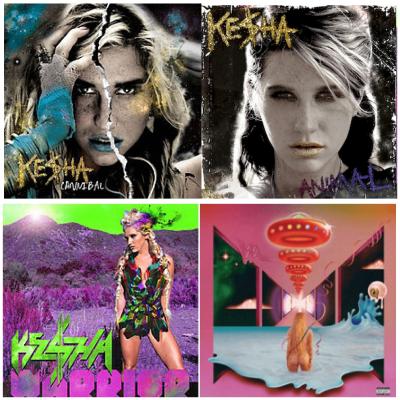

First Kesha was an Animal, then a Cannibal, then a Warrior, and now—in her fourth album—a Rainbow. The titles of her albums represent her thematic evolution as an artist and an icon; it’s difficult to imagine a rainbow eating a person or killing a White Walker. Central to her identity was that dollar sign, the most materialistic key on your keyboard. Almost like Athena, Kesha emerged fully formed in 2009 as a pop icon with unusual confidence in her sense of identity. Her song “Tik Tok” broke records as a digital single and immediately became a club staple. She flaunted hedonism, at once refreshing and ridiculous, a heavily auto-tuned diva who took the stage as though her hair was still unwashed from her club-cavorting the night before. Unfettered by sophistication or propriety, she showed up at the MTV European Music Awards that year wearing a ripped tank top and purple satin pants, looking, according to a website tellingly called Starcasm , like “that dangerous girl at the bar that [sic] doesn’t become a mistake until right around closing time.” This is a striking contrast to fellow attendee Miley Cyrus’ long white dress with cascading ruffles. 1 It looked like it would take a Silkwood shower to remove all the glitter from her skin. She is probably the only artist to both literalize and lyricize “pissing in the Dom Perignon.” 2

Unlike the other heavily marketed starlets who emerged in the late “aughts”—Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, and Lady Gaga—there was a menace about Kesha, something vampiric and decadent and uninhibited compared to Swift’s comfortable t-shirt ethos, Perry’s #woke buoyancy, and Gaga’s gender-bending kabuki. “Because really I’m just telling stories about the stupid shit I do,” she told Esquire in 2009, adding, “because I feel like my music stands for the ultimate statement of irreverence. ‘We don’t give a fuck / we don’t give a fuck…’” 3 If Miley Cyrus’ frantic twerk into sexual maturity seemed designed to make the marketing department at the Disney Channel collectively gasp, Kesha seemed like she just woke up that way. In the video for the exuberantly stupid “Tik Tok,” Kesha crawls out of a bathtub, brushes her teeth with Jack Daniels, and walks downstairs to ruin a suburban family’s breakfast just by appearing, unconcerned and mostly amused that she somehow ended up in an unfamiliar bathroom. 4 She collected teeth (“like, over a thousand”) from her fans and made them into a bra. She hosted naked body paint parties. 5 An early interview with Rolling Stone includes the sentence, “She burps, swears, talks about blow jobs, and, when she needs to take a leak, ducks behind a tree.” In the video from “Blow,” she kills unicorns and aging heartthrob James Van Der Beek. “Blow” begins with a Kesha cackle that gets my vote for the best thing to happen in recent popular music. 6 In that half-second, there’s a ridiculous, even dangerous vitality that is rare for music that gets FM radio rotation: the loud nihilism and energy and rejection of lyricism of EDM coupled with a knowing lack of self-consciousness, traditional glamour, and sophistication: “this place is gonna blow.”

And then something happened. Kesha not only started giving a fuck, she had to. She went through rehab for an eating disorder. She claimed wide varieties of abuse on the part of her producer, hit-making impresario and creepy lecher Dr. Luke. She went to court to plead for a breach in contract with Sony so she wouldn’t have to work with her abuser, and was continually rejected. Kesha kept losing appeals, and Dr. Luke went to Twitter to remind his detractors that the Duke Lacrosse team didn’t rape anybody even though everybody thought they did. 7 From 2013 on, after the release of her second album Warrior, Kesha’s life became a publicly documented hell. As she sang on “Emotional” (a bonus track for Rainbow) with a previously uncharacteristic vulnerability:

It started in November, I started losing my mind I ended up in rehab, I don’t want to cry But people can be so mean, and I don’t understand why And when they say I can’t sing, I just want to die. 8

She adds, “I’m supposed to be the girl that never does this / I’m supposed to be some party girl that stands for nothing.”

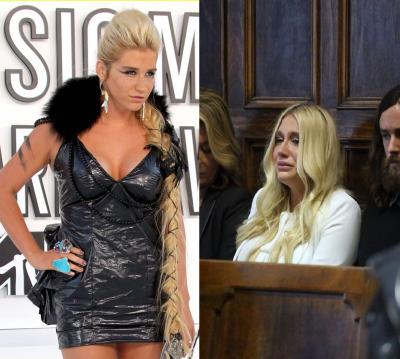

As judges told her that yes, she was sexually assaulted, just not sexually assaulted often enough to make her own music, her social media accounts documented her depression with a startling clarity and probing honesty that were the kind of core values that Kesha’s earlier music mostly made fun of. For most of us, she went from an icon who embraced shameless excess to a deeply forlorn and desperate figure incapable of doing anything other than expressing her hurt. Previously, a typical photograph of Kesha showed her sneering or laughing, bemused by her own fame. During these trials, the pictures were of Kesha crying somewhere in the vicinity of a courthouse.

Photo Credits: (Left) JustJared

(Right) NY Daily News

That transition was tough to square for those brought up on Kesha’s earlier beats (“Rat-a-tat-tat on your dum-dum drum / The beat’s so fat it’s gonna make me cum”), 9 who were entranced by the way she celebrated gothic futility and ignored everything else that exists. In a move equivalent to the son of Jor-El deciding he only wants to be Clark Kent in Superman II, she retired the dollar sign. Female pop stars have always channeled creative energy out of alternate identities (Sasha Fierce, Roman Zolanski , Art Nouveau, even Hannah Montana), and the fun thing about Kesha was a luminous lack of ambition to be that thoughtful about really anything. Further, Kesha-with-a-dollar-sign, the playfully nihilistic singer of “Sleazy,” seemed impossible to victimize. The seriousness of her life’s dark turn seemed to prohibit her from singing about “stupid shit” anymore. So, what would Rainbow be?

Kesha and her struggles, particularly surrounding the fraught production of Rainbow, are emblematic of what female artists (and not just contemporary pop stars) must face in their confrontations with both public expectations and male gatekeepers who work to control the production and reception of their work. This struggle contrasts with a front of defiant autonomy that artists like Kesha usually perform through their construction of a stage presence. In what follows, this article attends to the way Kesha deploys her music to address these tensions and attempt to reconcile them, which were emboldened in the months that followed the rise of the Me Too movement. Looking to writers and critics such as Rebecca Traister, Audre Lorde, and even the seventeenth-century poet Margaret Cavendish, this article considers the emotions that Kesha expresses in her music, the problems of identity and celebrity that emerge, and also the way she comes to terms with a salvation that is not resplendent or transcendent, but messy and personal.

