Abstract

This article looks at multimodal literature, texts that deliberately activate visual and/or spatial elements making them covalent with the linguistic element, as texts that explore the limits and possibilities of print books as a medium. Using Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor by Lynda Barry, Tree of Codes by Jonathan Safran Foer, and The Silent History by Eli Horowitz, Russell Quinn, Matthew Derby, and Kevin Moffett as case studies, the relationship between the material aspect of the books, most often found in the multimodal elements, and their themes is emphasized. This metamedial study focuses on the materiality of books as a significant element in our interpretation that situates the book in broader discussions of media consumption today.

When I pick up a book, I anticipate the interior: what story will be told? How might the author deviate from the well-trod path of narrative? Will I enjoy this book? I rarely spend much time considering the material object in my hands beyond the quality or condition. But what does this medium offer to the reader? Is it a mere convenience we have allowed to become a de facto form? When we acknowledge the fact that, in addition to the eBook and Electronic literature, most media today can contain narrative, the print book becomes a significant choice. It might seem that the recent appearance of multimodal texts, defined here in as texts that deliberately activate visual and/or spatial elements making them covalent with the linguistic element, is an effect of contemporary technological and commercial innovations, but the technology to print and disseminate multimodal books considerably precedes their introduction to the mass-market. Authors such as William Blake, Laurence Sterne, Emily Dickinson, Ishmael Reed, and others used the legible visual and spatial well before current scholars came to define such books as multimodal. Now as there are more options for printing as well as for mediums that can present narrative, the form of the book needs to be better understood. By looking not just the medium, but also how it relates to the theme of the book, I hope to better show what multimodality can offer on its own and in tension with multimedia in contemporary American narrative.

The conventions of book design were developed around printing presses and have changed very little, even in eBooks, as technology has advanced. Though we have become used to reading based on these conventions, former technological constraints have influenced the standard, a block of text that spans the width of a page with only a margin, more than narrative clarity. Furthermore, the generic conventions of adult literary fiction place the text as the dominant element and subsume any images, photographs, typeface choices, or white space, among many other possible aspects, to secondary tools that serve the text, usually with the assumption that we should see through these material choices to the meaning of the words. Multimodal literature, which blends several semiotic modes in the narrative through the use of visuals, blank space, and inventive page layout, is often mistaken for multimedia, as it recalls the image-heavy forms we often find online, but books are a well-established medium that has existed for centuries; multimodal books are not attempting to reinvent or reimagine the medium, but to explore the possibilities of the book beyond conventions. What was once a technique in niche books such as artists’ books is now asking the reader to not just hear, but to see what is being said in the relationship of the medium to the book’s themes. To explore this, I will consider how we understand the definition of “medium” and look at three books, Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor by Lynda Barry, Tree of Codes by Jonathan Safran Foer, and The Silent History by Eli Horowitz, Russell Quinn, Matthew Derby, and Kevin Moffett, in this paper.

Despite the fact that the idea of the book appears obvious, it is difficult to find a concise yet encompassing definition of “book.” Currently we appear to be operating under the idea that we know a book when we see it. The question of what a book is is especially significant in the twenty-first century as literature now competes with and is influenced by many forms. These interactions can be understood through the convergence paradigm that Henry Jenkins outlines in Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide: “If the digital revolution paradigm presumed that new media would displace old media, the emerging convergence paradigm assumes that old and new media will interact in ever more complex ways.” 1 ) There are many ways to define medium. The most basic definition states a medium is “an intermediate agency, instrument, or channel; a means; esp. a means or channel of communication or expression.” 2 At the same time, truisms such as “all media is mixed media” 3 reveal the difficulty of simply defining medium in our convergence culture.

Our working conception of media has developed over time and has failed to account for all the differences of production today. This is especially important when forms cross or transgress previously understood borders between forms, just as we see with multimodal narrative books. 4 While multimodal books use visual and spatial elements, such as images, color, and white space, to cocreate the narrative along with linguistic text in a way that breaks convention, ultimately these books are still printed on paper and exist in the same physical format as other books. Scholars have sought ways to clarify and parse media, even when the media appear similar, that will help us in better understanding the book. Lars Ellström sets up useful categories in Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality: “Basic media are simply defined by their modal properties whereas qualified media are also characterized by historical, cultural, social, aesthetic and communicative facets. Technical media are any objects, or bodies, that ‘realize’, ‘mediate’ or ‘display’ basic and qualified media.” 5 There are several ways we can go about dissecting mediums, based on how we perceive the contents (whether through sight or sound), its cultural definition (for example understanding a photograph as different from a painting), or how we receive the content (on a television or in person). However, it is more important to address “the critical meeting of the material, the perceptual and the social” 6 to understand any medium. This meeting could also be called the “socially realized structures of communication,” 7 how we as a culture have come to understand a medium, that Lisa Gitelman introduces to the discourse.

