Introduction - Jeff McMahon

In the early 1970s, I attended a public high school in suburban Southern California. I recall there were maybe one or two black students; none in any of my classes. My favorite teacher, whose 4-year Great Books course opened the world for me, was a racist, sexist arch-conservative, yet a perversely inspiring teacher. He frequently took students into Los Angeles to see film screenings (pre-home video), with the films of D.W. Griffith being his particular favorite. He presented the 1915 The Birth of a Nation as a historically accurate portrait of post-Civil War Reconstruction. I soon discovered the utter falseness behind that depiction, yet for many years conceded that the film remained “great art,” flawed yet exemplary in craft.

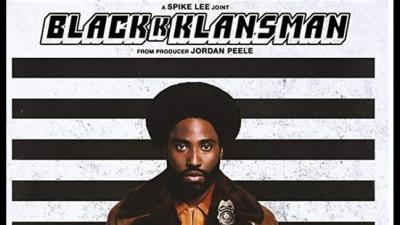

Watching Spike Lee’s recent BlacKkKlansman (2018), in an upstate New York arthouse with an entirely white audience, I thought it a sharp, disturbing, and very contemporary attempt to dig into American history and racism. Lee’s re-framing of Griffith’s film in one powerful scene made it all the more personally potent. I like Lee when he goes out on a limb with his coruscating cultural irreverence. So, I sensed, did most of the other people sitting with me in that theatre.

I intended to write about this context for my admiration, but realized that it would be far more interesting and instructive for me to ask younger colleagues to weigh-in, some of whom would have stood out in that crowded theatre. This process also forced me to more clearly understand the cultural perspective from which I viewed the film. Could it be that younger people received BlacKkKlansman differently, with the film not universally celebrated or even welcomed? And did my list of potential writers reflect that diversity? I asked colleagues for students and others they might recommend, and that list became more interesting. The subsequent responses surprised me; so did the people who were very critical of the film, who did not see it the way I did, or who liked it for reasons I had not anticipated.

I also saw this partial ceding of the authorial head of the table as part of my own education. Spurred by one of my students’ writing projects, I had recently embarked on personal research into the history of slavery, the middle passage, and racism in this country. During visits to the Whitney Plantation and the Legacy Museum/National Memorial for Peace and Justice (the “lynching museum”), I thought, “everyone in America should see this.” I had a similar reaction to BlacKkKlansman. Several of my responders, as you will see, brought something very different to the conversation, and, as is so often the case with incendiary material, I’m having to re-think just what is being burned. Our distance from a conflagration creates differences in our responses, but also makes the light more textured.

History is creatively repurposed in American culture, currently in shows such as Hamilton, The Slave Play, in music (This is America), and, as is argued here, in film. The more responses we listen to, the more we will understand not only the work itself, but the manner in which we are receiving it.

Nicole L. Martin

While it is possible that one could loosely describe Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman as a dark comedy, there is little humor to be found in the ritualistic violence against black bodies that Lee’s film seeks to exploit. I imagine that Lee himself would agree with this argument and perhaps claim this is precisely the point of the film. Yet the ritualized anti-black terror evoked within BlacKkKlansman is both troubling and dangerous. Contrary to popular belief, rituals are not merely symbolic—they do work in and have an effect on the world. BlacKkKlansman is a feature-length ritualization of white supremacist terror. Yes, Lee’s film is a dramatization. And, yes, the use of dark humor must be taken into consideration. But it would be naïve to think that BlacKkKlansman creates enough psychic distance for its audience to dismiss the film’s continued activation of antiblackness as immaterial. Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman resurrects ghosts that should remain buried—not out of ignorance toward pervasive terror but, rather, out of respect and care for how Black people continue to embody the effects of this trauma.