Rainbow and the Bastards

Rainbow dropped in July 2017, just before the Me Too movement unleashed what Rebecca Traister calls”organic, mass, radical rage, exploding in unpredictable directions.” 10 In the years leading up to it, it’s not that Kesha lacked the skill or volume to marshal pathos, empathy, and action effectively, it’s that her narrative lacked the empowering context of Me Too’s righteous harmonizing of collective rage. Now that the floodgates are open, the activism is more incisively pointed at recent cases. This makes her reemergence with the triumph of Rainbow all the more exceptional, because it happened in the midst of Me Too rather than because of it. Rainbow did not become the anthem for the movement, and that’s reasonable; it’s too personal, elusive, and thematically incoherent. Kesha’s gestures toward justice and retribution are grounded in her need for emotional recovery, made vivid through a host of metaphors that help us understand who she was and what she’s working to become.

On the opening track of Rainbow, when she sings, “don’t let the bastards get you down,” we get the sense that the bastards have done just that. 11 The song is mostly acoustic, lacking the kind of crescendos and swagger that opened her earlier albums. The title track on her previous album, Warrior, declaims that she is just that, before adding:

We’re the ones who flirt with disaster On your ass, we’ll pounce like a panther Cut the bullshit out with a dagger With a dagger, with a dagger ‘Til we die, we all gonna stay young Shoot the lights out with a machine gun Think it’s time for a revolution, revolution, revolution. 12

Through such confrontational lyrics, Warrior marks a natural progression in terms of confidence, if not sound. Its triumphant, party-rap declares that she’s arrived as she basks in celebrity, announces she hasn’t changed, and threatens potential antagonists. So it is a striking contrast that Rainbow begins on such a subdued, defeated note:

I got too many people got left to prove wrong All those motherfuckers been too mean for too long And I’m so sick of crying, yeah Darling, what’s it for? I could fight forever, oh, but life’s too short Don’t let the bastards get you down. 13

With that “you,” she’s addressing the “we” in her earlier anthem, “We R Who We R,” those who were once “running this town just like a club,” but have been through a lot since 2010. 14 For the heavily produced and often auto-tuned Kesha, this acoustic song is particularly revealing, setting the tone for a new project that the name change also represented. If the Kesha of Cannibal got a hold of “Don’t let the bastards get you down,” she would have deployed it as part of an effort to shout the bastards down before “pounc[ing] like a panther” and mounting their heads. “But now that I’m famous, you’re up my anus,” she sings on Cannibal’s titular song, “Now I’m gonna eat you, fool.” 15 Those songs are about exuberant triumph: “I just can’t date a dude with a vag.” 16 That’s a notable, sad contrast to the admission that she’s “sick of crying.”

The phrase that Kesha repeats has its origin in Latin, Illegitimi non carbundum, where “illegitimi” actually translates as outlaws, and “carbundum” refers to silicon carbide, an abrasive compound that must be ground down into powder. Traditionally, this cliché has been invoked by hawkish military types, Barry Goldwater, and submarines, where it’s used to represent (respectively) peaceniks, civil rights activists, and other submarines. In Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Offred finds the Latin phrase carved into her bedroom closet and has to ask the amorous, effete, and impotent Commander (a bastard) what it means. 17 But in her opening gambit, Kesha reclaims it and drops the central chemical activity, which is fitting since her earlier songs often are about and are made to accompany acts of “grinding.” So instead of grind, the “bastards” will attempt to “get,” “wear,” “take,” and “screw.” It’s suggestive that she’s not using bastards to define her and her outcast “We R” army, but is instead reframing the illegitimate as those who have power, are abusing it, and are getting away with it. And this tone-setter, melancholy and soft rather than defiant, positions Kesha as being one of the people who might keep them from grinding.

The seemingly inane and grotesque line “Don’t be a little bitch with your chit chat / Just show me where your dick’s at” can be countered by the (completely true) fact that she made a 1500 on her SAT and has an IQ of over 140. 18 That’s part of the challenge that Kesha faced in a quest for critical attention that she seemed only vaguely interested in—no one this smart could be this sexually voracious, etc. And it stops there, rather than accepting that she is smart and her music about fucking is too. In a line like “show me where your dick’s at,” the female libido emerges uncensored, rare even in the kind of flirty idiom of the singers she’s often compared to. 19 She has admitted that the title of “Gold Trans Am” is a reference to her vagina, as the song is an innuendo that gets progressively less subtle as she tells someone with a “sweet ass mullet” to “come on, climb into my golden cockpit.” 20 On Bangers, also produced by Dr. Luke, Miley Cyrus only goes there once, when she sings “You’re sexy sexy I got things I want to do to you. Make me, make me, make my tongue just go do-do-do,” and there it’s got all the weird, unavoidable baggage of Hannah Montana singing to Spongebob Squarepants, part of a highly orchestrated career reinvention. 21 The rest of Miley’s album repeatedly reminds us how much MDMA she does. It was sort of like the classic Onion article where Marilyn Manson goes “Door-to-Door Trying to Shock People.” 22 It required the accompanying act of a foam finger, appropriating black culture, and Robin Thicke to really hammer home that you couldn’t keep Miley on the farm. 23 Miley’s most significant evolution wasn’t into the naked girl on top of the “Wrecking Ball,” but into what she’s done in recent, more assured and interesting, less self-consciously audacious albums. 24 When Kesha sang “Come put a little love in my glovebox,” she didn’t have to explain to anyone who she was or what she meant.

Admittedly, that’s all a critical and aesthetic conversation that wasn’t really happening, while the real issue was the relentlessly political and social commentary stirred when Kesha’s trial with Dr. Luke went loggerheads. The response was predictable: if Kesha sang this openly and frankly about sex, then she surely invited this powerful, successful man into her “glovebox,” and everything that followed is just part of the glitter, sex, and Jack Daniels-fueled narrative that she bragged about on Cannibal. Unfortunately, the video evidence that might have cemented her characterization in the public eye was her Luke-produced reality TV show My Crazy Beautiful Life, where Luke’s frequent cameos posit him like a paternal football coach on a sitcom at worst, and an enabling muse/avatar of supportive male sensitivity at best. 25 And that helped him gear a story toward countless judges that he was her port in the storm, rather than someone who Kesha had helped establish as a hit maker. She was the sexual aggressor because, in her songs, she’s the sexual aggressor. And considering that tautology, Kesha continually going back to court to be told that she was the person she proudly announced herself to be in her songs, and thus couldn’t be raped, is a level of courage and persistence in the face of astounding repeated humiliations. And she just kept showing up.

She doesn’t erase that humiliation. It haunts Rainbow. The rest of the album defies easy categorization, even as it aims to be what she later calls “a hymn for the hymnless.” She duets with fellow Nashville native Dolly Parton, chants songs called “Praying” and “Hymn,” and warbles a playful but melancholy song (written by her Mom) about taking Godzilla to the mall that wouldn’t be out of place in Raffi’s catalog of juvenile lyrics if it weren’t that the woman singing it had a similarly monstrous reputation. In their usual project of damning with faint praise, Pitchfork claims that “virtually every pop star of the early ’10s has written off the gonzo sound just as Kesha had,” which suggests they thought the spoken-word part about “being born from a rock spinning in the aether” was not the kind of thing even Gonzo the Muppet would find weird. 26 But nonetheless, the takeaway in more or less every review is that Kesha has abandoned the other coaxing voices and is listening to her own—what’s emerging is now “authentic,” because it’s also “adult” and “serious” (she just turned 30). That’s fair, but it’s too easy; she never had a reason to make something this emotionally resonant before. Case in point, Warrior.