In understanding how the elements of the book come together, we ultimately still place them on the same shelves in the same stores and anticipate a similar reading experience, though our expectations are sometimes exceeded or eschewed. Another way to think about the question of medium would be to consider “how the intrinsic properties of the medium shape the form of narrative and affect the narrative experience,” 8 as Marie-Laure Ryan does in Narrative Across Media. Overall, Ryan’s definition relies on the constraints and affordances, that is the limitations and possibilities, of forms in expressing narrative, rather than merely the conventions, which align more closely to considerations of genre that “purposefully uses limitations to channel expectations.” 9 “Genre conventions are genuine rules specified by humans, whereas the constraints and possibilities offered by media are dictated by their material substance and mode of encoding,” 10 therefore when we consider different media, we must keep in mind what is possible in their material form. Multimodal books have the same possible means of representation as other books, but rather than using the visual and the spatial solely in service to producing legible text, these books use the page in convention-breaking ways 11 to further our understanding of the book as a form and of each book as a distinct work of art.

At this moment, why does it seem significant to have books that rely on their presence as print texts and also make full use of the visual and spatial already inherent in the conventional print form? In large part, this has to do with anxiety about the place of literature in our changing media culture. Lanham provocatively asks this question in The Electronic Word:

Many areas of endeavor in America pressured by technological change have already had to decide what business they were really in, and those making the narrow choice have usually not fared well. The railroads had to decide whether they were in the transportation business or the railroad business; they chose the latter and gradual extinction. Newspapers had to decide whether they were in the information business or only the newspaper business; most who chose the newspaper business are no longer in it… For all its fastidious self-distancing from the world of affairs, literary study faces the same kind of decision. If we are not in the codex book business, what business are we really in? 12

Lanham is dealing primarily with literary and rhetorical studies, but his question holds true across aspects of production and reception of literature. At this moment, the question of what “business” authors are in is at stake: is literature joined to the material form of the book? Though I think multimodal literature is likely to continue in some way, just as authors engaged the visual and spatial in print books in the past, the current abundance of multimodal texts seems to be a reaction to our image-saturated culture and a desire to understand what the form of the physical book can contain and what benefits the codex, a paged physical book, can offer narrative.

Rather than being limited by conventions, multimodal books seek to explore the possibilities and restrictions of print books through awareness of the visible and spatial. To examine this idea, I will consider not just the multimodal elements of several works, but also the content and paratext, the material surrounding the narrative content of these works, to consider a potential metamedial relationship, as Alexander Starre does in Metamedia: American Book Fictions and Literary Print Culture after Digitization. Metamediality asks how we understand a book’s potential relationship with its material form. Starre suggests that we discuss not just books of fiction, but book fictions, in which the narrative and form work together, “interweav[ing] text, design, and paper into an embodied work of art.” 13 We can consider these books as signaling their purpose in being print books, through the narrative, text, design, and material components. This self-conscious relationship to form is present in three very different books I will take up in this essay to examine the codex and its limitations, benefits, and relationality: Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor by Lynda Barry, Tree of Codes by Jonathan Safran Foer, and The Silent History by Eli Horowitz, Russell Quinn, Matthew Derby, and Kevin Moffett. Through these projects, I want to more closely consider both what the material substance can offer and the content-interface dichotomy which Lev Manovich defines in The Language of New Media as “the connection between content and form (or, in the case of new media, content and interface) [that] is motivated; that is, the choice of a particular interface is motivated by a work’s content to such a degree that it can no longer be thought of as a separate level.” 14 These books are print texts not because it is the status quo form, but because the form can further our understanding of the project through its material presence.

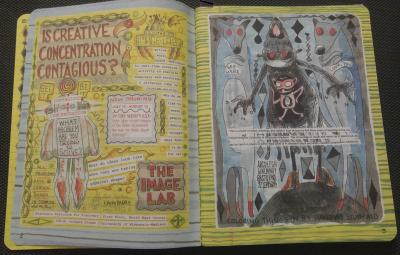

Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor (2014) is a non-fiction narrative 15 by Lynda Barry that recounts how she found herself teaching drawing and writing at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the relationship between cognition and the body. Though filled with images and drawings, it is much closer to an artist’s book, a book created as an original piece of art, than a comix: panels play little to no role in the pages, some pages feature text while others rely on images, 16 and the form of the composition book is present throughout. Regardless of its publishing classification, we should consider this text in terms of the self-conscious multimodal narrative, and specifically through Johanna Drucker’s definition of the artist’s book in A Book of the Book as “self-conscious about the structure and meaning of the book as a form” 17 in its material form and themes.

