Abstract

This article examines the character of Dorothy Zbornak from the television series The Golden Girls. Through the lens of feminist rhetoric and healthcare advocacy, the study analyzes Dorothy's communication patterns in eight episodes addressing various health issues. The research reveals that Dorothy primarily employs logical appeals, makes limited, and often simplistic, emotional appeals; and asserts her credibility through silence or succinct expressions of frustration. These communication strategies are contextualized within Dorothy's identities as an educator, a woman with undiagnosed medical conditions, and a feminist of the 1980s and early 1990s. The article explores the implications of Dorothy's rhetorical approach for women currently navigating the healthcare system, highlighting the complexities of advocacy, empathy, and communication in all spaces. By examining Dorothy's character, the study contributes to discussions on gender, health literacy, and the evolving nature of feminist communication in popular culture and real-world contexts.

Leading up to the time my grandmother was granted custody of me and my brother, I spent weekends with her, watching The Golden Girls on Saturday night and attending church on Sunday morning. That experience solidified the show in my life as a form of comfort—before, during, and after I became like Dorothy Zbornak in multiple ways, such as embodying identities as an educator, a woman with long-undiagnosed medical conditions, and the medical decision-maker, or medical teacher, for her family. It would be easy, then, to romanticize the show and its characters—to appreciate the humor, activism, and comfort without looking more critically at the complexities it presents. Instead, this article examines Dorothy’s interactions with the other “girls” and with medical professionals about issues of health, considering specifically the rhetorical techniques that speak to healthcare literacy and advocacy. It responds to the following questions: What are the rhetorical characteristics of Dorothy’s communication with others regarding health and healthcare? In what ways do these characteristics align (or not) with her identity and literacy as a teacher, as well as with feminism of the 1980s and early 1990s? What are the implications of this for today’s feminists and women patients?

More than thirty years after The Golden Girls’ final episode, there remains a pattern of dismissing women’s illnesses. 1 From physical pain being ignored, 2 to symptoms being incorrectly attributed to mental and emotional health issues, to a lack of accounting for women in scientific research on health, women are undermined in knowing, and communicating about, their bodies. 3 In a form of art imitating life, the ways in which Dorothy, Rose, Blanche, and Sophia experience injustice regarding their physical health, both within and outside of their inner circle, spans dozens of episodes. 4 In these episodes, the characters not only fight against, but also participate in, these problematic dynamics.

The most obvious and explicitly documented example of Dorothy’s feminist literacy practices and subsequent “teaching” is the “revenge script,” from the two-part episode “Sick and Tired.” In this episode, Dorothy experiences a sexist (and ageist) healthcare system, just as the show’s creator, Susan Harris, had. 5 The storyline focuses on Dorothy’s suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. When doctors are bewildered by the inability to diagnose her via a series of medical tests, she is passed from one specialist to another and told that her symptoms are psychosomatic. The commonality of this experience in real life, documented across decades, keeps this episode relatable. 6 As a matter of fact, for years, I had symptoms of fibromyalgia and Meniere’s disease, only to be referred from one specialist to another and told by a primary care physician that I “just need[ed] to get laid.”

Both Dorothy Zbornak and I, however, used our education and experiences of injustice to become strong advocates for ourselves and others. Across many episodes, Dorothy served as an advocate and medical decision-maker for her mother, and as a medical “teacher” for her roommates, most notably in plotlines addressing topics such as sexual and reproductive health, heart health, AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, and drug addiction. Women identifying with Dorothy demonstrates the truth in Schroeder’s assertion that, “Years later, Dorothy’s character continues to instruct.” 7 That being the case, this article bridges the emotional connection I (and many others) have to the show and a more cognitive understanding of how the show functions rhetorically, as seen in feminist communication and pedagogical practices.

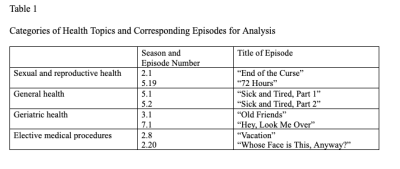

The sample for this inquiry consists of eight episodes spanning Seasons Two, Three, Five, and Seven of the series and addressing issues of sexual and reproductive health (artificial insemination and HIV/AIDS); general health (disease and hospitalization for reasons not commonly associated with age, such as a tumor); geriatric health (dementia and other loss of function commonly related to age); and elective medical procedures (cosmetic surgery). 8 Table 1 shows the final sample for analysis.