Released in 2013, Warrior was anticipated as the raucous follow-up to Cannibal and Animal, where she would double-down on bad taste and parasitically devour the zeitgeist that she would capture. But it didn’t. With his typical sympathy, Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone noted that her “crudest, cheapest, cheesiest ideas are her best,” and that Warrior had replaced that attitude with a tendency for sensitive balladeering. 27 As the titular opening song proclaims:

We were born to break the doors down Fightin’ till the end It’s something that’s inside of us It’s how we’ve always been… 28

Headlined by the similarly anthemic yet slightly anemic lead single “Die Young,” Warrior strained for substance. It felt like a bit of a concession that no one was demanding and, even if they did, it didn’t seem like she would make a song about empowerment and independence, which had previously been implicit. Even her duet with Iggy Pop mixed trashiness with higher aspirations; she pushed back against the stupid world instead of reveling in its stupid excesses. As opposed to her peers, she was not rumored to be talking about “feminism and collective human creativity” with Slovenian heartthrob philosopher Slavoj Žižek. She was still going on Jimmy Kimmel to talk about exorcising a ghost from her vagina. Her reality show prominently features her mom dressed as a penis and Kesha tasting her own pee. 29 But Warrior was supposed to be her Like a Prayer, and it ended up being her …But the Little Girls Understand, the follow-up to Get the Knack that you forgot existed.

So it wasn’t surprising in the wake of the recent court battles that Kesha revealed the production was “strained.” Regarding “Die Young,” which was unfortunately released nearly immediately after the 2012 Newtown massacre, she states “I did NOT want to sing those lyrics and I was FORCED to.” 30 Fans put out a petition trying to emancipate her from Dr. Luke, claiming that he was “controlling Kesha like a puppet.” 31 The album’s relative failure could be easily connected to Luke’s inhibiting influence, as Kesha wanted to rock a bit more. She realized—like the Beach Boys realized about surfing, but Bobby “Boris” Pickett never apprehended about Dracula—that you could only sing so many songs about being in a club. 32 If Kesha’s energy was still evident, it was in spite of the oppressive strain of mediocrity that Luke trapped her in at the height of his (literally) hands-on machinations. The way Kesha’s origin story is portrayed is illuminating. It was almost universally reported that Luke picked her, practically at random, to record a hook for Flo Rida’s 2009 song “Right Round,” which has all the apocryphal star making mythos of Lana Turner being discovered at Schwab’s Drug Store. 33 A 2010 Billboard article about Kesha minimizes her contribution with phrasing that suggests an apparent lack of creative agency to elevate Luke and his maestro-centric narrative: “Luke was working on a track with Flo Rida … and the two decided they needed a female hook. Luke pulled Kesha into the studio and within two months, ‘Right Round’ was an international No. 1 …” 34 Kesha was never compensated for her contribution. This was one of Luke’s earliest hits, and even he admitted that the song wasn’t working until her involvement, though it had six writers, one of whom was Bruno Mars.

The typical posture of female pop stars since Madonna has been, essentially, “You think you understand me but you don’t.” It’s the theme behind Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space” and Lady Gaga’s Artpop and even Beyonce’s transcendent Lemonade (“Y’all haters corny with that illuminati mess”). 35 See simply the title of Swift’s Reputation, or the way Katie Perry’s Witness serves as a verb and not a noun. 36 In the face of spectacle and grandeur, we’re told that the best way to enjoy it is through passive, uncritical, even inert adoration. It’s what cultural scholar Joseph Roach succinctly describes as “it,” or “a certain quality, easy to perceive but hard to define, possessed by abnormally interesting people.” 37 Such performers contain “inducing asymmetries” that “register in the mind of the spectator as a miracle of unstable but inevitable harmonies.” 38 For example, in 1990 when she was the most relevant pop artist on the planet, Madonna would call this voguing, a highly stylized act of escape, erasure, resistance, and rebirth that comes through “strik[ing] a pose.” 39

Erasure is pivotal, yet fraught. bell hooks argued that Madonna’s celebration of the gay Harlem vogue culture is deeply problematic and “enables her to colonize and appropriate black experience for her own opportunistic ends, even as she attempts to mask her acts of racist aggression as affirmation.” 40 The highlight of the song “Vogue” catalogs exclusively white celebrities of a glamour era (“Greta Garbo and Monroe / Dietrich and Dimaggio”) before inviting them to “strike a pose.” 41 In this sense, Madonna—and perhaps those who imitate her–”colonize[s]” a culture that she exoticizes in order to “realize the dream of autonomous stellar individualism.” 42 To Madonna’s credit, she has still managed to become a gay icon. It”s fascinating to think what hooks would think of Kesha.

Regardless, such gestures are retaliatory, and work particularly well in live performances and music videos, particularly for the kind of impresario and curator of identity that Swift has become since the release of 1989. And because of what Roach describes as this tendency for female pop stars to present these asymmetries as unified, a perceived resistance (“haters,” for instance) is essential to the construction of artistic identities. The “you” in Swift’s recent “Look What You Made Me Do” could be either the fans angry at her evolution, some highly publicized paramour, perpetual irritant Kanye West, or the media. 43 Whatever: you – not he or even they – made her create an album almost entirely about her Reputation. But in conflating them, these opponents become bewilderingly abstract, even as they shout to the pressures women face when they have the status of an icon pushed upon them. As Rebecca Lush has written, Lady Gaga constructs “performance identity … in a way that deliberately obscures her core personal identity.” 44 In her “Aura,” it’s just that—a curtain she hides behind that only certain people get invited to pass, even though everyone wants to. In the lyric, “Do you wanna touch me, cosmic lover,” Gaga teases what’s at the heart of performance and spectacle by, as Lush writes, “relying on extreme opposites: covered body versus exposed body, good versus bad, famous versus unknown.” 45 Of course, Gaga has been such an affirming advocate of the LGBT community that it was considered activism for her to perform in the proximity of Mike Pence at the Super Bowl. And this only further works to mystify the contradiction; she is an artificiality that can constantly change, that cannot be known, and yet to whom you should attach yourself as one of her “little monsters” in an attempt to diversify the world.

One of the more telling ramifications of this came in 2011, in the wake of Rebecca Black’s viral fiasco “Friday.” Black’s song brought to prominence Ark Music Factory, an organization dedicated to taking non-famous children and giving them the experience of becoming a vaguely convincing simulacrum of an existing popular musician. Also on their roster at the time was eight-year old “CJ Fam,” a Curly Sue type who sang a song she wrote called “Ordinary Pop Star.” 46 In the video that accompanies the song, CJ defiantly announces that she has rejected the trappings of fame (mostly limos and cameras) that she has never experienced in her eight years as a person we have never heard of, to embrace the “average” life of which she has never experienced anything but. “I wanna have a regular life again,” she says in her strange debut, imagining famous young women who have irregular lives. While almost certainly conceived by Ark studio boss, affable Nigerian Patrice Wilson, the song nonetheless crystallizes the dream that gets so constantly refracted through female pop stars and their encounters with the media. “I wanna be who I am,” she sings, “and who I am is CJ Fam.”