The marbled notebook runs throughout the narrative, from the statement on page three that these “notes, drawings and syllabi” were “kept by hand on pages of either legal pads or in standard black and white marbled composition notebooks” to the photo on page 199 in which Barry poses with her students and the composition notebooks everyone filled during the semester. The book’s design, such as the cover with rounded corners and cloth tape on the binding and the pages which show the lines of the ruled notebook, mimic this form. But what takes this beyond mimicry or nostalgia is the significance of the composition notebook to the text. Barry favors composition notebooks, and legal pads, for her own note-taking and sketching, and in the six courses she discusses in this book, she also requires the “standard composition notebook B+W marbled cover, 200 pages” 18 as class material for all of her students. Not only is it a facsimile of a composition book, but that form is constantly present in the text.

But why the composition notebook? Barry does not explain why she requires the composition notebook as opposed to another type of material, but rather than becoming fixated on this form, though it pervades the narrative, we should consider what Barry asks students to do with their notebooks and what purpose the notebook can serve. Barry’s project is about the relationship between cognition and the body, how we understand, and how images, not the visual representation but “something which feels somehow alive, has no fixed meaning and is contained and transported by something,” 19 move among people. It is through the practice of observing, collecting, and drawing that she believes we can begin to understand the concept of the image and more, “The only way to this is by making things. Thinking about it, theorizing about it, chatting about it will not get you there.” 20 Barry believes the process of creating is essential to understanding and that cognition does not occur in the brain alone but requires the involvement of the body. She explores and enacts this theory throughout her classes, asking her students to probe these questions with their composition notebooks as daily diaries, which become more than records of their lives, but places of deep thought: “the nature of note taking by hand. Thinking of one’s compbook as a place. The practice of developing a place not thing.” 21 Not only does this process involve allowing images to come alive through drawings that are not “thought over” or narratives that are not constructed, but it also returns to a state of play that Barry thinks most adults have lost:

Daily practice with images both written and drawn is rare once we have lost our baby teeth and begin to think of ourselves as good at some things and bad at other things. It’s not that this isn’t true, but the side effects are profound once we abandon a certain activity like drawing because we are bad at it. A certain state of mind (what McGilchrist might call “attention”) is also lost. A certain capacity of the mind is shuttered and for most people, it stays that way for life. 22

This is the crux of Barry’s project. By asking students to return to drawing, regardless of whether the pictures are “good” or “bad,” she asks them to open themselves up to new types of attention and thought. The composition notebook is a place for this practice of play, which in turn becomes a place for attention and serious thought.

Barry’s book does not explicitly state much of this: rather her book is the space in which she works through these ideas, as well as the experience of teaching courses that ask students to write and draw without the explicit goal of improving their skills at rendering. Thus, Syllabus is not just modeled after a composition book for the sake of material pleasure, but because Barry teaches from her own experience of writing and drawing. She asks her students to use the composition book not because it is superior to other notebooks or sketchbooks, but because it is an easily acquired, cheap form she has favored over the years (along with the legal pad) for her play. Syllabus is not Barry’s definitive theory of cognition and teaching; it is her place for deeply engaging with the ideas of memory, understanding, and image, just the sort of play she seeks to share with her students. What first seems like a clever nod to her teaching supplies is actually an enacted theory of “being present and seeing what’s there.” 23 Barry does not narrativize her teaching of this practice but enacts it for us in this physical book.

Syllabus is not just an “artist’s book,” it is the artist’s book in that it is Barry’s place for working. The physical form that relies on our connection to the medium of the book directly relates to the material she requires in her syllabi but also makes a strong link to her personal practice for over 40 years, which results in a strongly multimodal text. Furthermore, she enacts her process of working through, paying attention, observing, and collecting, which allows her to see what is there. The physical practice is the basis of her method, so a book effacing that practice, whether through the design, medium, or text, would be antithetical to her project. This explains not merely the overall design, but the handwriting and drawings throughout. Syllabus is replete with reasons it must be a physical book for the full idea to come through. It is also deeply self-conscious of the form, how the notebook functions for Barry and her students, and uses that to dictate its appearance and materiality, aligning it with the form of the artist’s book, though it has been reproduced into a fused medium and is not strictly a hand-crafted object.