While watching BlacKkKlansman, I often found myself wondering for whom the film was made. It is my suspicion that the Klansmen (and their white women defenders) were not the target audience. If this is true, I see little need to explicitly connect the film’s fictionalized Klan with contemporaneous eruptions of white supremacist terror. Juxtaposing a temporally isolated cross-burning with footage from a neo-Nazi plowing into counter-protestors at the Unite the Right rally in August 2017 does not “unveil” a lingering presence of historical hate. Those of us who opted to watch BlacKkKlansman, especially if identifying as Black, likely do not need such a reminder.

And yet, to arrive at the film’s conclusion required our repeated submission to the ceremonial sanctification of white terror. There was a chilling ease to the delivery of anti-black rhetoric, particularly from John David Washington’s portrayal of Ron Stallworth. In fact, I could not help but feel traumatized on Washington’s behalf. Rituals are made real in and through the body, and racist rhetoric is a form of ritual. The reason why we do not say “the n-word” is not because of a moralistic need to be politically correct. We do not say “the n-word” because we know, deep down, that our naming—our rhetoric—shapes our practices, and our practices have material consequences.

The way BlacKkKlansman asked its actors and audience to play with this tradition of hate makes all of us complicit in its continued production. The Klan initiation scene where the fake Ron Stallworth is welcomed into the organization is broken up by actor Harry Belafonte’s historical narration of Black Civil Rights activism. In this scene, Black bodies are held in stillness, magnified on poster board, fixed in terror, while white bodies (and the “fact” of their superiority) are baptized into reverence and made supremely alive again. The shouts of “Black Power” at the end of Belafonte’s monologue do little to mitigate the authority forged by way of our watching its very creation.

This is where Lee’s film fails. How we remember is as important to our disruption of white supremacy as the what of our remembrance. Therefore, I would implore Lee and all creatives to consider the implication of our artistic practices in the way they replicate violence. BlacKkKlansman reminds us that the producer of anti-black violence must be handled with as much care as the subject of its vitriol.

Al Evangelista

Gestures create a space for solidarity. A warm smile, a familiar wave, some gestures only make sense to those who understand their context. The gestures in a room full of social justice organizers, for example, can represent both a response to and an attempt to subvert hegemonic structures. In January 2019, at the Racial Justice Institute lead by AORTA (Anti-Oppression Resource and Training Alliance) at Creating Change, a conference organized by the National LGBTQ+ Task Force, I was in a room with hundreds of people singing, “I got a right to the tree of life.” Led by freedom singer Wendi Moore-O’Neal, this feeling of unity in social justice work and song felt healing during these times of political disunity. Before the singing started I scanned the room to take in the space and make sure we were safe. I thought how vulnerable we were to sit in this conference room, all of us organizers, social justice workers, and art makers. I thought how easy it would be to inflict harm on so many, all at once, because we were all in this same space. Once we started to sing I did not feel afraid. Moore-O’Neal asked us to meet her “in the air” with our voices and when we did our collective voices gestured towards collective safety. This ebb and flow of safety is what I felt while watching covertness and gestures in BlacKkKlansman.

We move through the world with our bodies performing at all times with a lingering ambiguity as the meaning of our movements echo in others and ourselves, varying in relationship to shifts in power and privilege. Because of this ambiguity we listen to subscribed behaviors, take them on, and repeat them in order to be or feel safe. How fitting then to consider the coded bodily movements in BlacKkKlansman, a movie about policing; a movie that questions policing; a movie that questions whether we can be safer in systems by moving within them.

During the college assembly scene of BlacKkKlansman, Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins) goes through the process of being seen and forcing himself to be seen through his gestures. In this opening scene, Ture is the Black Student Association’s invited speaker and his mere presence sets a covert police operation into motion. Ture’s most powerful and repeated gesture during this scene is of pointing his finger; pointing emphatically to ask the Black Student Association to sit down, pointing at himself, at the world outside, and at an unseen energy he is trying to provoke. In his gestures, he also points to an oppressive history and a potential future. The gestures in this film, especially at the student rally, are weighted. Ture pushes back with his pointing finger. Why is it threatening for black college students to be in the same room organizing, so much so that they need to be tracked by the police? Ture points with the frustration of a man who hates that these questions even exist, yet one who knows that we move through a world with individuals who refuse to acknowledge these questions at all.