A striking comparison might be found in female poets of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century, who often had to deal with combative masculine critics. One of the most colorful is Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673), the Duchess of Newcastle. After the Restoration in England, the monarchy of the swarthy Charles II released the dammed-up sexual energy of Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan autocracy. Yet even against this colorful backdrop, Cavendish was extraordinarily weird. She wrote a five-hundred-page book about science that included a proto-feminist Utopia filled with hermaphroditic animal people. She received a rare invitation to a Royal Society laboratory demonstration and showed up with a “very pretty black boy” who treated this most solemn of scientific spaces like a playground, while she wore a “dress so antick” that Samuel Pepys, whose diaries serve as a tour guide for Restoration culture, said he did “not like her at all, nor did hear anything that was worth hearing.” 47 Looking back before a recent critical recovery of Cavendish’s legacy by feminist scholars, Virginia Woolf (not a fan) classified Cavendish as “crack-brained and bird-witted,” with the “freakishness of an elf.” 48

On the frontispiece of several of Cavendish’s works of plays, poetry, letters, or fiction was an image of herself as a statue, with a poetic inscription that begins with the lines, “Here on this Figure Cast a Glance./ But so as if it were by Chance, /Your eyes not fixt, they must not Stay /Since this like Shadowes to the Day / It only represent’s …” 49 If what Roach describes as the “It” figure is an ultimately illusive vision of “inevitable harmonies,” Cavendish turns to the spectator and their inability to correctly see “abnormally interesting people,” who are “Shadowes.” That gets at the heart of Gaga fronting us about her aura—the desire to interpret these shadows, to see behind the curtain, says more about our desire than the phantasm she creates.

Like a sundial, Cavendish casts shadows while the world moves around her. But Kesha is constant movement, destruction, and explosions. In that sinister laugh from “Blow,” Kesha announced supreme defiance. Contributing to a Pitbull rap, when she’s “yelling timber,” it’s the closest we get to a warning for the dance floor she’s about to raze. 50 Yet in these songs, it wasn’t a sense that you couldn’t know her, just that she would trigger the dynamite if you got too close.

The sarcastic aside, “we can’t take you anywhere,” is richly self-reflective in a song like “Godzilla,” and it should probably be read as one of the smarter versions of those not-particularly sympathetic diatribes celebrities go on occasionally about how difficult it is to go to the grocery store because of TMZ or autograph seekers. It’s difficult to say this was her Mom’s intent in writing this playful song. But if Godzilla made trouble in the “food court,” it’s not the food court’s fault. 51 This is coming from a woman who defined herself as an “animal” and a “cannibal,” and it’s a powerful statement about the shame she must have felt coupled with the damage she could unleash: “I’ll bring thunder, I’ll bring rain,” she shouts on “Praying”, “When I’m finished they won’t even know your name.” 52 Despite the title’s suggestion of reconciliation and harmony, Rainbow is replete with anger and shame, with coming to terms with a history of messy emotions in a way that does not pretend they didn’t happen.

Blowing Up: Kesha’s Anger

For female pop stars specifically, and women in general, anger is untoward and indecent. In her recent book, Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger, Rebecca Traister summarizes this attitude: “women who talked too loudly and aggressively were considered immensely unappealing, sexually and intellectually, by the men whose opinions still shaped the world.” 53 To wit, the diagnosis of hysteria was associated with the uterus rather than the brain, and the association of femininity with hysterical symptoms still recurs in popular, pseudo-scientific understandings of the way mental illness works. In the late nineteenth-century, the French physician Auguste Fabre wrote, “all women are hysterical and … every woman carries with her the seeds of hysteria. Hysteria, before being an illness, is a temperament, and what constitutes the temperament of a woman is rudimentary hysteria.” 54 Anger is ugly, never pretty, and it’s for this reason that consumers of popular culture traditionally embrace male singers who are angry because they are honest or unfiltered, while challenging or generally mocking women who do the same. Swift’s Reputation features lines like “I bury hatchets, but I keep maps of where I put ‘em,” and it was treated critically with confusion and bemusement and frustration. 55 When Eminem, Kendrick Lamar, Kanye West, or Morrisey are angry, it’s a sign of depth and exciting vulnerability, a refusal to be silent. On an allmusic.com list of “Angry Albums,” there are only two entries that feature women—Sleater-Kinney’s Call the Doctor and P.J. Harvey’s Rid of Me—and those traffic in an alternative idiom that isn’t rewarded by heavy radio play. 56 In the 1990s, movements like Riot Grrrl, and the bands like Bikini Kill and Bratmobile that were identified with them, were essentially outsider, punk artists whose existence was predicated on a rejection of the desire for mainstream popularity. Meanwhile, bands like Nirvana, Rage Against the Machine, and Pearl Jam became arena rock and MTV staples, despite operating on a similar ethos, and were considered all the more cool for ostensibly rejecting stardom while having it fall into their laps. 57 Taylor Swift is so popular at this point that everything she does is news, but the general sentiment “why are you still so angry?” doesn’t apply to her male peers.

In “The Uses of Anger,” Audre Lorde writes that “Anger is loaded with information and energy;” it is “the grief of distortions between peers, and its object is change.” 58 She continues,

It is not the anger of other women that will destroy us, but our refusals to stand still, to listen to its rhythms, to learn within it, to move beyond the manner of presentation to the substance, to tap that anger as an important source of empowerment. 59

In Lorde”s productive dichotomy between “presentation” and “substance,” there’s an important understanding of the need for women to be rhetorical and persuasive in their use of anger, while also refusing to reject forms of anger that seem unpresentable. As Traister writes,

Anger is often an exuberant expression. It is the force that injects, intensity, and urgency into battles that must be intense and urgent if they are to be won. More broadly, we must come to recognize our own rage as valid, as rational, and not as what we’re told it is: ugly, hysterical, marginal, laughable. 60

There’s also a sense that anger doesn’t have to be retaliatory, and it doesn’t have to lead to any particular outcome. It just needs to be felt, and the people feeling this “force” don’t need to be told not to feel it.

Rainbow is an angry album for these reasons, even if it seems less raucous and at times bafflingly elusive. Without the kind of playfulness that Swift has been deploying, she shouts “Shake that ass, don’t care if they talk about it / Fuck all that, haters, just forget about ‘em.” 61 Here, Kesha is not, as Swift famously recommended, shaking it off, but angrily shouting back, “I’ve decided all the haters everywhere can suck my dick.” Here, she mimics the angry, male voice in a way that belittles complaining men as it calls attention to her own status as victim. Similarly, on “Hunt You Down,” one of two songs that embraces country tropes, she imagines assaulting an unfaithful lover: “Just know that if you fuck around, / Boy I’ll hunt you down.” 62 In an interview with NPR, she explained:

I remember listening to a song where a guy was talking about how he had his revolver in his pocket, and he was going to shoot the girl because she was sleeping with his best friend or something. And I was like, “OK — Well, if a man can say that, then I’m gonna write a song about how if you cheat on me, I’m gonna kill you.” So that’s what “Hunt You Down” is — it’s kind of my feminist, tongue-in-cheek response to all the outlaw cowboy songs from the male perspective about cheating women. 63

While “Hunt You Down” is sly and lively rather than bitter or angst-filled, it fits into Rainbow’s thematic content, in which powerful male voices should be corrected or silenced. Listening to the album can be jarring, as Rainbow alternates between songs that are lighthearted and those that are soul-baring with an uncomfortable honesty, reflecting the embattled personality of their creator who is trying to laugh amidst the pain.