To consider the form of the codex further, I want to discuss Tree of Codes (2010), a narrative exploring the potentials of multimodal books through removing portions of pages, rather than “adding” to the text through underutilized modes. Tree of Codes creates its story by erasure from Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz; words have been removed from the source text in order to create the new text. This manifests in die-cut holes, rather than black-out or white space as commonly used in erasure poetry and other similar projects. While it is also a reproduced work rather than a one-of-a-kind object, its printing was more intensive and despite being by a popular author and relatively well-received, it is now out of print. With delicate pages like lace, this project strongly resists manifestation in other forms and draws much of its power from its material presence as a print book.

The pages are what distinguishes Tree of Codes. The die-cut holes both erase and produce the narrative to create a book that is fragile and difficult to digitize. 24 It would seem the book must exist in the material form to maintain its identity and is frequently described as a “sculptural object.” Thomas A. Vogler focuses on “book-objects” or book sculptures in “When a Book Is Not a Book.” His essay delineates the book from objects that are concerned with the form but are best defined as not books, because “books have text and exist for the texts that they have,” 25 whereas these sculptures often feature no text or keep it from being read. However, we should not assume the “book” is simply whatever medium a text exists within. Vogler explains there is

an established sense of the book as a physical object that exists only, or primarily, to be the “container” of a therefore separable text… The “physical” production is separated from the “artistic” production, in a way that parallels the conceptual separation of the content of a text (which always points elsewhere to its meaning) and text regarded as material object. 26

Tree of Codes’s sculptural elements—the spatial design considers both the two dimensional, found in margins, spaces between words, and whitespace, and three dimensional, caused by several layers of die-cuts which often produce a hole seeming to bore through the pages—do not just surround or decorate the text, but create meaning. The desire to read meaning in the form is more strongly associated with visual arts than literature, and, furthermore, there is a tactile element to its presentation, but being like sculpture does not make it a book-object. While Tree of Codes interrogates the assumption of the container by using the physical form to create meaning in the text, it is a narrative that can and should be read rather than resisting reading or obliterating meaning.

Foer often writes about the absence resulting from the Holocaust and accommodating or reconciling this loss with life as the descendant of Holocaust survivors. Moving from his early works, such as Everything is Illuminated and “Primer on the Punctuation of Heart Disease” through Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close to Tree of Codes, we see Foer grappling with the narration of absence and how to discuss what cannot be present in his work. In “Primer on the Punctuation of Heart Disease,” he uses symbols to visually show non-verbal aspects of conversation used by a family rather than describe silence and pauses and in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close he integrates illustrations to limn the trauma of loss without words. But it is in Tree of Codes that the void is made manifest. These die-cut holes not only place the book solidly in the realm of print, but their presence forces the reader to confront absence at every moment, how it can make reality fragile and complicate meaning. The story, frequently referred to as “an enormous last day of life,” 27 is also interesting because of the source material. Foer cites Schulz as his favorite author, a Polish-Jewish writer who was shot by a Gestapo officer, and so the Holocaust becomes embedded in this choice as well. 28 Why is it necessary to not only make the absence physical but to do so through holes rather than another method? What does this relationship between content and form offer?

The text of the narrative is a very constructed work, and while it has a somewhat unearthly, unmoored quality to it, it also lacks many of the specifics or devices that one has come to expect in a story. Part of the reason it is described as “an enormous last day of life,” 29 as opposed to summarized is that the story proceeds slowly, with significantly more space on a page than words. The theme of absence is not only present in the material substance, but also in the story created by erasure. The protagonist has many encounters with “Mother” and “Father,” but it is unclear if either or both are physically present in the narrative, or just remembered. Father, in particular, seems to be struggling with unpleasant memories and loss: 30

Full of / vast / faded / mirrors, / our apartment sank / deeper / owing to / my mother, / endlessly / everywhere / discarded / . / sometimes / during the night we were awakened by / nightmares , / shadows / flew sideways / along the floor and up the walls / — / crossing the borders of / almost / . / hideously enlarged / shadows / attached to / my father / . / he would spend whole days in bed, surrounded by / Mother / . / he became almost insane with / mother. / he was / absorbed / , lost / , / in an enormous shadow / . / From time to time, he raised his eyes / as if to / come up for air, / and looked around helplessly, / and ran to / the corner of the room / . […] Then / he would fall / into / his thoughts / . He would hold his breath and listen. / He did not wish to believe / the / absurd. / But at night / The demands were made more / loudly, / we heard him talk to God, as if begging / against / insistent claims / . 31

Begging God, the father is made insane with Mother as if he has lost her and can neither forget her nor move on without her. Later, he says “ ‘How / beautiful / is / forgetting / ! / what relief it would be for / the world to lose some of its contents / !’” 32 Though it is not explicit, it seems that at least the mother who “could not / finish / her / almost completed / day” 33 is another present absent within the text and it is the memory of her that both keeps her from disappearing and tortures the father.