At Creating Change we were asked to stand up to sing. Our gesture as a community was and continues to be to stand and be present for one another. At Creating Change, there was another gesture in the space as well. Moore-O’Neal keeping the beat, snapping, keeping the group together, indicating time. Keeping tempo for a song from a time long ago, one that still brings solidarity. Just as we need Ture’s pointing gesture of accountability, we also need Moore-O’Neal’s gesture of solidarity. For both gestures together indicate a place we are going, places we have been, and the meaningful way we move through these spaces.

Daniel Bird Tobin

In the fall of 2018 I directed Angels in America, Part One: Millennium Approaches at Virginia Tech. During this process, Angels became the core filter through which I experienced all other art. Enter BlacKkKlansman.

These two pieces have significant dramaturgical similarities. They are both history plays about America’s recent past (using America in the same sense that Tony Kushner mostly uses it in Angels, to refer to the USA and not the American continents). They both ask what it means to be an American and who gets excluded. They both contain historical truth and fictionalized events. And importantly, they both reveal their creators’ perspective through a coda that jumps forward in time to examine the present impact of their historical stories. Nonetheless, those similarities in structure are used to convey radically different perspectives on America.

One of my favorite scenes in Angels has always been Act III, Scene 2 of Part One. Belize and Louis meet in a coffee shop for a hilariously poignant discussion, one ostensibly not about their sick friend Prior. These two men’s relationship has always had fissures, but those grow into chasms as the stress over Prior’s worsening condition leads them to a frank discussion of their own intersecting identities. The argument becomes increasingly explosive until Louis attacks, “You hate me because I’m a Jew,” and Belize rejoins, “You hate me because you hate black people.” Their disjunction is laid bare.

BlacKkKlansman uses Ron’s black identity and Flip’s Jewish identity as a source of unity. Early on Ron asks, “Why haven’t you bought into this?”, surprised at Flip’s reluctance to immerse himself in the KKK investigation. Ron sees Flip’s Jewish identity as a source of bonding, something to transform them into the “Stallworth Brothers.” Indeed, Flip later confesses, “I didn’t think much about it [my Jewish identity]. Now I’m thinking about it all the time.” The hate they experience from the KKK binds them together as friends and partners.

Seemingly then, Angels presents the identities of its characters as a pessimistic source of separation while BlacKkKlansman offers them as an optimistic source of alliance. That clean delineation is smudged in each work’s coda. In the Epilogue to Angels in America, Part Two, we jump forward five years from 1985/86 to the early 90s and see the core characters not only surviving but thriving. Belize and Louis still argue, but it feels more like bickering than animosity. The play’s final words of hope and triumph ring out from Prior, “And I bless you: More Life. The Great Work Begins.”

BlacKkKlansman couldn’t be more different. Its seeming triumph comes earlier when the investigation is mostly successful, the bombing targets saved, and the racist murdering and assaulting cop arrested. Then we jump forward to 2017 in Charlottesville. Nothing has changed. That triumph was a mirage. Racism, hate, and violence are at the forefront of America. The alliance meant nothing. The movie leaves us with the words of two people from the vehicle attack. In stark contrast to Prior’s “More Life,” the first person says, “There was a woman laying there, hardly breathing, and uh, they’re rolling her over, and she died.” Finally, in the last spoken words of the movie: “This is my town. We did not want the motherfuckers here.”

