Game live streaming has become popular in the past decade, with individuals participating in live streamed games as players and audience members, even as other forms of media and entertainment have moved to asynchronous and on demand formats. During the initial waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US, the importance of liveness and participation online increased as many strived to stay home as much as possible and limit in-person interactions. HQ Trivia is unique with its combination of being an online, live trivia game with simultaneous interactions during the game and asynchronous social media interactions. In order to participate, players need to conform to the game’s liveness. The liveness and shared experiences help create temporary communities of players who also interact on Twitter and Instagram asynchronously. The liveness aspect of HQ Trivia reflects earlier forms of shared mass media experiences. While a community of players was created and maintained by the game, HQ Trivia is part of the digital capitalist economy and is tied to the idea that leisure time must be productive. During the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, HQ filled one of goals of social media by capturing and diverting people’s attention. While HQ Trivia closed in February 2020 due to lack of financial capital, it returned in March 2020 during the first wave of COVID-19 using a neoliberal model of charity to increase participation and its social media presence. During the first waves of the pandemic, the combination of liveness, the chance to win money, as well as live and asynchronous interactions with hosts, boosted HQ Trivia’s audience to numbers that reached the game’s previous height of popularity in 2018 and 2019. Comments by the hosts and by players in HQ Trivia’s live chat, as well as connected asynchronous social media, reflect US culture, including the positive and negative dimensions of social media. What is said and not said by participants, hosts, or the company provides additional insight on US culture. Liveness may continue to be important in the concurrent age of on demand streaming and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

HQ Trivia: A Neoliberal Entertainment of Trivia, Liveness, and Social Media

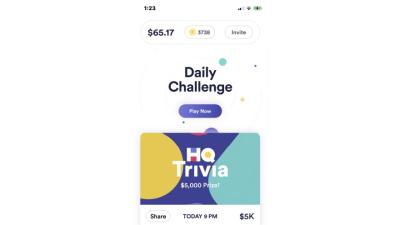

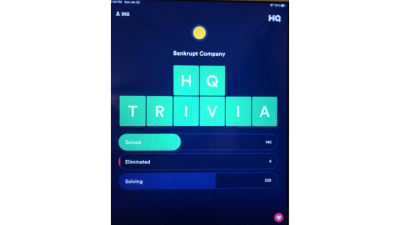

Created in 2017, HQ Trivia (HQ) is a streaming, live game that combines both synchronous live chat and asynchronous social media content. Twitch is the best-known example of a platform that combines both live gaming and live chat, offering individuals different affordances and audience engagement through cross-platform, social media connections. While HQ & Twitch share many similarities, they also have key differences. HQ only has one channel, which is trivia, and it is only available for a limited, set time at 9 pm Eastern US time. HQ requires its players to conform to its structured time, 1 rewarding players for following its liveness, 2 and can only be played on mobile devices. Within HQ there is no audience-only mode of interaction; either a person is playing (for money or non-monetary in-game rewards) or they do not participate. HQ consists of twelve, timed questions, with the game becoming more difficult as a player advances, so that the player’s skill is a factor in their success. 3

As a trivia game HQ offers players entertainment and a form of self-improvement and achievement in a neo-liberal model, 4 in which leisure time needs to be productive. If a player answers the twelve trivia questions correctly, they win a share of the prize money, which is split among all the winners. Since 2020, the prize amount has remained stable at $5,000. From 2017 through 2019, HQ offered prize amounts that varied depending on the day and theme of the game, with HQ games connected to specific brands such as movies or sneakers having the highest monetary rewards. 5 Players are knocked out of the game if they answer a question incorrectly, however they may rejoin the game once after elimination if the player has an extra life, which they can earn though in-game rewards or purchase in the app prior to the game start. Seeing the number of people who are eliminated while a player is still in the game can be a source of excitement. 6 Winning money is often not as important as a sense of accomplishment for the players. 7 Players of HQ and other live trivia games enjoy the anticipation of winning, even if they do not win. 8

With monetary prizes that are small when divided by the number of players, why do people play? The reasons why people keep playing games online may be educational, inspirational, for entertainment, or for a sense of community. 9 Players can have a sense of achievement in winning HQ or from progressing further than other players, gaining an understanding of the game’s mechanics, and the ability to boast online, both in the game and in other social media, as well as bragging offline. 10 Players of HQ develop a sense of affection for and connection to the game, creating an affective capture for the live game platform. 11 Part of the game’s attraction is that it is both competitive and entertaining concurrently. 12 Players can learn new information by participating in the game, and even when watching the game after being eliminated. 13 Online trivia games like HQ may also be popular due to their ease of playing. The rules are simple, there are a limited number of choices per question, and it is easy to gain access to the game on mobile devices. 14 Integration with other social media such as Twitter and Instagram and the chance to win money encourage users to stay connected to the game. 15