Tree of Codes seeks to discuss the continued loss caused by the Holocaust, that “reality is as thin as paper” 34 and can be easily destroyed, just as this book can be damaged. Books often address silence and absence, but this present absence cannot truly be a dearth because of its substance, in text and in material. Foer seeks to produce continuing absence through the die-cut pages. The fact that the source is by an author whose voice was silenced and lost during the Holocaust reinforces this. The material of Foer’s story complicates and underlines this absence, giving it form but also hollowing it out. In this way, the book becomes connected to the lost but remembered body. The three-dimensional form of the book is essential in producing this; it cannot exist in another format. Not only does the text need the physical manifestation, but it also allows the reader to contemplate the fragility of life and reality as if it were these pages you need to delicately turn. Furthermore, by connecting the book to the body through the source text, we also confront a voice who was lost to the Holocaust, examining the consequences of that genocide to us as readers.

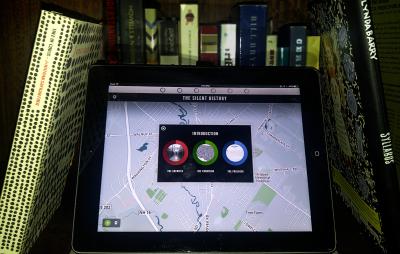

To ponder the inverse of what appears to be the situation in Foer’s Tree of Codes, I want to look at a text that was not originally a book and requires a crossing of media boundaries to explain its whole project. The Silent History by Eli Horowitz, Russell Quinn, Matthew Derby, and Kevin Moffett was first published serially via an iOS app in 2012. This born-digital narrative advertises itself as “a new kind of novel,” however, despite excitement about the potential of digital applications for storytelling, it was published as a print book in 2014. A potentially limiting move, the print book version no longer has two introductory videos and further loses parts of the original text, all the reader-submitted “field reports” based on GPS locations. The print book only retains the portion of the text written by Derby and Moffett called “testimonials.” While we could call the app multimedia because it uses video in addition to the textual narrative, the codex is definitely not multimedia and not consciously multimodal, seemingly abandoning the affordances offered by the app and further following conventions in the print book by using the text alone to tell the story. So, what could the story gain by this narrative migration?

The Silent History is, as mentioned, comprised of testimonials and field reports. Derby and Moffett wrote the main narrative arc, defined as the testimonials, and users can contribute field reports linked to particular locations that can only be read if you are in a precise spot. The testimonials follow several individuals who have intimate experience with “emergent phasic resistance,” the inability to comprehend language, such as parents, co-workers, medical professionals and those who were once a “silent” 35 themselves. Though the most innovative part of the project, the field reports are generally treated as supplementary because an individual would have to travel the world to read every one. Even the authors contend that the story, the narrative arc, exists solely in the testimonials and someone who is not near any tagged locations will not miss an essential part of the story. The print book reflects this information and does not refer to the field reports. For the most part, the print book appears to merely compile the testimonials in the codex form.

The claim to be a new type of novel seems overblown. Though the app does integrate location, it is an accompaniment to the narrative rather than an essential plot element. Amy Hungerford considers how this component of the app could change the interaction between the novel and the reader, moving it from a solitary and “place-less” object to an experience the user explores, thus changing how we understand readers. The field reports also become a place for interaction through the ability to submit place-based vignettes and grow the story. Hungerford ultimately considers the lack of “literary programmers” as the reason more “novel” apps do not exist, but I think the cause lies more in her ultimate conclusion in Making Literature Now: reading and literary production are about social connections more than genius or innovation. While apps and websites seek to build networks between people distant in geographical terms, physical proximity, material, and contact is most effective, “just as the lack of a physical book cover narrows the conduits for artistic vision, the lack of human physicality radically narrows the tools for social connection.” 36 An author or app developer cannot manufacture community by asking people to move themselves but continue to read alone.

The failings of the “revolutionary” Silent History app to change reading and readers does not explain its move to the physical form of the book though. The app could have easily been forgotten or become defunct, but instead it became a physical bound book. This suggests Horowitz et al. saw something to be gained in this move that was not achieved by the app alone. To consider thematic motivations, I will use Hungerford’s method in looking at The Silent History: to “take the form and content of a work to reflect, or even to allegorize, the deep structures of the historical moment in which it is made.” 37 However, I will apply her method to the project encompassing the book and app, rather than one or the other, by first walking through the content.