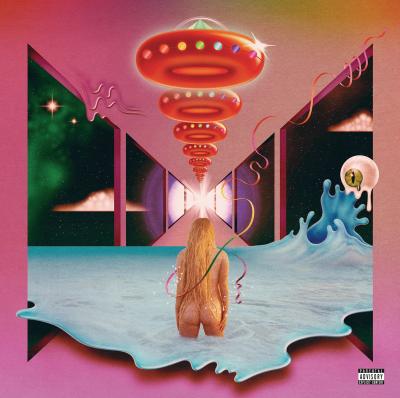

On the piano-based “Praying” (co-written with Macklemore) she emits a broken, strained high note far out of autotune range. That screech represents a new voice emerging from a woman who might previously have seemed incapable of this kind of emotional anger and deep sentiment. And to be clear, she’s not praying; she’s telling her abuser he ought to. In the earlier “Die Young,” she didn’t seem to care if she lived beyond a particularly riotous night of dancing and clubbing. On the title track of Rainbow, she now sings “I’m falling right back in love with being alive.” 64 The pathos is sometimes wrenching, and it goes the other way in an empowerment ballad called “Woman” that is less “I Am Woman” and more “Hear me ROAARRR.” She’s kept the energy, the humor, and even the perverse intelligence behind her earlier earworms, while connecting to a new side that has immense promise—a naked honesty that reflects the album’s cover, where a bare-assed Kesha steps into the water to be somehow baptized. That image isn’t erotic, which is what makes it revelatory, a promise to share the experience of redemption openly and publicly.

Salvation Mountain

One of the most affecting moments on My Crazy Beautiful Life has Kesha on a British tour visiting a young fan in Manchester. 65 He’s been bullied, and he gives her a scrapbook with a message about how much her song “Animal” helped him. “Her music has set me free,” he says. Kesha hugs him and cries. Despite a suggestive title, “Animal” is probably one of her most overtly conventional and asexual songs, and it’s hard to see how a song written to a would-be lover about being “into the magic” would mean so much to a British teenage boy. However, it’s also a song about being alive when you might feel dead, and it’s uncanny how much she sings at a pitch that other outcasts hear clearer than others.

Screenshot from My Crazy Beautiful Life

In the video for “Praying,” Kesha offers a spoken word overture as she imagines herself floating at sea:

Am I dead? Or is this one of those dreams? Those horrible dreams that seem like they last forever? If I am alive, why? If there is a God or whatever, something, somewhere, why have I been abandoned by everyone and everything I’ve ever known? I’ve ever loved? Stranded. What is the lesson? What is the point? God, give me a sign, or I have to give up. I can’t do this anymore. Please just let me die. Being alive hurts too much. 66

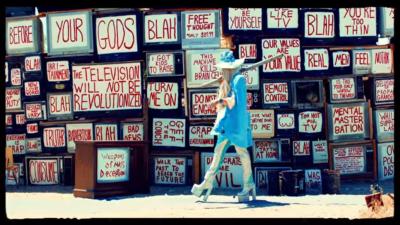

Directed by Jonas Åkerlund, the Swedish director of many Madonna and Lady Gaga videos, the video for “Praying” is miasmic and not particularly empowering. It is set almost entirely at “Slab City” (home of squatters and seekers, and made famous in the 2007 film Into the Wild) and its colorful, pop-art spectacle centerpiece, Salvation Mountain. Here there’s a motif that religion and prayer might help us but we’re really not sure. Ultimately, the music revivifies her, leading Kesha to once again engage in various acts of destruction—against the messages, against attackers with pig faces, against the black-and-white world that drained her of life. She walks in front of the “TV Wall,” a home for derelict consoles that have their messages literally painted on their screens: “Free Thought, only $89.99,” “Real Men Feel Nothing,” and apropos considering it’s one of the titles of an early song, “Blah Blah Blah.”

The question “Is salvation possible?” dominates the video and the album, and refuses to be answered. Salvation Mountain is folk art geography that relies on crowd-sourced curation and preservation, and it’s difficult to figure out whether its kitsch is ironic or earnest. In one shot, as Kesha stands in the shadow of a giant cross, it’s paralleled with the appearance of a whale in the ocean. Both are highly symbolic, but neither, she seems to be saying elliptically, will actually save her—just like prayer won’t save her unrepentant accuser. But as a visual backdrop, the messages of Slab City, whether rich or recycled, consciously acknowledge that singers like Kesha—and women in general—are defined by these voices and their absurd messages that virile young artists can’t ignore. Luke’s mediocrity provided a platform that Kesha could never escape, and still to some degree can’t because, as it’s been widely reported, he’s still profiting from an album that (however elusively) attacks him. 67

Kesha’s clear expression of trauma throughout the album is underscored by a hope that will come through both resistance and a refusal to be silent, exemplified by the song’s defining yelp. And for that reason, though it preceded Me Too, it clearly anticipated it. The lines

You brought the flames and you put me through hell I had to learn how to fight for myself And we both know all the truth I could tell

crystalize with a blunt simplicity the process and its potential resolution, the move from “You” to “I” to the “truth” and the empowered voice that will tell it. Traister described Me Too’s revelation of the complex structural geography of gender paradigms as resembling “the shock of the house lights having been suddenly brought up.” 68 And as we were all reeling in celebration and confusion, Kesha’s voice was unified and focalized in a powerful moment at the January 2018 Grammys when she was joined by an activist choir of women in white who joined her in singing those lyrics. If the “Praying” video emphasized her forlorn loneliness as an outcast in a weird landscape, the Grammys performance punctuated the journey it represents with a solidarity that she earlier had grimly worried she couldn’t get. This place is gonna blow.

Conclusion

.

“Why,” Kermit the Frog once asked, “are there so many songs about rainbows?” 69 He didn’t answer it, only acknowledging a vague “connection” that we feel or might feel. But rainbows come after storms, and they’re perhaps more beautiful when the climate has been more devastating, as Noah learned when the divine voice told him, “Never again will the waters become a flood to destroy all life.” 70 On Rainbow, Kesha is telling this to herself and doesn’t need deific confirmation. Maybe that’s why she looks so forlorn as she rests atop a mountain that cartoonishly explains that “God is Love.” When she tells her assaulters, “I hope you’ve been praying,” there’s no promise or admission of wrong, and there’s no real ambition for resolution or reparation. There’s simply a sense that people who have no regrets shouldn’t be forgiven. For everyone else, there’s the connective tissue of the rainbow that comes no matter how awful the storm:

And I know that I’m still fucked up

But aren’t we all, my love?