At the height of its popularity in 2018, HQ had between one to two million players per evening game. It was considered popular enough that SHRM (Society for Human Resource Management) felt it deserved an article discussing employee policies regarding non-work-related activities during work hours. 16 A factor that made HQ unique was its combination of trivia, liveness, and large numbers of people playing simultaneously. HQ was so popular in the US that other online live trivia games followed, but none gained the same audience as HQ, with Facebook ending their live trivia game in 2019. 17

HQ offers interactions among players and between players and hosts. These interactions help create an informal online community. Players in HQ are able to chat live while playing. 18 In keeping with HQ’s links to liveness, the chat within the app only becomes active five minutes before the game begins and stops soon after the game ends. Interactivity before and during the game, as well as the host’s live responses to the game and the chat, help reinforce the liveness of the game for players and create a sense of community, 19 even if it is only for a few minutes. Continuing to chat in response to the host and the quiz questions keeps players engaged after their chance to win is over. 20

HQ is connected to asynchronous interactions with the game, hosts, and other players on social media platforms, primarily Twitter and Instagram. 21 This can include responses to HQ hosts’ messages, such as “show me pictures of your pets,” and messages about an upcoming game from HQ, or messages posted by players, which include the hashtag #HQ or #HQTrivia, enabling others find them. Talking about the game or interacting with other players, the game, or the hosts helps people feel connected to the game and increases the sense of shared interests. One well known type of asynchronous social media posts by HQ players are videos of a player’s reaction to winning the game, sometimes even if the amount of money won is small. 22 This user-created content then helps promote HQ, increasing the player’s social media presence, and is a form of aspirational labor. Within HQ, highlighting wining players helped maintain interest in HQ. Some highly successful HQ players, primarily those who had won large prize money elimination games, were selected to be co-hosts or to make guest appearances. The video clips of players winning, submitted to HQ via asynchronous social media, are sometimes played in the minutes leading up to the game as part of the pre-contest period when the app is active. These videos not only provide entertainment, but also act as an enticement for people joining the game as they may also become a winner whose victory is shown to the HQ audience.

In the live chat during games players often referred to themselves as members of a unique group. The community of regular HQ players both in the chat and in other social media are referred to as HQties, 23 which is pronounced H-cuties. In-jokes, as well as words and phrases only known and understood by players of HQ, help make individuals feel like they are member of that group 24 and are a way to communicate a sense of community. 25

Part of HQ’s popularity comes from a lineage of trivia games and quiz shows. In the US, quiz game shows started on the radio in 1938. 26 Trivia is now a well-established part of popular US culture. The tv quiz show Jeopardy began in 1964 27 and still is on air. The Trivial Pursuit board game has been published in seventeen languages and sold over 100 million copies since 1979, and in-person trivia quiz games are held in bars, pubs, and restaurants. 28 Trivia games are popular, in part, because of the many different memories that the questions bring to mind, rather than relying on memorized information. 29 To answer trivia games, people rely on their episodic memory of experiences that happened to them, rather than semantic memory, which is long-term memory that is not directly connected to a person, like memorized dates and facts. 30

HQ draws on the familiar as well as the new, factors which may have influenced its popularity. HQ incorporates viewers neophilic interest in new things, it being a live trivia game with many players, as well as their neophobic tendencies. 31 The “exposure effect,” first identified by psychologist Robert Zajonc, found that people preferred things that are familiar. 32 Once you are familiar with a game or an app, you are more likely to prefer it to something new and unfamiliar. A factor in why people prefer things in which they are fluent and are familiar is it reduces the effort of choosing. 33 At the same time, people want to be challenged to think a small amount in ways that are familiar to them. While they want to learn, they also want to do so in ways that are not too challenging. 34 This can explain the continued interest in HQ, as people are challenged to learn more by playing, but in a low stakes environment.