These eight episodes feature Dorothy as both a main part of the plot and in more supporting roles to her friends and family. Finally, per the first research question, these episodes were analyzed based on social context and rhetorical appeals of ethos (credibility), pathos (emotions invoked in the audience), and logos (use of logic).

The first question addressed with the data was, “What are the rhetorical characteristics of Dorothy’s communication regarding health and healthcare?” Across the eight episodes in Table 1, I identified fifty-two exchanges of dialogue in which Dorothy addressed one of the categorized health issues (sexual and reproductive health, general health, geriatric health, or elective medical procedures). Of Dorothy’s 52 instances of dialogue, 18 of them primarily address ethos, 10 of them primarily address pathos, and 24 of them primarily address logos. Of course, a single rhetorical appeal often functions in more than one way; for instance, sharing a personal experience with an audience may give the speaker ethos and may aim to invoke a sense of empathy (pathos). Moreover, rhetorical appeals may equally prove difficult to classify in any of the three categories, given the interpretive nature of communication. In these instances, I relied on context to draw conclusions about the purpose of communicative acts.

An analysis, then, of the rhetorical appeals and their patterns reveal the following major findings:

- Dorothy makes few appeals to emotion and mostly appeals to logic.

- Many appeals to emotion that do exist are oversimplified, even falling into what we today might label “toxic positivity.”

- Dorothy’s appeals to ethos are often either silent or expressed succinctly as exasperation.

Addressing the second research question, these rhetorical characteristics both align and do not align with her identity and literacy as a teacher with feminist goals (discussed more thoroughly throughout the text). First, Dorothy’s lack of appeal to emotion (accounting for less than 20% of her rhetorical appeals) is, on one hand expected and, on the other hand, surprising. We might expect that her identity as a high school teacher has either showcased a natural tendency, or an acquired skill, to be empathetic. The awareness and effort required to scaffold student learning while accounting for individual circumstance makes Dorothy a strong teacher (such as when she mentors an immigrant student who writes a prize-winning essay (Season 2, Episode 21) and when she offers one-on-one tutoring to a student football player who needs a passing grade to continue in the sport (Season 6, Episode 6). But the constant demand of being attuned to the needs of others—amidst a mix of problematic social variables, such as gender and age discrimination, also makes this demand exhausting and unsustainable. For instance, the burnout and turnover rate of K-12 teachers, from the 1980s

9

to the present,

10

remains well documented. Five years prior to the show’s premiere, “The First National Conference on Teacher Stress and Burnout” took place in New York City.

11

The 1980s saw the introduction of national standards for student performance, which placed added pressure on teachers to prepare students for tests and reduced teacher autonomy;

12

this was accompanied by teacher education reforms that also called into question the credibility and professional status of teachers.

13

The increased anxiety about the quality of American education, accompanied by lack of confidence in teachers’ ability, low salaries in comparison to other occupations, frustrations over lack of advancement opportunities (such as administrative positions) that include or seem to value teaching, increased demands on time, lack of materials and resources, large class sizes, lack of support from school districts, and teachers’ subsequent feelings of guilt and/or inadequacy all contributed to teacher burnout in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s.

11

Perhaps Dorothy’s years as an educator left her with decreased energy and patience to process and address the emotions of others. “Compassion fatigue,” then, may play a role in her communication dynamics. Primarily associated with caregiving professions such as those in medicine, psychological services, and the clergy, compassion fatigue refers to the decreased ability to feel compassion or empathy for one’s patients or clients. 14 This decreased ability stems from the mental exhaustion that comes from caring about, not just for, people. This sense of carrying the burdens of others has also been used interchangeably with the terms “vicarious traumatization,” “secondary trauma syndrome,” “secondary trauma stress (STS),” counter-transference,” “SDS disorder,” “burnout,” and “helper stress.” 15

Moreover, perhaps Dorothy’s embodied masculine qualities, such as deep voice, tall height, “stern manner,” and “masculine reasoning” 16 influence her lack of trying to engage others’ emotions, as emotional engagement would align with notions of femininity. 17 Either way, the gendered expectation for women to nurture by helping to manage—or even take responsibility for—the emotions of others, 18 and the ways in which Dorothy consciously or subconsciously defies this expectation, may further set Dorothy’s identity apart from the rest of “the girls.”