Darling, our scars make us who we are

Once consuming, Kesha is now absorptive in the compassion that draws people in. In almost every early video, she didn’t just go to the party, she was the party. And now that party is unifying victims and outcasts; as she announces in “Hymn,” “Yeah we keep on sinning, / Yeah we keep on singing.” Pronouns are pivotal for Kesha, the “we” who she brings together, the “you” who should be praying, the “I” who is open and now surprisingly transparent. In a typically spellbinding and weird interview with NPR, she claimed that she’s “a little bit of an empath and a fragile heart for this world.” 71 Elsewhere, she’s a “mother-fucking woman.” That’s not a dichotomy; she’s not unifying two things that shouldn’t be unified. It’s not Taylor Swift saying to the bastards she’ll just “Shake It Off,” Ariana Grande chanting, “Thank You, Next,” or Selena Gomez offering to “Kill ‘Em with Kindness.” This is not to imply that those songs are reacting to same kind of victimization that Kesha endured, but the sentiment suggests that justice is unnecessary if you can just accept that, as Swift sings, “haters gonna hate… / I’m just gonna shake.” 72 As Swift characterizes it, passive aggressive “shaking” is easy; for Kesha, “praying” is not. Kesha’s response is to show us the deep, messy reservoir of emotion she’s been feeling. Part of what has been so liberating about Me Too is that it not only opened the possibility of exposing and destroying what Traister calls “hierarchies of harm and privilege,” but also of displaying those emotions in a way that doesn’t have to be covered up publicly. 73 Kesha’s anger is not tidy, nor is her sadness, as shown in her refusal to dismiss it to keep producing music during what should have been the most productive years of her career. Rainbow captures what an abused woman has lost, what she hopes to get back, and the trauma that she refuses to shake off. Kesha occupies a difficult emotional register that can be both/and instead of either/or, and that’s a place that’s the sort of resistance to classification that we’re still a bit uncomfortable with female pop stars occupying. Yet this is a start.

In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan wrote of the near impossibility to “confor[m] outwardly to one reality, while trying to maintain inwardly the value it denies.” 74 As on “Praying,” Kesha’s startling vulnerability is a strength, a perplexing unity that should be obvious in the “We” that she invites us to join. Kesha’s combination of power and fragility, of living through shame and still announcing a desire to live furiously, defines Rainbow and we can only hope will be a feature of what follows. We weren’t expecting such profound compassion from the author of “Sleazy.” Because the rainbow is not merely a meteorological phenomenon, it’s a palate on which she will “paint the world.”

Bibliography

“Angry Albums | Mood Music.” AllMusic. Accessed May 16, 2019. https://www.allmusic.com/mood/angry-xa0000000695/albums.

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1986.

Cavendish, Margaret. Plays, Never before Printed. London, 1668.

Clements, Erin. “Kesha Made Bra From Her Fans’ Teeth | HuffPost.” Huffpost Celebrity. November 21, 2012. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/kesha-bra-from-fans-teeth_n_2170202.

Corner, Lewis. “Flo Rida Hasn’t Spoken to Kesha about Her Legal Battle.” Digital Spy, June 10, 2016. (http://www.digitalspy.com/music/a797335/flo-rida-hasnt-managed-to-reach-out-to-kesha-during-her-legal-battle-with-dr-luke/).

Coscarelli, Joe. “Kesha, Even With a Liberated New Album, Remains Tied to Dr. Luke.” The New York Times, January 20, 2018, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/09/arts/music/kesha-rainbow-dr-luke-lawsuits.html.

Cottom, Tressie McMillan. “Brown Body, White Wonderland.” Slate Magazine, August 29, 2013. https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/08/miley-cyrus-vma-performance-white-appropriation-of-black-bodies.html.

Cox, Jamieson. “Taylor Swift: Reputation.” Pitchfork, November 13, 2017. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/taylor-swift-reputation/.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique (50th Anniversary Edition). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013.

Friedman, Jaclyn. “The Problem With ‘New’ Taylor Swift Is That Nothing’s Changed.” Glamour, November 9, 2017. https://www.glamour.com/story/the-problem-with-new-reputation-taylor-swift.

Friedman, Uri. “No, Lady Gaga Is Not Friends with Marxist Philosopher Slavoj Žižek.” The Atlantic, June 22, 2011. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/06/lady-gaga-and-marxist-slavoj-zizek-friendship-wasnt/352046/.

Hawks, Asa. “Kesha at the 2010 MTV EMAs - European Music Awards.” Starcasm, November 7, 2010. https://starcasm.net/photos-keha-at-the-2010-mtv-emas/.

“High Court Won’t Let Singer Kesha out of Contract with Man She Says Raped Her.” Women in the World (blog), February 19, 2016. https://womenintheworld.com/2016/02/19/kesha-ordered-by-high-court-to-fulfill-6-record-obligation-with-her-alleged-rapist/.

hooks, bell. Black Looks: Race and Representation. New York: Routledge, 2014.

“Kesha Clarifies Being ‘Forced’ to Sing ‘Die Young.’” Rolling Stone (blog), December 21, 2012. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/keha-clarifies-being-forced-to-sing-die-young-59682/.

“Kesha: ‘Seeing My Mother in a Penis Suit on Stage Was Very Emotional.’” Pressparty. Accessed May 14, 2019. https://www.pressparty.com/pg/newsdesk/kesha/view/69070/.

“Kesha – Sleazy Lyrics.” Genius. Accessed May 13, 2019. https://genius.com/1090171.

“Kesha Hosts Naked Body Paint Parties.” CTV News, February 8, 2012. https://www.ctvnews.ca/kesha-hosts-naked-body-paint-parties-1.765478.

“Kesha v. Dr. Luke.” In Wikipedia, May 10, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kesha_v._Dr._Luke&oldid=896461156.

Lorde, Audre. “The Uses of Anger.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 25, no. 1/2 (1997): 278–85.

Lorusso, Marissa. “Kesha Walks Us Through Her ‘Rainbow,’ Track By Track.” NPR, August 11, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/allsongs/2017/08/11/542686805/kesha-walks-us-through-her-rainbow-track-by-track.

Lush, Rebecca. “The Appropriation of the Madonna Aesthetic.” In The Performance Identities of Lady Gaga: Critical Essays, edited by Richard J. Gray II. Jefferson: Macfarland and Company, 2012.

“Marilyn Manson Now Going Door-To-Door Trying To Shock People.” The Onion, January 31, 2001. https://entertainment.theonion.com/marilyn-manson-now-going-door-to-door-trying-to-shock-p-1819565904.

Martins, Chris. “Kesha Fans Petition to Free ‘Pop Puppet’ From Dr. Luke’s Evil Grasp.” Spin, September 24, 2013. https://www.spin.com/2013/09/kesha-dr-luke-petition-fans-contract-albums-career-puppet/.

Pepys, Samuel. The Diary of Samuel Pepys. Edited by Robert Latham and William Matthews. Vol. 8. 11 vols. Berkeley: California UP, 1974.