However, over-familiarity can also decrease interest in an activity or media. 35 This could be why, after three years, the number of HQ players decreased dramatically from several million to between 50,000 to 60,000 players per game before HQ temporarily shut down for six weeks on February 14, 2020. No longer being the new thing, interest in it declined. HQ Trivia relaunched on March 29, 2020 during the unusual circumstances of the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, at which time it found an audience craving liveness and a sense of being with others. Since March 2020, HQ has tried to keep its players through new themes and features and the neoliberal addition of donations to charities

HQ Trivia: Reflecting the Positive and Negative of Social Media

HQ’s live interactions and social media affordances are unique when compared to other trivia games. HQ has two ways players can interact: a live chat prior to and during the game, and the asynchronous social media presence for hosts of HQ and the platform itself on Twitter and Instagram. In the live chat feature of HQ, people discuss the same issues they do outside of the game, as individual’s offline lives are not separate from their online lives. Each live chat message is only visible for several seconds before it is moved offscreen by newer messages. The live chat content can be divided into six broad categories: Group Membership; General Social Messages; Comments on Current and Ongoing News and Sports; Promoting Political or National Views; Positive Attention Seeking; and Negative Attention Seeking.

Group Membership live chat messages are primarily in-jokes that help establish a player’s knowledge of and membership in the HQ community. The most commonly seen Group Membership chat messages include the phrase “Bird’s Nest Soup,” a reference to an infrequently recurring question which a majority of players guess incorrectly the first time they see it, 36 or “Reggie,” the name given to a video of a black bear eating dandelions who is considered the game’s mascot. 37 This video clip is often shown during games. Other Group Membership chat messages include player-suggested corrections; comments on the questions and answers; laughing at guest co-hosts who are not part of the “in” group and mispronounce “HQties”; and suggestions for future theme games. By creating these public comments that use in-jokes and HQ-specific phrases, players demonstrate their membership in this community. 38

General Social chat messages tend to reflect a person’s situation, location, or mood. Examples include: “Hello from Hoboken,” “Happy Thursday,” “Love the snow.” This is similar to posting an update on other asynchronous social media. Current and Ongoing News and Sports chat includes messages such as “Go Jets!,” “Remember to Vote,” and “I hope everyone in the hurricane’s path stays safe.”

Promoting Political or National Views chat messages can include words and sentences, as well as flags and other emojis. In the weeks before and after the 2020 election, people posted messages for specific candidates, with the shorthand of “45” used for Trump and “46” for Biden, as well as the slogans for the two different campaigns and the US flag. Flags emojis can also be used in the chat to show solidarity with another country, especially if that country is in the news, due to a positive event such as winning a sporting tournament, or a negative event, such as a natural disaster. In such cases, either hearts or the praying hands emojis are often included with the flag image. After a country is mentioned in a game, some players will respond in the chat with that country’s flag.

There are two types of Attention Seeking chat messages: positive and negative. Positive Attention Seeking chat messages include content such as “It’s my birthday,” “I got a job,” “This is my favorite part of the day,” or, after the game is over but the chat is still active, “I won!” Negative Attention Seeking chat messages may be directed at HQ or the host or attempts to get others to reply. Online harassment and bullying are forms of affective capture 39 and can be as much of a draw as the game itself. Examples of negative messages directed to the host or the game include complaints about the game starting late and negative suggestions as to why the game is late, such as drug use or laziness; complaints about the infrequency of themed games; complaints about changes in the frequency of games; or negative comments about the host’s comedic ability. Negative emojis used in these messages include the clown and poop emojis. The use of images, including emojis, to harass or gain negative attention is more likely to be directed at those who are considered racial/ethnic “others,” in addition to people who are identified as LGBTQ+ or people with disabilities. 40 In the past year, other Negative Attention Seeking messages include disparaging comments about COVID-19 vaccines or vaccine mandates, although the short amount of time a message is visible and the limited character count mean that in-depth misinformation is not easily conveyed in the chat.

Emojis are used in almost every category except for chat messages about Group Membership. HQ relies on bots, automated software which identifies objectionable comments, as well as paid staff to monitor the live chat. During the live chat, HQ community members also identify and object to unwanted behavior, a form of self-policing, similar to the self-policing within Star Trek fan fiction communities described by Jenkins. 41 But self-policing cannot eliminate all negative behavior online.