I desperately want the hope of Angels’ ending to be true. I want that triumph. I built it into my direction of the play. But how does my own identity filter that desire? As Ron tells Flip, he can pass as a “true white American.” Despite being the children of immigrants, I am instantly viewed as far more American than so many other true Americans because my parents came from a non-“shithole” country. This privilege is a filter that the reality of BlacKkKlansman disrupts and/or reveals, and I am left curious how my direction would have been different if BlacKkKlansman had been my core filter for Angels in America rather than vice versa.

Donta McGilvery

BlacKkKlansman educates audience members in the history of the Black Power Movement of the 1970s and 80s, and should be included in the curriculum for middle and high school youth. These lessons can be used to generate class discussions about race, racism, and the American Civil Rights movement.

My identity—as a black male, father, student, and educator—legitimatizes this response. BlacKkKlansman can educate youth of all communities about the Black Power movement in the United States in addition to the nonviolent movement of the 1950s and 60s. Young people of any ethnicity can benefit a great deal from learning this history, though the film can be especially rich for African American students.

History lessons are embedded into every aspect of the movie. Throughout, we hear names such as Angela Davis, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), Ahmed Sekou Toure, and Kwame Nkruma; African and African American revolutionary leaders about whom most students in K-12 schools have never learned. Students in the U.S. lack a complete understanding of both the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and African freedom movements. Knowing this history can help African American youth see their rich heritage and understand the fight and intelligence of our African ancestors. As with Lee’s earlier Malcolm X (1992), this film teaches lessons rooted in the African American experience not taught in schools.

Lee’s curation of essential African American names and movements opposes the negative false narratives attached to the Black Power movement and the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM). Using the true story of Ron Stallworth’s life, Lee draws a connection between the BLM movement of today and the Black Power movements of the 1970s. He illustrates how both movements, though in different eras, are seen by some as problematic. While watching the film, I realized that those who were upset about the phrase “Black Power” accepted a fictitious master narrative written by those who are not black and not forced to live within the demeaning conditions of many black Americans. That master narrative falsely suggested that Black Power is about hate and black supremacy. The film makes it clear that the phrase is one of black empowerment, as seen in the scene when Ron Stallworth is assigned to attend a rally in which Kwame Ture (formerly known as Stokely Carmichael) is invited to speak. The police force (and the Klan) have a problem with Carmichael’s presence and speech because they—believing the master narrative about the black movement—misunderstood his speech as hate-filled and anti-police. To these officers, Black Power is a call for black people take up arms against them. The officers saw Ture and his speech as a threat to their community despite Mr. Stallworth—a black man—informing his superior and colleagues that the speech encouraged black pride, not hate. The officers failed to understand this important message.

I have always known about the Black Power movement, but only that it was a radical and violent movement. Spike Lee’s movie help me to understand the movement in a much more positive light. As with Black Power messaging, today’s Black Lives Matter carries the same often misunderstood message of empowerment. For this very reason the movie should be used to teach students in middle and high school the need for movements like Black Power and Black Lives Matter. As long as some lives are being treated as less important than others (the mass incarceration of black and brown bodies and the murder of unarmed black bodies by police officers), there will always be a need to empower young black pupils. Having gained a new respect for the Black Power movement through this film, I will now empower youth using the film as a teaching tool. My hope is that you will as well.

Sabrina Treacy

When movies about blackness hit the theatres, I prepare for the differing reactions between my black and white friends, colleagues, and family members. As a biracial individual, I am situated in a particular demographic where the question of “how do you love your oppressor?” is as intimate as “how do you love your racist family members?” I have a lot of experience with difficult conversations about race in both black and white groups. Most of the time, when it comes to discussing movies about race, the result is the same: black people are usually despondent, and white people stunned and infatuated. As in the case of Driving Miss Daisy (Bruce Beresford, 1989) and Green Book (Peter Farrelly, 2018), this distinction did not change with BlacKkKlansman.

The majority of white people with whom I have spoken about the movie laud Lee’s work. I have heard from them that it was the best movie of the year, that everyone needs to watch it, and that the depiction of racism is one of the most powerful ever. The majority of black people with whom I have spoken about the movie find it to be dated, too amiable to the police, and failing at grasping the nuance of Black Americans. I err on the side of Black Americans.