Ponder, Jon. “Schwab’s Drug Store: Where Lana Turner Was Not Discovered.” Playground to the Stars, June 4, 2013. http://www.playgroundtothestars.com/2013/06/schwabs-drug-store-where-lana-turner-was-not-discovered/

Roach, Joseph. It. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Sheffield, Rob. “Warrior.” Rolling Stone, December 4, 2012. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/warrior-116381/.

Showalter, Elaine. “Hysteria, Feminism, and Gender.” In Hysteria Beyond Freud, edited by Sander L. Gilman, Helen King, Roy Porter, G.S. Rousseau, and Elaine Showalter. Berkeley: California University Press, 1993.

St. Asaph, Katherine. “Kesha: Rainbow.” Pitchfork, August 11, 2017. https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/kesha-rainbow/.

“SAT Scores of the Rich and Famous.” The 6th Floor Blog (blog), March 5, 2014. https://6thfloor.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/05/sat-scores-of-the-rich-and-famous/.

Sullivan, Matt. “KESHA and the Not-Quite-72 Virgins in Her Own Personal Heaven.” Esquire, August 13, 2009. https://www.esquire.com/kesha-pics-081309.

The Ringer Staff. “What Is Taylor Swift Doing?” The Ringer, August 23, 2017. https://www.theringer.com/music/2017/8/23/16193036/taylor-swift-reputation-analysis.

Traister, Rebecca. Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger. Simon & Schuster, 2019.

———. “We Are All Implicated in the Post-Weinstein Reckoning.” The Cut, November 12, 2017. https://www.thecut.com/2017/11/rebecca-traister-on-the-post-weinstein-reckoning.html.

Werde, Bill. “Kesha: The Billboard Cover Story.” Billboard. Accessed May 14, 2019. (https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/959321/keha-the-billboard-cover-story).

Wikipedia contributors, “Kesha v. Dr. Luke,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kesha_v._Dr._Luke&oldid=896461156) (accessed May 16, 2019).

________, “Right Round,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, (https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Right_Round&oldid=893148976) (accessed May 14, 2019)

Woolf, Virginia. The Common Reader. First Series. London: Hogarth Press, 1962.

Yamato, Jen. “Inside Kesha’s Battle Against Dr. Luke: Allegations of Rape, Sketchy Deleted Photos, and More.” The Daily Beast, February 23, 2016. https://www.thedailybeast.com/inside-keshas-battle-against-dr-luke-allegations-of-rape-sketchy-deleted-photos-and-more.

DISCOGRAPHY

Ascher, Kenneth and Paul Williams. The Muppet Movie: Original Soundtrack Recording. A&M Studios, 1979. Vinyl Recording.

Beyonce. Lemonade. Parkwood Entertainment and Columbia Records, 2016, Compact Disc.

Kesha. Animal. RCA Records, 2010, Compact Disc

––. Cannibal (EP). RCA Records, 2010, Compact Disc

––. Rainbow. RCA Records, 2013, Compact Disc.

––. Warrior. RCA Records, 2012, Compact Disc.

Madonna, I’m Breathless. Sire Records, 1990, Compact Disc.

Perry, Katy. Witness. Capitol Records, 2017, Compact Disc.

Pitbull. Meltdown. RCA Records, 201, Compact Disc.

Swift, Taylor. 1989. Big Machine Records, 2014, Compact Disc.

––. Reputation. Big Machine Records, 2017, Compact Disc.

Footnotes

- Asa Hawks, “Ke/$ha at the 2010 MTV EMAs - European Music Awards,” Starcasm, November 7, 2010, https://starcasm.net/photos-keha-at-the-2010-mtv-emas/.

- Kesha, “Party at a Rich Dude’s House,” Track #8 on Animal, RCA Records, 2010, compact disc.

- Matt Sullivan, “KESHA and the Not-Quite-72 Virgins in Her Own Personal Heaven,” Esquire, August 13, 2009, https://www.esquire.com/kesha-pics-081309.

- “Kesha - Tik Tok (Official Music Video),” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=iP6XpLQM2Cs

- Erin Clements, “Kesha Made Bra From Her Fans’ Teeth | HuffPost,” Huffpost Celebrity, Nov. 21, 2012, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/kesha-bra-from-fans-teeth_n_2170202; “Kesha Hosts Naked Body Paint Parties,” CTV News, February 8, 2012, https://www.ctvnews.ca/kesha-hosts-naked-body-paint-parties-1.765478.

- “Kesha – Blow (Official Music Video),” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=CFWX0hWCbng

- Jen Yamato, “Inside Kesha’s Battle Against Dr. Luke: Allegations of Rape, Sketchy Deleted Photos, and More,” The Daily Beast, February 23, 2016, https://www.thedailybeast.com/inside-keshas-battle-against-dr-luke-allegations-of-rape-sketchy-deleted-photos-and-more.

- Kesha, “Emotional,” Bonus Track 15 on Rainbow, RCA Records, 2017. Compact Disc.

- Kesha, “Sleazy,” Track 4 on Cannibal (EP), RCA Records, 2010. Compact Disc.

- Rebecca Traister, Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger (Simon & Schuster, 2019), 143. Portions of this book originally appeared as Rebecca Traister, “We Are All Implicated in the Post-Weinstein Reckoning,” The Cut, November 12, 2017, https://www.thecut.com/2017/11/rebecca-traister-on-the-post-weinstein-reckoning.html.

- Kesha, “Bastards,” Track #1 on Rainbow.

- Kesha, “Warrior,” Track #1 on Warrior, RCA Records, 2012. Compact Disc.

- Kesha, “Bastards.”

- Kesha, “We R Who We R.” Track #2 on Cannibal.

- Kesha, “Cannibal,” Track #1 on Cannibal.

- Kesha, “Grow a Pear,” Track #7 on Cannibal.

- Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1986), 52.

- Kesha, “Blah Blah Blah,” Track #6 on Animal. “SAT Scores of the Rich and Famous,” The 6th Floor Blog (blog), March 5, 2014, (https://6thfloor.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/03/05/sat-scores-of-the-rich-and-famous/).

- That’s not to say she’s always uncensored, however. As the Genius page for “Sleazy” reports, she adds innuendo to the “come” homonym in the next line with “over to your place.” In the demo, it’s “all over your face.” See “Kesha – Sleazy Lyrics,” Genius, accessed May 13, 2019, (https://genius.com/1090171).

- Kesha, “Gold Trans Am,” Bonus Track #14 on Animal.

- Miley Cyrus, “#GET IT RIGHT,” Track #8 on Bangers. RCA Records, 2010, Compact Disc.

- “Marilyn Manson Now Going Door-To-Door Trying To Shock People,” The Onion, January 31, 2001, (https://entertainment.theonion.com/marilyn-manson-now-going-door-to-door-trying-to-shock-p-1819565904).

- Tressie McMillan Cottom, “Brown Body, White Wonderland,” Slate Magazine, August 29, 2013, (https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/08/miley-cyrus-vma-performance-white-appropriation-of-black-bodies.html).

- “Miley Cyrus - Wrecking Ball (Official Video),” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=My2FRPA3Gf8

- My Crazy Beautiful Life. MTV, 2013.