As with other social media, incidents of racism and sexism occur on HQ in the online chat, as well as hosts’ other social media channels, although such acts are limited by restraints placed on what can and cannot be posted. HQ’s live chat and social media posts offer a way to examine what larger and complex issues in US culture are discussed and how these issues are expressed by players and the company. Like the internet as a whole, social media and live gaming platforms reproduce and reinforce power relations in society as a whole regarding gender, sexuality, and race/ethnicity. 42 One example is the frequent negative chat reactions to a video clip of Oprah Winfrey shown during some games. Oprah Winfrey is such as powerful symbol in the US that her last name does not have been included for people to know who she is. 43 Public, negative commentaries of Winfrey in media are often gendered 44 and based on race. 45 Being well known as a celebrity or social influencer can make a person a target for online hate and harassment. 46

The video clip is a surprised reaction shot of Oprah during the Prince Harry and Meghan Markle interview in March 2021. The video is played in-game when large numbers of players guess an incorrect answer. The first time the Oprah clip was played, the reaction in the chat was swift and it was almost all negative, which also provides a demonstration of the liveness aspect of HQ. Chat messages with the name Oprah followed by either the clown or poop emojis were initially most common. Other players immediately objected to the negative comments in the live chat and asked for those comments and players to be removed. It took several days before the messages with those emojis no longer appeared, as the chat monitoring began to block those comments. In response to the chat monitoring, new negative chat messages regarding Winfrey started when the video clip of her was shown. The new messages had her name and a cow emoji or comments about Winfrey’s weight. Other messages said Winfrey had eaten Reggie the Bear, the mascot of HQ. Fat shaming and weight stigma often have racists aspects 47 with overweight black women being considered “gluttonous” 48 due to their ostensible lack of restraint of their appetites. 49 This stereotyping of Black people and gluttonous behavior can be traced to European discourse in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. 50 While it would be easy to assume that online harassment such as this is due to online male geek masculinity, such assumptions ignore the rampant racism and sexism that are part of the larger US culture. 51 Those who posted the negative messages about Winfrey were also producing affective labor based on others’ reactions about their posts in the chat.

The subjects not discussed on HQ, by its hosts or on the company’s official social media accounts, can also be important to examine. On December 16, 2018, the accidental death by drug overdose of Colin Krool, one of the co-founders of HQ, was not mentioned in any of the HQ’s social media channels or the live game. 52 This may be a reflection of the avoidance of discussing death and expressing grief in US culture, 53 even though the death was discussed on social media in general. However, on the third anniversary of Krool’s death in 2021, the host mentioned at the end of the game that it was a sad anniversary for HQ, mentioned Krool by name, and offered information about drug treatment hotlines. It may have been discussed in 2021 because enough time had passed that it was considered appropriate, or it may have been motivated by the COVID-19 pandemic, either because of more public recognition of death in general, or because of the increase in drug overdoses during the pandemic. 54

Political events are not discussed by hosts during HQ or on its other social media platforms. A sign of the commonness of mass shootings in the US is that these events are also not mentioned by the hosts. An exception to this was after the mass shootings at multiple locations in Atlanta, Georgia at Asian American owned businesses in March 2021. After that night’s show, the host offered his condolences to members of the Asian American community in Atlanta and in the game the following evening, HQ offered information about organizations working against Asian American racism and discrimination, as part of the larger social media #StopAAPIHate campaign. It is also notable that neither the host nor HQ official channels discuss any racist, rude, or sexist comments which are made in the HQ chat or on other social media platforms, even when such comments are visible in the chat to players.

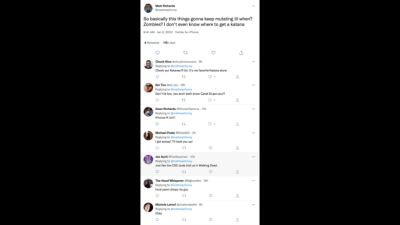

The asynchronous social media presence on Twitter and Instagram of HQ and HQ hosts is another way HQ blends live trivia and social media. The first host, comic Scott Rogowsky, said that during the time that he hosted HQ, aside from the daily jokes he posted on Twitter, most of his tweets were about HQ or interacting with HQ players. 55 HQ’s current main host, comic Matt Richards, is also active on Twitter. Most of his tweets fit within five categories: information about himself and his life, including his family; stories about his pets; comedy show announcements; information about HQ when it’s close to game time or there are technical difficulties; and funny remarks or general opinions. HQ players post replies or comments directed to him with game screen captures or other game related comments, but his humorous remarks often get the most responses, as other Twitter users play along with funny replies.