The narrative is centered around “emergent phasic resistance” (EPR), a virus people contract prior to birth that causes the language-processing regions of the brain not to function. These children are born with the ability to hear and make sounds, but they cannot understand verbal or written language in any form. Initially, the general public assumes these children have no way to communicate and will live isolated and detached lives and therefore the government should corral the “silents” rather than parents and doctors attempting to educate or study the affected. After some time, a school teacher discovers silents engage with each other through a complicated system of subtle face movements, called micro-expressions. Communities start to blossom for the silents, often in abandoned buildings or other liminal spaces. Tensions grow as people see these communities as threatening in their seclusion from mainstream society and because it is unclear how these young people provide for themselves. As hostilities come to a head and it seems unlikely the public will allow these communities to exist on the fringes of mainstream society, a doctor develops a new technology prompting the language-processing areas of the brain to function in EPR patients. This implant immediately becomes popular and the majority of silents have the surgery to be able to use language; the procedure even becomes mandatory in children under the age of seven. There are some obstacles, but overall the new technology seems to be positively increasing the ability of silents to integrate into society. While this technology appears as the ultimate solution for EPR, there are some silents who are resistant to getting the surgery, and prejudices against people who chose this life only increase. Ultimately, a lone renegade causes the implants to all malfunction for an unknown length of time. There is rioting and general chaos, especially by children implanted at birth, experiencing a lack of language for the first time. The imminent danger is resolved, but the narrative ends without resolving if the implants are restored to full functionality or even used at all. Ultimately, the general opinion about this technology seems to be ambivalence and the reader is left uncertain whether it was the best solution. This narrative arc parallels The Silent History as a textual object—as a new type of technology the app was unable to displace the familiar form and left the reader unsure about the introduction of this “new type of book” in the first place.

The book is a status quo form for the story, offering community of many different types. Horowitz and Quinn developed the app to build networks around the novel, encouraging readers not only to visit new locations to find more of the narrative through field reports but also to add to the story in a visible way. However, the app Silent History did not dramatically change how we read; there was no violence or chaos associated with this technology, but it also did not supplant the book. Instead, we see The Silent History return to the older technology in the form of the book and the reader who encounters both is left feeling ambivalent about the project of the app if the codex seems sufficient to contain the narrative and create community in the way books have since at least the twentieth-century. Not only do the themes of the story ask us to question our assumptions around technology, but also how supposedly innovative technologies may not actually improve life. Rather than solving a problem, whether how we interact with stories or how people engage without language, the technology seems to find a problem where there may not be one.

When we consider the full publication history, both the app and book together instead of as alternate or opposing forms, we can consider if our relationship to technology and how our information-driven society seems to look to the new and innovative as saviors over older models are the issues being questioned. I must admit the ending is ambiguous; it is not a resounding victory for either side, but we can conclude that the order of the project seems to be in favor of the continuation of the book, 38 despite its formal limitations and the conventions that this project then adheres to in its transfer across media. Though the idea that some people may be able to find meaningful existence without language is left open at the end, the authors identify language or sign-systems more broadly as the orienting technology in our lives. We are able to see language as how we create community and come to know ourselves and our world. The form of the book, whether the traditional or “new type,” is barely mentioned in the narrative, but the return of The Silent History to the traditional codex form ties this physical medium as a useful form that co-exists with newer media to the themes of the story.

Syllabus, Tree of Codes, and The Silent History all offer different reasons to exist in the form of print, but it is also undeniable that each has its own relation to the medium. Likewise, while we tend to think of the paper codex as limiting, it does not offer only one possibility for narrative, especially with experiments of multimodality. In Syllabus, the form of the book not only reproduces Barry’s work personally and in the classroom in understanding cognition and physical production, but the material substance underlines Barry’s embodied practice. Foer uses the form of the book to make absence present without negating its lack through language in Tree of Codes. While these two books explore their relationality and the possibilities of the codex, The Silent History allows us to consider how the book as a technology has not been superseded by newer technologies and how language and community function around these mediums. It also shows the limits of the book without multimedia: the ambivalence about technology would not come through as a theme without the full transmedia project. Thus, the physical form can enact practice, make real an idea, and underline themes through the material object. By remaining in the technical medium of the paper-based codex and using the cultural delineation of literature, narrative, and novel, it is clear that these books are exploring outside the conventions of genre, but without radically crossing media boundaries. We may not be solely in the “codex book business,” though fears of the “death of print” appear to be overblown as print books continue to sell and eBook sales are in decline, 39 but we have more to explore in terms of the true possibilities and limitations of the medium rather than staying within the conventions of either traditional books or literary studies. As other forms of storytelling proliferate, and digital technologies continue to make things newly possible, we may see this trend of strongly multimodal literature continue or we may realize it as a transitional moment exploring the strengths of individual forms. Most significantly though, by turning our focus to the materiality of books, we can consider how narrative occurs in the metamedial relationship as well, rather than in the words alone.