- Katherine St. Asaph, “Kesha: Rainbow,” Pitchfork, August 11, 2017, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/kesha-rainbow/; Kesha, “Spaceship,” Track #14 on Rainbow.

- Rob Sheffield, “Warrior,” Rolling Stone, December 4, 2012, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/warrior-116381/.

- Kesha, “Warrior,” Track #1 on Warrior.

- Uri Friedman, “No, Lady Gaga Is Not Friends with Marxist Philosopher Slavoj Žižek,” The Atlantic, June 22, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2011/06/lady-gaga-and-marxist-slavoj-zizek-friendship-wasnt/352046/; “Kesha On Ghost Haunting Her Vagina – ‘I Had Dead People Inside Me,’” YouTube, Worldstarhiphopalert; “Kesha: ‘Seeing My Mother in a Penis Suit on Stage Was Very Emotional,’” Pressparty, accessed May 14, 2019, https://www.pressparty.com/pg/newsdesk/kesha/view/69070/; “Kesha Drinks Her Own Pee,” YouTube.

- “Kesha Clarifies Being ‘Forced’ to Sing ‘Die Young,’” Rolling Stone (blog), December 21, 2012, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/keha-clarifies-being-forced-to-sing-die-young-59682/.

- Chris Martins, “Kesha Fans Petition to Free ‘Pop Puppet’ From Dr. Luke’s Evil Grasp,” Spin, September 24, 2013, https://www.spin.com/2013/09/kesha-dr-luke-petition-fans-contract-albums-career-puppet/.

- “Bobby Pickett ‘Monster Mash,’” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=vNuVifA7DSU

- Lewis Corner, “Flo Rida Hasn’t Spoken to Kesha about Her Legal Battle,” Digital Spy, June 10, 2016, http://www.digitalspy.com/music/a797335/flo-rida-hasnt-managed-to-reach-out-to-kesha-during-her-legal-battle-with-dr-luke/; Jon Ponder, “Schwab’s Drug Store: Where Lana Turner Was Not Discovered,” Playground to the Stars, June 4, 2013.

- Bill Werde, “Kesha: The Billboard Cover Story,” Billboard, accessed May 14, 2019, https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/959321/keha-the-billboard-cover-story.

- Taylor Swift, “Blank Space,” Track #2 on 1989, Big Machine Records, 2014, Compact Disc; Lady Gaga, Artpop, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013, Compact Disc; Beyonce, “Formation,” Track #12 on Lemonade, Parkwood Entertainment and Columbia Records, 2016, Compact Disc.

- Though since Katy appears on the album cover covering her eyes and with an eyeball in her mouth where her teeth should be, it’s unclear if she’s witnessing us or we’re witnessing her. It’s a fascinatingly uneven album. Taylor Swift, Reputation, Big Machine Records, 2017, Compact Disc; Katy Perry, Witness, Capitol Records, 2017, Compact Disc.

- Joseph Roach, It (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), 1.

- Roach, It, 8.

- Madonna, “Vogue,” Track #12 on I’m Breathless, Sire Records, 1990, Compact Disc.

- bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (New York: Routledge, 2014), 241.

- Madonna, “Vogue.”

- hooks, Black Looks, 235.

- Taylor Swift, “Look What You Made Me Do,” Track #6 on Reputation.

- Rebecca Lush, “The Appropriation of the Madonna Aesthetic,” in The Performance Identities of Lady Gaga: Critical Essays, ed. Richard J. Gray II (Jefferson: Macfarland and Company, 2012), 181.

- Lush, 181. Lady Gaga, “Aura,” Track #1 on Artpop.

- “CJ Fam – Ordinary Pop Star!” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ToBXzgNjZE

- Samuel Pepys, The Diary of Samuel Pepys, ed. Robert Latham and William Matthews, vol. 8, 11 vols. (Berkeley: California UP, 1974), 8:243.

- Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader. First Series (London: Hogarth Press, 1962), 77.

- Margaret Cavendish, Plays, Never before Printed (London, 1668), a11.

- Pitbull (featuring Kesha), “Timber,” Track #1 on Meltdown, 2013, RCA Records, Compact Disc.

- Kesha, “Godzilla,” Track #13 on Rainbow.

- Kesha, “Praying,” Track #5 on Rainbow.

- Traister, Good and Mad, 25.

- Quoted in Elaine Showalter, “Hysteria, Feminism, and Gender,” in Hysteria Beyond Freud, ed. Sander L. Gilman et al. (Berkeley: California University Press, 1993).

- Taylor Swift, “End Game,” Track #2 on Reputation; The Ringer Staff, “What Is Taylor Swift Doing?,” The Ringer, August 23, 2017, https://www.theringer.com/music/2017/8/23/16193036/taylor-swift-reputation-analysis; Jamieson Cox, “Taylor Swift: Reputation,” Pitchfork, November 13, 2017, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/taylor-swift-reputation/; Jaclyn Friedman, “The Problem With ‘New’ Taylor Swift Is That Nothing’s Changed,” Glamour, November 9, 2017, https://www.glamour.com/story/the-problem-with-new-reputation-taylor-swift.

- “Angry Albums | Mood Music,” AllMusic, accessed May 16, 2019, https://www.allmusic.com/mood/angry-xa0000000695/albums.

- A notable, but complicated, exception to this is Courtney Love, whose second album with Hole went multi-platinum. The album was released one week after the suicide of her husband, Kurt Cobain of Nirvana. Love took steps to become more mainstream following this, starring in well-received movies where her performances were widely praised. Though she continues to tour and release music, none of her songs have charted since 1995.

- Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger,” Women’s Studies Quarterly 25, no. 1/2 (1997): 281, 282.

- Lorde, “The Uses of Anger” 282.

- Traister, Good and Mad, 27.

- Kesha, “Let ‘Em Talk,” Track #8 on Rainbow.

- Kesha, “Hunt You Down,” Track #9 on Rainbow.

- Marissa Lorusso, “Kesha Walks Us Through Her ‘Rainbow,’ Track By Track,” NPR, August 11, 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/allsongs/2017/08/11/542686805/kesha-walks-us-through-her-rainbow-track-by-track.

- Kesha, “Rainbow,” Track #8 on Rainbow.

- Kesha: My Crazy Beautiful Life, Episode 1, “Taking the Stage,” aired April 23, 2013, on MTV.

- “Kesha – Praying (Official Video)”, YouTube Video, 4:59, Kesha.

- Joe Coscarelli, “Kesha, Even With a Liberated New Album, Remains Tied to Dr. Luke,” The New York Times, January 20, 2018, sec. Arts, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/09/arts/music/kesha-rainbow-dr-luke-lawsuits.html.

- Traister, “We Are All Implicated in the Post-Weinstein Reckoning.”

- Paul Asher and Kenneth Williams (composers), “The Rainbow Connection,” Track #1 on The Muppet Movie: Original Soundtrack Recording, 1979, A&M Studios.

- Gen 9:15 (New International Version)

- Lorusso, “Kesha Walks Us Through Her ‘Rainbow,’ Track By Track.”

- Taylor Swift, “Shake It Off,” Track #6 on 1989.

- Traister, “We Are All Implicated in the Post-Weinstein Reckoning.”

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (50th Anniversary Edition) (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013).