The criticism coming from my black colleagues elucidates a complex review of BlacKkKlansman. The protagonist, Ron Stallworth, fills the difficult role of a Black cop in the 1970s who rocks an afro hairstyle and dresses like a character from a that era’s Blaxploitation films. Among Black audiences, a similarly-styled character would usually be celebrated for his crime-fighting style and engaging in Black cultural norms. In BlacKkKlansman, this characterization of Ron Stallworth seems a bit inauthentic. The only time the audience sees Ron having fun with other Black people is during the soul train line dance scene with the Cornelius Brothers and Sister Rose’s “Too Late to Turn Back Now” playing in the background. Other than this particular scene, Ron is rarely seen spending time with other Black characters, save the time he spends with his girlfriend Patrice. The rest of the movie, Ron is seen buddying-up with the other white policemen. enacting a certain archetype of the “token black friend.”

Because Ron is working from within the system to dismantle white supremacy rather than outside of it, he plays into the politics of black respectability and becomes the example of a “good black person” for the white audience. As Ta-Nehisi Coates and others have explained, for many Black Americans this is an exhausted narrative. A black colleague of mine expressed the sentiment that being a cop is automatically anti-black; meanwhile, a white colleague expressed reverence and admiration for Ron’s embodiment of a black, progressive cop. This narrative seems germane to their respective ideals of race relations in society, which is entirely antagonistic to the notion that the police force is inherently anti-black. These two antagonisms only deepen the racial divide.

These differing opinions have the potential to foster a genuine conversation about the extremely complex dynamics of race in America today. BlacKkKlansman and the differing reactions to it exemplify the continuing racial divide within the ideals held by diverse Americans. Bringing these different reactions to the forefront in cross-racial conversations may narrow the divide, yet BlacKkKlansman’s attempt to interrogate this divide resulted in a positively gratuitous film.

Isaac Kolding

Early in BlacKkKlansman, Ron Stallworth goes to a Black power rally to watch (and record) a speech by Kwame Ture. In his speech, Ture says, “When I was a boy, I used to go to the Saturday matinees and watch Tarzan all the time … White Tarzan used to beat up the Black natives. And I would sit there yelling ‘Kill the beasts, kill the savages, kill them!’… But what I was saying was ‘Kill me.’” White Tarzan, a film hero, taught Ture to hate himself.

If you want to quickly get to the political heart of a fictional narrative, a good question to ask is often, “Who is the hero of this story?” A character’s hero-status can be read as an endorsement of his or her politics and way of being in the world. BlacKkKlansman is concerned with the way that movies turn protagonists into heroes, and how heroes can become political or moral problems. At the beginning of BlacKkKlansman, scenes from Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939) are intercut with and transposed onto the figure of a racist orator. Later, KKK members cheer as they see their worldview validated onscreen by the Klansman heroes of the The Birth of a Nation (D. W. Griffith, 1915).

Near the end of the film, Patrice, Ron, and Ron’s fellow police officers collaborate to fire a racist police officer who had sexually assaulted Patrice. It’s a feel-good, Hollywood-ending scene, in which everyone bands together to defeat a baddy. If the film ended here, it’d be reasonable to think that the film is making Stallworth into a hero—the middle-ground figure who is able to facilitate cooperation between the police and black activists.

