, finds an unexpected confirmation in the epoch in which all wage labor has something in common with the ‘performing artist.” Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 68.

- The phrase is in fact the title of J. Hoberman’s essay in Jay Sanders (ed.), Rituals of Rented Island: Object Theater, Loft Performance, and the New Psychodrama—Manhattan 1970-1980S (New York: The Whitney Museum of American Art, 2013): 9.

- Charles Tarzian, “8BC: From Farmhouse to Cabaret” The Drama Review 29, no. 1, East Village Performance (Spring 1985): 112.

- Lawrence, Life and Death, 75.

- Ibid, 77.

- Ibid, 77.

- Interview with Gary Ray Bugarcic (founder and owner of Darinka), January 15, 2016.

- Tarzian, 122.