However, negative social media posts are also directed to the hosts of HQ. These messages are often a reply to a Tweet or an Instagram post, using racist or hateful language but substituting a symbol for some of the letters in order to evade easy moderation detection. As part of the neoliberal influence on social media, it is considered primarily the role of social media users and not platforms such as Twitter or Instagram to ignore, stop, or reduce negative or hateful messages, with moderation being limited to threats, inciting violence, and “repeated slurs.” 56 Those who create content for online platforms such as Twitter are considered independent contractors and therefore are not offered protection from harassment by the company operating the social media platform they use to generate content. 57

HQ Trivia during COVID-19

The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdowns and stay at home orders were the first time the world as a whole experienced a crisis at the same time since World War II. 58 Not surprisingly, people accessed social media and streamed content more than usual while opportunities for face-to-face interactions were limited. For the first time in most people’s lives, an external event forced a social interaction deficit on many. 59 In the US, Verizon reported a 75% increase in online gaming during the initial stay at home orders. 60

HQ restarted after a six week break in March 2020. During those first months of the game relaunching concurrent with the first wave of the pandemic, the number of HQ players reached levels it had not seen since 2018 and 2019. When it restarted, HQ incorporated something new: a neoliberal model of charity during its daily game. While HQ continued to be an example of the neoliberal idea that leisure time needs to be productive, with the players’ knowledge possibly leading to monetary rewards, now it offered a neoliberal model of charity, with a highlighted charity receiving a donation from HQ based on the number of players in the game. Tying a charitable donation to the number of people participating in the game encouraged players to keep participating in HQ. The host also encouraged users to donate using a link provided by HQ. By doing this, HQ demonstrated two aspects of neoliberal ideas of charity: donations should be market driven, not provided by governments, and charitable distribution should be decentralized.

The first charity supported by HQ during its first week back online was World Central Kitchen (WCK), a non-profit, emergency mobile meal distribution network. 61 While the charities highlighted at the start of the pandemic were in the New York City area, which is both where HQ is based and one of the largest US metropolitan areas first affected by COVID-19, as the pandemic continued, HQ began to spotlight charities in other cities (primarily food banks). These location-based charities are another aspect of the neoliberal perspective on assistance to people, with a decentralization of political decisions and as much responsibility being handled at the local level as possible. 62 HQ switched to a flat $5,000 donation to the highlighted charity in May 2020, rather than tying the amount donated to the number of players staying until the end of the game. Starting in January 2021 the charities featured on HQ included a wider range of organizations, including animal rescue and education focused organizations. The magnification of charities by a business demonstrates how something which was previously considered a duty of the government, the welfare of its citizens, is now part of the economy of business, 63 and part of the neoliberal capitalist economy.

Concurrent with a decreasing number of players, HQ stopped the game-connected charity donations and promotions in late December 2021. The hosts and the social media messages from HQ emphasized that the players as members of the HQ community helped make a difference to others. Realistically the amount given by HQ players and the company was small compared to the overwhelming need, however, HQ did promote information about the need for pandemic related assistance for over one and half years.

HQ’s Liveness Connection to Earlier Forms of Mass Media

The liveness component of HQ reconnects to the ways mass media was first presented. Originally radio and television broadcasts were only available live, and long lines of people waited to see popular movies at times set by the theaters. This liveness created a shared temporality and social reality for the audiences, creating social cohesion. 64 One factor which contributed to television’s success was that it required the audience to watch at a set time, 65 creating expectation of the experience. Audiences were then able to discuss at a later time what they heard or saw with others who also experienced the same event. A major change regarding liveness started in the 1980s, when there was a significant shift from a communal television experience to individualized, time-shifted, and on demand viewing 66 through the use of VCRs. The lack of liveness for mass media continues into the present through video on demand via cable and streaming companies and DVRs. By 2012, more people in the US consumed media through digital devices such as computers and their phones rather than watching it on a TV set. 67 Even social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Reddit were initially designed for asynchronous participation.

But there are now new forms of liveness and shared experiences. Online communication has enabled people to create and share cultural productions more easily. 68 While time-shifted options are available for consuming media, there is a desire for shared spatial and temporal experiences, which include liveness and synchronous happenings. 69 Because HQ can only be played at set times, it requires its players to conform to its structured time, 70 demanding attention at specific times 71 and rewarding players for following its liveness. 72 The liveness of HQ can offer players a collective sense of time. 73

What makes HQ different from live TV shows is that the participatory trivia game is connected with the ability to chat at the same time. 74 Even after a player of HQ is eliminated from the game and no longer able to win money, they are encouraged to continue to watch the game and to participate and react in the chat. 75 The shared experience means players all see the good, the bad, and the quirks of the game at the same time.