Bibliography

Alter, Alexandra and Tiffany Hsu. “As Barnes & Noble Struggles to Find Footing, Founder Takes Heat.” New York Times, Aug. 12, 2018.

Barry, Lynda. Syllabus: Notes From an Accidental Professor. Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2014.

Cain, Sian. “Ebook sales continue to fall as younger generations drive appetite for print.” The Guardian, March 14, 2017.

Clüver, Claus. “ ‘Transgenic Art’: The Biopoetry of Eduardo Kac.” In Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality, edited by Lars Elleström, 175-186_._ New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Drucker, Johanna. “The Artist’s Book as Idea and Form.” In A Book of the Book, edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay, 376-88. New York: Granary Books, 2000.

Elleström, Lars. “The Modalities of Media: A Model for Understanding Intermedial Relations.” In Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality, edited by Lars Elleström, 11-48. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Foer, Jonathan Safran. Tree of Codes. London: Visual Editions, 2010.

Gibbons, Alison. “Multimodal Literature and Experimentation.” In The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature, edited by Joe Bray, Alison Gibbons, and Brian McHale 420-34. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “Combining Close and Distant Reading: Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes and the Aesthetic of Bookishness.” PMLA 128, no. 1 (January 2013): 226–31. http://www.jstor.org.uri.idm.oclc.org/stable/23489282.

Horowitz, Eli, Matthew Derby, and Kevin Moffett. The Silent History: A Novel. New York: FSG Originals, 2014.

Horowitz, Eli, Russell Quinn, Matthew Derby, and Kevin Moffett. “Silent History.” Apple App Store, Vers 2.4 (2012). (https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/the-silent-history/id1034208751?mt=8).

Houston, Keith. The Book: A Cover-to- Cover Exploration of the Most Powerful Object of Our Time. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016.

Hungerford, Amy. Making Literature Now. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press, 2006.

Lanham, Richard A. The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.

“medium, n. and adj.” OED Online. Accessed 8 March 2019. Oxford University Press, www.oed.com/view/Entry/115772

Mitchell, W. J. T. Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Rajewsky, Irina O. “Border Talks: The Problematic Status of Media Borders in the Current Debate about Intermediality.” In Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality, edited by Lars Elleström, 51-68. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Rapatzikou, T. “Jonathan Safran Foer’s Tree of Codes: Book Design and Digital Sculpturing.” Book - Material - Text 1 (2017): 41-52. doi:10.13154/bmt.1.2016.41-52.

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling. Lincoln, NE: U Of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Starre, Alexander. Metamedia: American Book Fictions and Literary Print Culture after Digitization. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2015.

Vogler, Thomas A. “When a Book is Not a Book.” In A Book of the Book, Edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay, 448-66. New York: Granary Books, 2000.

Footnotes

- Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York: New York University Press, 2006), 6.

- “medium, n. and adj.”, OED Online, (https://www-oedcom.uri.idm.oclc.org/view/Entry/115772?redirectedFrom=medium)

- W.J.T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 5.

- Forms that seem to exist between media are intermedia forms. “Intermediality in the narrower sense of media combination… includes phenomena such as opera, film, theatre, illuminated manuscripts, computer or Sound Art installations, comics, or, to use another terminology, so-called multimedia, mixed-media and intermedia forms” (Rajewsky 55). While this definition appears to suggest that intermediality can also be considered multimedia, Rajewsky uses the term to signify forms that rely on a single form of technology, such as the book. Another way to think of this is as the potentially mixed media being “fused” (Clüver 180). This is a good way to think of the multimodal book, because while we look at it and imagine someone drawing, taking a photograph, or otherwise contributing a different “medium” to the linguistic text, “Each of the pages in the printed edition of [a] book is essentially a single illustration—a combination of text and imagery broken down into pixels too small for the eye to see—that has been etched onto an aluminum plate… and printed in an offset lithographic press… when we read a book’s text, we are looking at a picture too” (Houston 237).

- Lars Elleström, “The Modalities of Media: A Model for Understanding Intermedial Relations,” in Media Borders, Multimodality and Intermediality, ed. by Lars Elleström (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 5 (italics in original).

- Elleström, “The Modalities of Media,” 13 (italics in original).

- Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New: Media, History and the Data of Culture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 7.