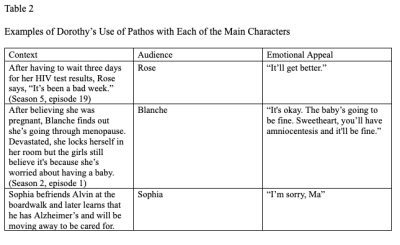

Aside from the relative lack of emotional appeals overall, we see a lack of sophistication in the emotional appeals she does use. Given Dorothy’s intellect and profession as a teacher, this also comes as somewhat of a surprise; we might expect her to demonstrate a broader repertoire of communication tactics. Table 2 provides examples of Dorothy’s emotional appeals, detailing a response to the research question, “What are the rhetorical characteristics of Dorothy’s communication regarding health and healthcare?” in terms of pathos.

The first example, Dorothy’s response to Rose, is intriguing because it preceded the 2010 “It Gets Better Project” by 30 years. The “It Gets Better Project” uses personal stories of LGBT+ individuals to support people in overcoming challenges and trauma associated with being minoritized. 19 The message has merit. I frequently stress to my students the sentiment that “This too shall pass.” But I also make clear that while whatever they face may be temporary and, indeed, will get better, circumstances will also get equally bad or worse at some point in their lifetimes. Life experiences are not linear, and an oversimplification of that fact may leave some students unprepared to be resilient. While “It gets better” can offer an element of hope, without deeper engagement, it can appear as a brush-off, a cliché, a response that fulfills a social expectation more than it serves any other purpose. Responses such as these can encourage one to shut down their feelings in favor of just “skipping to the hope.” 20 The reality is that acknowledging and processing negative feelings while recognizing their purpose and limitation in our lives allows one to adopt a positive mindset that may increase functionality. Psychology Today further notes:

Positivity is also particularly unhelpful in certain situations. Research suggests that looking for silver linings is beneficial in uncontrollable contexts, such as being laid off, but harmful in situations that [people] can control. Using positivity when one’s identity is threatened, such as in the case of experiencing racial oppression, also leads to lower well- being. Encouraging someone to use an emotional regulation strategy that they aren't skilled at can also lower well-being. 21

In other words, engaging with emotion is a rhetorical and a psychological skill that involves nuanced awareness and subsequent choices in behavior. But this is not encompassed in Dorothy’s communication with others about their health (or her own).

Like positive thinking, Dorothy’s responses to Blanche and Sophia have similar affordances and limitations. Dorothy might offer a different, welcome perspective on the storylines. She grounds her emotional appeal to Blanche in logic, noting the role of science and hinting at its “objective” evidence in providing reassurance. Moreover, her simple response to Sophia, “I’m sorry,” can create better empathy than a more elaborate response, especially if saying more will isolate the listener by comparing experiences or engaging in toxic positivity. As we see in Dorothy’s ensuing monologue with Dr. Budd, she recognizes the value in this simplicity. So, we cannot characterize the nature of Dorothy’s responses as “wrong” But the lack of sophistication we might expect from her is illustrated in the abruptness of the exchanges, their lack of invoking additional conversation with the listener, therefore shutting down a more intimate exchange.

Dorothy’s most verbose appeal to empathy comes in her monologue to Dr. Budd, whom she encounters at a restaurant after finally receiving her diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. She states:

Dr. Budd, I came to you sick—sick and scared. And you dismissed me. You didn’t have the answer and instead of saying ‘I’m sorry, I don’t know what’s wrong with you,’ you made me feel crazy, like I had made it all up. You dismissed me. You made me feel like a child, a fool, a neurotic who was wasting your precious time. Is that—is that your caring profession? Is that healing? No one deserves that kind of treatment, Dr. Budd. No one . . . I don’t know where you doctors lose your humanity, but you lose it. If all of you, at the beginning of your careers, could get very sick and very scared for a while, you’d probably learn more from that than anything else. You’d better start listening to your patients. They need to be heard. They need caring. They need compassion. They need attending to. Someday, Dr. Budd, you’re going to be on the other side of the table. And as angry as I am, and as angry as I always will be, I still wish you a better doctor than you were to me. (Season 5, Episode 2)

As Dorothy appeals to Dr. Budd’s empathy and compassion, she makes herself vulnerable, naming her emotions: scared, foolish, dismissed. She instructs by pointing out the errors in Dr. Budd’s performance of his duties and makes a suggestion for correction—to admit his lack of knowledge and validate the patient. She advocates for patients’ needs and implicitly provides commentary on doctors’ training, claiming that she does not know “where . . . doctors lose humanity” but that it seems to be “at the beginning of [their] careers.” (In her appeal to logos here, she also explicitly names the role her age and gender may have played in his dismissiveness of her concerns). While Dorothy does not demonstrate listening, cutting off Dr. Budd every time he tries to speak, she does demonstrate a series of rhetorical skills for Dr. Budd to emulate: making appeals to pathos and logos, contextualizing her arguments, speaking with precision, and offering practical suggestions for modifying his approach.