But the film doesn’t end there. In the next scene, Patrice asks Ron if he’s willing to resign from the police department, and he refuses. His hero-status is called into question by both Kwame Ture and Patrice. He is not a figurehead or the representation of a movement; he is challenged, torn. Patrice is about to leave Ron’s apartment (and Ron) when they both hear a knock on the door. Guns drawn, the police officer and the Black radical glide, side-by-side, down the hallway of Ron’s apartment building. Through a hallway window, a burning cross can be seen. Audio from documentary footage of white supremacists protesting in Charlottesville, Virginia, overlay a close-up fictive scene of a cross-burning—then the image cuts to footage of the actual 2017 “Unite the Right” rally; the fictional representation of the KKK blends aurally with the non-fictional portrayal of American white supremacists. The faces of these KKK members are obscured; a film about, among other things, the unmasking of white supremacists ends with images of masked fictional KKK members, which cut to the bare and visible faces of real white supremacists in 2017.

The white supremacists protesting in Charlottesville were in part rallying around a Confederate monument. Confederate monuments make the wrong kind of hero; like The Birth of a Nation, they claim that hatred deserves a place of honor. These monuments are claims about who viewers should root for—and, implicitly, who they should root against. Among other things, the Charlottesville white supremacists are depicted, at the end of BlacKkKlansman, in a corrupt, terroristic act of hero-making. By subverting a fictional happy ending with scenes of documentary horror, Lee calls into question the political usefulness of happy endings—and calls his audience’s attention toward the ways that films make heroes.

I don’t think that Ron Stallworth is a film hero—or if he is, he’s a qualified hero. BlacKkKlansman is too self-conscious and skeptical about the process of hero-making to give audiences the satisfaction of a Hollywood denouement. When Patrice is about to leave him, Ron asks to talk, to see whether the two can resolve their differences. But they never get a chance at real discussion. They are interrupted by a knock on the door—the presence of racist terrorism inserts itself into their conversation before they can resolve their differences. Despite Patrice calling Ron an “enemy,” despite her recognition that he falls short, when danger approaches she does not hesitate to stand with him. The last time we see them together is, perhaps, a pragmatic moment, and certainly not an image of heroic triumph: expressions tense and cautious, they ease forward, guns facing outward toward the danger.

Caress Russell

Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman is a brilliant look into the harsh realities of hatred and racism. Society often fails to recognize the separation between an individual’s course of action and their internal battle, while Lee illuminates the humanity within those who hate. In a world of black and white lines, BlacKkKlansman exists in the gray, exposing the intangible struggles with identity and acceptance. This movie is Lee’s attempt at facilitating the idea of tolerance and acceptance through real-world application, begging the question “is it our responsibility to interrogate our own ignorance with the hope of finding an epiphany?” Lee’s movie answers “yes,” while simultaneously concluding that one must also seek to understand that the journey toward a “broader perspective” is riddled with confusion, disappointment and uncertainty.

Acknowledgement that the journey is difficult for every person, regardless of which side they started on, leads us to a compassion that surpasses our feelings about an individual’s final decision or action. Lee is providing a blueprint for tolerance, through the expansion of a true story profiling the characteristics of hate and its reflections in modern society. He highlights the turmoil and indecisive nature of each of the characters, which allows the audience to connect in some way with their own hidden biases. BlacKkKlansman is a bold response to our secret internal battles, forcing us to come to grips with our own ignorance.

Examining racism is sticky and difficult. We often view negative speech as having an innate power to tear apart and destroy people and communities. This film highlights how hate brings groups together, how a common enemy and collective hatred is an invitation into a community. We see how that hateful speech is used as a recruitment tool and a foundation for like-minded individuals to congregate and push their common agenda. For some, the film is all too real, with racial slurs tossed around like spaghetti at a food fight, yet what we see on screen isn’t too far from what we’d hear within the private corridors of some of our nation’s elite spaces. Lee doesn’t hold back. He reveals what so many have thought, felt and battled with. He unites audiences around the notion that while we may get it wrong at times, we are all trying to figure it out. Simultaneously, he proves the power of speech and its transformation into action. The film concludes with a clip of President Donald Trump, leading us to question our current reality, reminding us that words have power and that the history we forget could very well be the history we repeat. BlacKkKlansman reminds us that tolerance is a journey requiring a leap, and that compassion must first be given before it is received.