Because HQ games are live and produced with a small staff and limited production assets, there can be problems during an HQ broadcast. When that occurs, the hosts need to keep the players entertained so they do not leave the game. 76 While in modern, professional TV shows problems during broadcasts are infrequent, when problems occur on HQ that delay or interrupt the game it helps to reinforce the liveness, sharedness, and sense of being part of a group with the same experiences. 77 These situations are actively discussed in the live chat as they happen, and days afterwards it can also be a topic of conversation between players, the hosts, and the platform on other, asynchronous social media.

Conclusion: The Appeal of Trivia and Liveness in the era of COVID-19

HQ fits into a unique model of being a live trivia game with concurrent interactions as well as having an asynchronous social media component. It depends on its users’ unpaid, immaterial, digital labor and the liveness aspect to create a sense of shared experiences and community, and, at the same time, relies on asynchronous social media to help keep players connected to the game and its hosts. In addition to the liveness, HQ fulfills people’s attraction to new objects and their simultaneous pull towards objects which are familiar. Trivia games are familiar, but HQ places them on a new platform. Players developed affection for the HQ platform and the hosts, while the platform uses this “affective capture” and requires players to conform to its liveness.

Other live streaming services, such as Netflix’s Teleparty and Facebook’s Watch Parties, which allow individuals in different locations to see the same content at the same time, are now part of a renewed emphasis on liveness for services which were previously consumed in a time-shifted model. The several year success of HQ prior to the pandemic, and the continued success of Twitch as it expands its channels, show there is still interest in liveness and shared experiences. While HQ as a live game streaming and chat platform has many positive aspects, it is still firmly within the capitalist and neoliberal models for business and leisure behaviors, including social media. The tying of charity donations to the number of players and the sense that leisure time should have elements of being productive are examples of the pervasiveness of the neoliberal economic model in the US.

The COVID-19 pandemic, with its pressure for people to stay at home and reduce in-person interaction, may increase the appeal of the liveness, not only for games but other media experiences. A sense of affection for the HQ platform and the hosts existed before the COVID-19 pandemic and HQ’s re-emergence after a six week break in March 2020 met a renewed need for liveness among its players. While games with over a million players did not continue as the pandemic persisted, HQ Trivia demonstrates there is a demand for live, social interaction online which is tied to trivia games. Trivia games are a common cultural experience in the US. Liveness, along with a sense of connecting to others over a shared experience, is likely to continue to be important in the era of COVID-19 and social distancing. Even after the pandemic ebbs, many will still strive to find connections to others through live shared experiences online. HQ Trivia ceased operations the last week of January 2023. Humor, a core part of the appeal of HQ, was demonstrated in one of the final games.

Alexander, Jennifer and Kandyce Fernandez. “The Impact of Neoliberalism on Civil Society and Nonprofit Advocacy” Nonprofit Policy Forum, 2020: 1-28. .

Cann, Candi K. Virtual Afterlife: Grieving the Dead in the Twenty-First Century. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2016.

Grandinetti, Justin Joseph. “A Streaming Locality: Mobile Streaming and the Production of Space and Subjectivity, Dissertation in Communications.” PhD diss., North Carolina State University, 2019. Under the direction of Dr. Adriana de Souza e Silva.

Grandinetti, Justin Joseph. “A Question of Time: HQ Trivia and Mobile Streaming Temporality.” M/C Journal 22, no. 6, (2019). .

Harris, Jennifer and Elwood Watson. “Introduction: Oprah Winfrey as Subject and Spectacle.” In The Oprah Phenomenon, edited by Jennifer Harris and Elwood Watson, 1-34. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007.

Higa, Liriel. “Trivia Never Sleeps (Much Past 9).” New York Times, July 1, 2018.

American Medical Association. “Issue brief: Nation’s drug-related overdose and death epidemic continues to worsen.” Accessed November 12. 2021.

Jarzyna, Carol Laurent. “Parasocial Interaction, the COVID-19 Quarantine, and Digital Age Media.” Human Arenas no. 4 (November 2020): 413–429, .

Jenkins, Henry. “Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication, vol. 5, no. 2 (1988): 85-107.

Khairiyah Md Zali, Tara et al. “Attractiveness Analysis of Quiz Games.” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, vol. 10, no. 8 (2019): 205-210.

Kim, Soomin et al. “Game or Live Streaming?: Motivation and Social Experience in Live Mobile Quiz Shows.” CHI PLAY ’19: Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, (Oct. 2019): 87–98. .