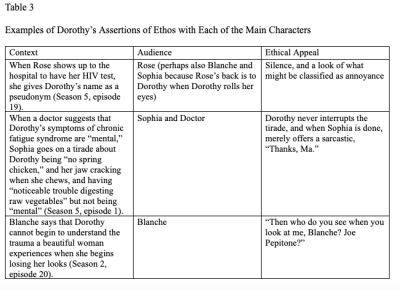

The third pattern in Dorothy’s communication pertains to ethos, whereby she often asserts credibility silently or succinctly through frustration, instead of explicitly and through her previously mentioned “masculine reasoning.” Table 3 provides examples of her assertions of credibility to other characters, detailing a response to the research question, “What are the rhetorical characteristics of Dorothy’s communication regarding health and healthcare?” in terms of ethos.

The implied lack of need to defend her ethos may stem from her characterization as more masculine than the other main characters. Simply put, many men do not feel the need to assert credibility; they have it and it is often unquestioned. 22 This may be particularly true in professional spaces like those in healthcare. Therefore, as a character constructed as more masculine than her counterparts, Dorothy may feel particularly annoyed when her ethos is questioned regarding matters of health; it may be less common and more offensive than such an experience would be for the other characters, who are perhaps more used to having their ethos questioned as a result of their female or feminine identity. 23 Perhaps, though, her responses are a result of her teacherly identity, whereby her education and her profession make her feel that she has credibility as an authority figure, and she does not need to defend it. This may also align with the feminist move to seek positions of authority and assert power (whether implicitly or explicitly). Or, her identities as a woman and a teacher have intersected in such a way that she no longer has the energy or will to defend her credibility; she is self-confident and that is enough. Like many women (regardless of number or degree of stereotypical male and female, manly or womanly, features and characteristics), however, self-confidence fails to shield her from frustration when her ethos is questioned, not just by men like Dr. Budd but by fellow women, even ones as close to her as her mother and friends.

As we understand the relevance of these communicative acts and their accompanying feelings and notions of identity, we understand a response to the final question: “What are the implications of this for today’s feminists and women patients?”—for all women who came after Dorothy and the rest of the Golden Girls. Dorothy embodies the second- and third- wave feminist principles of her time, which encouraged working outside of the home, asserting individuality, seeking positions of power, and continuing to address unjust social structures. 24 For example, she has a college degree and a career outside the home, having left her cheating husband; she advocates for herself and others on a variety of issues including physical well-being; and she employs rhetorical techniques that blend traditionally isolated “male” and “female” ways of communicating. In these ways, her compassion, assertiveness, and biting wit perhaps provide a model for current feminists and women navigating the complex healthcare system.

But Dorothy doesn’t always “get it right.” Neither do any of us—patients, doctors, caregivers, advocates, teachers, students. We are grounded in our subject positions and limited by social and physical context. If we care about justice, we make an honest and continuous attempt to educate ourselves and not offend or hurt others. But all acts of communication are subjective. The reality is that we do sometimes unintentionally hurt and/or offend others with our words or actions. And we get hurt by the words and actions of others. One factor that seems to impact the outcome of how relationships continue or end (and this is not new) is a willingness to practice grace—at least initially and in many circumstances—in drawing inaccurate and unfair conclusions about egregious motives. This, of course, is not to suggest that explicitly egregious acts do not occur and should not be denounced, but rather to say that we should proceed with empathy when we can.