- Marie-Laure Ryan, Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (Lincoln, NE: U Of Nebraska P, 2004), 1.

- Ryan, Narrative across Media, 19.

- Ryan, Narrative across Media, 19.

- Multimodal books are not attempting to replace traditional books or invent a new form, but rather fully explore the capacities of print beyond the traditional conventions of literary narratives. Furthermore, other scholars dealing with multimodality often note when a text is not only multimodal but also multimedia, a distinction that would be unnecessary if we could easily assume all multimodal texts were multimedia. For example, Alison Gibbons cites The Nambuli Papers as using “both multimodal and multimedial means in its hoax” (432) as it includes not only two books but also a DVD and board game in the boxed set in “Multimodal Literature and Experimentation” in The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature.

- Richard A. Lanham, The Electronic Word: Democracy, Technology, and the Arts (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 8.

- Alexander Starre, Metamedia: American Book Fictions and Literary Print Culture after Digitization (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2015), 6.

- Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 67.

- It is classified as a “graphic novel” in its paratext.

- Though there is clearly an interconnection in these elements it functions more as a call-and-response than a seamless duet.

- Johanna Drucker, “The Artist’s Book as Idea and Form” in A Book of the Book, ed. by Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay (New York: Granary Books, 2000), 378.

- Lynda Barry, Syllabus: Notes From an Accidental Professor (Montreal: Drawn & Quarterly, 2014), 48.

- Barry, Syllabus, 15.

- Barry, Syllabus, 72.

- Barry, Syllabus, 194.

- Barry, Syllabus, 115.

- Barry, Syllabus, 4.

- N. Katherine Hayles discusses this at length in her PMLA article on Tree of Codes. This does not make digitization impossible, in fact Hayles does find a system that allows her to scan, code, and usefully parse the text, but it is interesting that this book seems to not only signal its materiality, but protect it by being difficult to digitize or transfer.

- Thomas A. Vogler, “When a Book is Not a Book” in A Book of the Book, ed. by Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay (New York: Granary Books, 2000), 448.

- Vogler, “When a Book is Not a Book,” 449.

- Jonathan Safran Foer, Tree of Codes (London: Visual Editions, 2010), 11.

- Foer, Tree of Codes, 138.

- Foer, Tree of Codes, 11.

- This notation style attempts to show how Tree of Codes creates its text “with the slash indicating the holed-out or die-cut spaces between [words].” I have adopted this notation from Tatiani G. Rapatzikou, with the addition of paragraph breaks for page breaks.

- Foer, Tree of Codes, 23-28.

- Foer, Tree of Codes, 48.

- Foer, Tree of Codes, 44.

- Foer, Tree of Codes, 67.

- Throughout the book, those who have EPR are called “silents” or “the silents.”

- Amy Hungerford, Making Literature Now (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 77.

- Hungerford, Making Literature Now, 94.

- We can look at language in the narrative to be sure the technology in question is not our sign system. Several characters share the concern that micro-expressions may be superior to language because of the instability of language, “We were on the verge of understanding that words were waterlogged boxes—unsuited to contain the meanings inside. With the true language, intention and meaning and expression are all one” (86). This lingering uncertainty about language opens a space to consider how other systems might work, but ultimately language is neither decided for or against and it seems silents will be able to live in their own communities though potentially always in tension with those who see them as deficient. However, when the implants malfunction, losing language is a terrifying proposition. Calvin Anderson, one of the first people diagnosed as a silent and the first person to receive the implant said “My ears rang and I felt like my head has split open and all the words I’d ever learned were streaming out onto to the ground. It was the pure, grinding sensation of losing my mind” (410). Language is how we think and not only does Calvin equate losing language to losing thought, but to going insane, despite the fact that he only acquired the ability to process language as a form of communication later in life. Furthermore, when Dr. Burnham discusses the effects of the implants malfunctioning he confirms “My vague sense of the possible effects of a sudden absence of language was validated by some early news reports—a vertigo-like disorientation, a perceived distortion of space and time, and a hypersensitivity to certain sounds” (416). While the narrative would seem to be attacking language, ultimately the book relies upon language to exist and appears to be agnostic about what sign-system might be best. Rather, it is technofundamentalism that is under consideration, which is ironic because the authors themselves appear to have fallen prey to that in thinking that a new type of book was needed.

- See, for example, Sian Cain, “Ebook sales continue to fall as younger generations drive appetite for print,” The Guardian, March 14, 2017, and Alexandra Alter and Tiffany Hsu, “As Barnes & Noble Struggles to Find Footing, Founder Takes Heat,” New York Times, Aug. 12, 2018