King, Daniel I. et al. “Problematic Online Gaming and the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions, vol. 9, no. 2 (2020): 184-186. .

McDonnell, Tom. “HQ Trivia is Setting the Standard for Interactivity.” Broadcast, March 1, 2018.

Paasonen, Susanna, Kylie Jarrett and Ben Light. #NSFW: Sex, Humor, and Risk in Social Media. MIT Press, 2019.

Pereverseff, Rosemary S. and Glen E Bodner. “Comparing Recollection and Nonrecollection Memory States for Recall of General Knowledge: A Nontrivial Pursuit.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, vol. 46, no. 11 (2020): 2207-25.

Riches, Graham. Food Bank Nations: Poverty, Corporate Charity, and the Right to Food. London: Routledge, 2018.

Stings, Sabrina. “Obese Black Women as ‘Social Dead Weight’: Reinventing the ‘Diseased Black Woman’” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society vol. 41, no. 1 (Autumn 2015): 107-130.

Swaminathan, Shakti. “The Show Must Go On: A Study on Celebrity Worship during COVID-19.” Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies, vol. 2, no. 4 (2020): 110-122.

Shaw, Adrienne. “The Internet is Full of Jerks, Because the World is Full of Jerks: What Feminist Theory Teaches Us About the Internet.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 11, no. 3 (2014): 273-277.

Taylor, T.L. Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming. Princeton University Press, 2018.

Thompson, Derek. Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction. Penguin Press, 2017.

Torbet, Georgina. “Facebook Axes Its Confetti Trivia Game in the US and UK: The Company is Leaning into Sports Shows Instead.” Engadget, October 15 2019, .

Twitter. Hateful Conduct Policy 2022,

Warbrick, Isaac, Heather Came, and A. G. Dickson. “The Shame of Fat Shaming in Public Health: Moving Past Racism to Embrace Indigenous Solutions.” Public Health vol. 176 (2019): 128-132.

Wilkie, Dana. “HQ Trivia: The Latest in Potential Workplace Distractions” HRNews. January 16 2018.

World Central Kitchen. “Programs.” (https://wck.org/programs)

Bio:

Terilee Edwards-Hewitt is a PhD student in Cultural Studies at George Mason University, where she is also a graduate lecturer in anthropology. In addition, she teaches anthropology as an adjunct professor at Montgomery College in Rockville, Maryland. She earned her MA in Anthropology and Museum Studies at George Washington University. Her research interests include digital ethnography, gender and sexuality, and popular culture, as well as gender and sexuality in the nineteenth century.

Footnotes

- Justin Joseph Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality: Mobile Streaming and the Production of Space and Subjectivity, Dissertation in Communications.” (PhD diss., North Carolina State University, 2019), 161.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 161.

- Tara Khairiyah Md Zali, Nor Samsiah Sani, Abdul Hadi Abd Rahman, and Mohd Aliff, “Attractiveness Analysis of Quiz Games,” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, vol. 10, no. 8 (2019), 209.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 163.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 165.

- Tom McDonnell, “HQ Trivia is Setting the Standard for Interactivity.” Broadcast, March 1, 2018.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 160.

- Soomin Kim, Gyuho Lee, Seo-young Lee, Sanghyuk Lee and Joonhwan Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?: Motivation and Social Experience in Live Mobile Quiz Shows.” CHI PLAY ’19: Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, (Oct. 2019), 93.

- T.L Taylor, Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming (Princeton University Press, 2018), 40-41.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 92.

- Justin Joseph Grandinetti, “A Question of Time: HQ Trivia and Mobile Streaming Temporality,” M/C Journal 22, no. 6, (2019). .

- Zali, Sani, Rahman, and Aliff, “Attractiveness Analysis of Quiz Games,” 209.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 88.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 93.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 87.

- Dana Wilkie, “HQ Trivia: The Latest in Potential Workplace Distractions,” HRNews. January 16, 2018.

- Georgina Torbet, “Facebook Axes Its Confetti Trivia Game in the US and UK: The Company is Leaning into Sports Shows Instead,” Engadget, October 15 2019. .

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 174.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 92.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 96.

- Kim, Lee, Lee, Lee and Lee, “Game or Live Streaming?,” 95.

- Grandinetti, “A Question of Time.”

- Grandinetti, “A Question of Time.”

- Derek Thompson, Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction (Penguin Press, 2017), 213.

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 214.

- Zali, Sani, Rahman, and Aliff, “Attractiveness Analysis of Quiz Games,” 206.