I have found both professional spaces and healthcare spaces to present complexities regarding my identity, my vulnerabilities, my authority, and the ways others perceive these. In each space, I have exercised agency, such as designing courses and presenting a medical journal article to a physician treating one of my conditions (who asked to keep the article at the end of my appointment). In other words, like Dorothy, I have tried to use my agency as a means of collaborating, of being a thought partner. But as a teacher and as a patient, I have often felt a lack of agency to change unjust systems and a lack of reception to my well-intentioned behaviors. I have also, though, unintentionally offended department chairs and doctors alike. I have been misunderstood. And I have sometimes been quick to judge the intentions and the methods of those who, to some degree, have power over me (in the sense that they make decisions about my physical, financial, or even mental well-being). I am learning when—and how—to advocate for myself and others, whether quietly or loudly or through action or inaction. I am, therefore, calling for compassionate advocacy on all fronts and from all stakeholders. While imperfect, Dorothy embodied her teacherly identity by connecting with others in effective ways and learning continually. And we can appreciate the positive ways the Golden Girls sitcom impacts our lives while realizing and acknowledging its shortcomings.

Footnotes

See, for example, "Women and Pain: Disparities in Experience and Treatment." Harvard Health Blog, October 9, 2017; Afflicted. Directed by Peter Logreco and Dan Partland. Doc Shop Productions, 2018; Dusenbery, Maya. Doing Harm: The Truth about Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick. New York: HarperOne, 2018; Hossain, Anushay. The Pain Gap: How Sexism and Racism in Healthcare Kill Women. New York: Simon Element, 2021; “Why Are Women's Health Concerns Dismissed So Often?" NPR.org, January 4, 2023; Burton, Susan. "For Many Women, Tolerating Pain Is the Only Choice They Have." The New York Times, July 30, 2023.

Burton, “For Many Women”.

“Why Are Women’s Health Concerns Dismissed So Often?”

Royal, Sarah, and Lauren Kelly. "A Complete List of the Dark & Dramatic Themes in the Golden Girls." Enough Wicker, December 22, 2020. https://www.enoughwicker.com/post/a-complete-list-of-the-dark-dramatic-themes-in-the-golden-girls.

Shipley, Diane, Jaclyn Friedman, and Aubrey Hirsch. "30 Years Ago, 'The Golden Girls' Treated Sick Women like We Matter." Bitch Media, August 7, 2019. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/the-golden-girls-chronic-fatigue.

Shipley and Friedman, "30 Years Ago.”

Schroeder, Stephanie. "Chapter Twenty-Eight: 'The Golden Girls': Dorothy Zbornak and Lessons about Social Class." Counterpoints 486 (2017): 195. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45177637.

To select episodes for analysis, I consulted Sarah Royal and Lauren Kelly’s’s blog post, “A Complete List of the Dark & Dramatic Themes in The Golden Girls” and determined 17 of their 122 themes to be potentially relevant to my work: addiction, aging, artificial insemination, dementia, disability, disease (hospitalization), euthanasia, HIV/AIDS, medical malpractice, menstruation, menopause, misdiagnosis, organ transplant, plastic surgery, sexual health, teen pregnancy, and transgender issues. I eliminated “medical malpractice” because the episodes exploring that theme were accounted for elsewhere in my categorization. I eliminated “euthanasia” and “transgender issues” because only one episode each covered these topics (and with the episode addressing transgender issues glossing over the topic rather than making it a “theme”), making it difficult to form a “category.” I eliminated “disability” because of arguments about ability vs. health. Finally, I eliminated “addiction” because parsing out “mental health” and “physical health” in issues such as these would work against the goal of creating more manageable, more clearly defined categories for analysis.

Cunningham, William G. "Teacher Burnout—Solutions for the 1980s: A Review of the Literature." The Urban Review 15, no. 1 (March 1983): 37-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01112341.

Smith, Morgan. "'It Killed My Spirit': How 3 Teachers Are Navigating the Burnout Crisis in Education." CNBC, November 22, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/11/22/teachers-are-in-the-midst-of-a-burnout-crisis-it-became-intolerable.html.

Cunningham, “Teacher Burnout.”

Peterson, Wendy A. "From 1871-2021: A Short History of Education in the United States." Buffalo State University, December 8, 2021. https://suny.buffalostate.edu/news/1871-2021-short-history-education-united-states.

Ravitch, Diane. "Education in the 1980s: A Concern for 'Quality'." Education Week, January 10, 1990. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/opinion-education-in-the-1980s-a-concern-for-quality/1990/01.

Coetzee, Siedine K., and Heather K.S. Laschinger. "Toward a Comprehensive, Theoretical Model of Compassion Fatigue: An Integrative Literature Review." Nursing & Health Sciences 20 (2018): 4-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12387.