- Zali, Sani, Rahman, and Aliff, “Attractiveness Analysis of Quiz Games,” 205.

- Rosemary S. Pereverseff and Glen E Bodner, “Comparing Recollection and Nonrecollection Memory States for Recall of General Knowledge: A Nontrivial Pursuit,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, vol. 46, no. 11 (2020), 2207.

- Pereverseff and Bodner, “Comparing Recollection and Nonrecollection Memory States,” 2207.

- Pereverseff and Bodner, “Comparing Recollection and Nonrecollection Memory States,” 2207.

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 7.

- Thompson Hit Makers, 29.

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 44.

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 44-45.

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 56.

- The question which stumps a large majority of players the first time they see it is “What is the main ingredient in Bird’s Nest Soup?” The answer is a Swiftlet bird’s nest. This question has been asked repeatedly since 2017.

- The video of Reggie the Bear, HQ’s mascot, can be viewed at https://twitter.com/hqtrivia/status/1112796684621316103

- Henry Jenkins, “Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication, vol. 5, no. 2 (1988), 474.

- Susanna Paasonen, Kylie Jarrett and Ben Light, #NSFW: Sex, Humor, and Risk in Social Media (MIT Press, 2019), 12.

- Paasonen, Jarrett and Light, #NSFW, 142.

- Jenkins, “Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten,” 472.

- Paasonen, Jarrett and Light, #NSFW, 144.

- Jennifer Harris and Elwood Watson, “Introduction: Oprah Winfrey as Subject and Spectacle,” in The Oprah Phenomenon, edited by Jennifer Harris and Elwood Watson, (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007), 10.

- Harris and Watson, “Oprah Winfrey as Subject and Spectacle,” 10.

- Harris and Watson, “Oprah Winfrey as Subject and Spectacle,” 15.

- Paasonen, Jarrett and Light, #NSFW, 144.

- Isaac Warbrick, Heather Came, and A. G. Dickson, “The Shame of Fat Shaming in Public Health: Moving Past Racism to Embrace Indigenous Solutions,” Public Health vol. 176 (2019), 129.

- Sabrina Stings, “Obese Black Women as ‘Social Dead Weight’: Reinventing the ‘Diseased Black Woman,’” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society vol. 41, no. 1 (Autumn 2015), 108.

- Stings, “Obese Black Women as ‘Social Dead Weight,’” 109.

- Stings, “Obese Black Women as ‘Social Dead Weight,’” 110.

- Paasonen, Jarrett and Light, #NSFW, 151.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 169.

- Candi K. Cann, Virtual Afterlife: Grieving the Dead in the Twenty-First Century (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2016), 10.

- American Medical Association, “Issue brief: Nation’s drug-related overdose and death epidemic continues to worsen,” Accessed November 12. 2021.

- Liriel Higa, “Trivia Never Sleeps (Much Past 9),” New York Times, July 1, 2018, 2.

- Twitter, Hateful Conduct Policy 2022.

- Paasonen, Jarrett and Light, #NSFW, 157.

- Shakti Swaminathan, “The Show Must Go On: A Study on Celebrity Worship during COVID-19,” Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Studies, vol. 2, no. 4 (2020), 110.

- Carol Laurent Jarzyna, “Parasocial Interaction, the COVID-19 Quarantine, and Digital Age Media,” Human Arenas no. 4 (November 2020). .

- Daniel L King, Paul H Delfabbro, Joel Billieux and Marc N Potenza, “Problematic Online Gaming and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Journal of Behavioral Addictions, vol. 9, no. 2 (2020), , 184.

- World Central Kitchen, “Programs,” 2021.

- Graham Riches, Food Bank Nations: Poverty, Corporate Charity, and the Right to Food (London: Routledge, 2018), 33.

- Jennifer Alexander and Kandyce Fernandez, “The Impact of Neoliberalism on Civil Society and Nonprofit Advocacy” Nonprofit Policy Forum, 2020, 4.

- Grandinetti, “A Question of Time.”

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 62.

- Grandinetti, “A Question of Time.”

- Thompson, Hit Makers, 11.

- Adrienne Shaw, “The Internet is Full of Jerks, Because the World is Full of Jerks: What Feminist Theory Teaches Us About the Internet,” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 11, no. 3 (2014), 275.

- Grandinetti, “A Question of Time.”

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 161.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 18.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 182.

- Grandinetti, “A Question of Time.”

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 182.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 164.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 183.

- Grandinetti, “A Streaming Locality,” 184.