Coetzee and Laschinger. “Toward a Comprehensive, Theoretical Model,” 4.

Grant, Jo Anna, and Heather L. Hundley. "Myths of Sex, Love, and Romance of Older Women in Golden Girls." In Critical Thinking about Sex, Love, and Romance in the Mass Media, edited by Mary-Lou Galician and Debra L. Merskin, 108. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2007.

Weiss, Avrum. "Why Men Get Uncomfortable When Women Get Emotional." Psychology Today, January 1, 2022. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/fear-intimacy/202201/why-men-get-uncomfortable-when-women-get-emotional.

Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, and Renee Stepler. "Americans See Different Expectations for Men and Women." Pew Research Center, August 6, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/12/05/americans-see-different-expectations-for-men-and-women/.

"About." It Gets Better Project, September 29, 2022. https://itgetsbetter.org/about/.

"Toxic Positivity." Psychology Today. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/toxic-positivity.

"Toxic Positivity."

"Report Reveals Nearly 90 Percent of All People Have 'a Deeply Ingrained Bias against Women'." UN News. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1058731.

Elsesser, Kim. "Labeling Women as 'Emotional' Undermines Their Credibility, New Study Shows." Forbes, November 2, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2022/11/01/labeling-women-as-emotional-impacts-the-legitimacy-of-their-arguments-according-to-new-study/?sh=5acd85bb5b90.

Pruitt, Sarah. "What are the Four Waves of Feminism." History, October 4, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/feminism-four-waves.

References

Bibliography

"About." It Gets Better Project, September 29, 2022. https://itgetsbetter.org/about/.

Afflicted. Directed by Peter Logreco and Dan Partland. Doc Shop Productions, 2018.

Burton, Susan. "For Many Women, Tolerating Pain Is the Only Choice They Have." The New York Times, July 30, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/30/briefing/the-retrievals-serial.html

Coetzee, Siedine K., and Heather K.S. Laschinger. "Toward a Comprehensive, Theoretical Model of Compassion Fatigue: An Integrative Literature Review." Nursing & Health Sciences 20 (2018): 4-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12387.

Cunningham, William G. "Teacher Burnout--Solutions for the 1980s: A Review of the Literature." The Urban Review 15, no. 1 (March 1983): 37-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01112341.

Dusenbery, Maya. Doing Harm: The Truth about Bad Medicine and Lazy Science Leave Women Dismissed, Misdiagnosed, and Sick. New York: HarperOne, 2018.

Elsesser, Kim. "Labeling Women as 'Emotional' Undermines Their Credibility, New Study Shows." Forbes, November 2, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2022/11/01/labeling-women-as-emotional-impacts-the-legitimacy-of-their-arguments-according-to-new-study/?sh=5acd85bb5b90.

Grant, Jo Anna, and Heather L. Hundley. "Myths of Sex, Love, and Romance of Older Women in Golden Girls." In Critical Thinking about Sex, Love, and Romance in the Mass Media, edited by Mary-Lou Galician and Debra L. Merskin, 108. New York: Taylor & Francis, 2007.

Hossain, Anushay. The Pain Gap: How Sexism and Racism in Healthcare Kill Women. New York: Simon Element, 2021.

Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, and Renee Stepler. "Americans See Different Expectations for Men and Women." Pew Research Center, August 6, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/12/05/americans-see-different-expectations-for-men-and-women/.

Peterson, Wendy A. "From 1871-2021: A Short History of Education in the United States." Buffalo State University, December 8, 2021. https://suny.buffalostate.edu/news/1871-2021-short-history-education-united-states.

Pruitt, Sarah. "What are the Four Waves of Feminism." History, October 4, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/feminism-four-waves.

Ravitch, Diane. "Education in the 1980s: A Concern for 'Quality'." Education Week, January 10, 1990. https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/opinion-education-in-the-1980s-a-concern-for-quality/1990/01.

"Report Reveals Nearly 90 Percent of All People Have 'a Deeply Ingrained Bias against Women'." UN News. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1058731.

Royal, Sarah, and Lauren Kelly. "A Complete List of the Dark & Dramatic Themes in the Golden Girls." Enough Wicker, December 22, 2020. https://www.enoughwicker.com/post/a-complete-list-of-the-dark-dramatic-themes-in-the-golden-girls.

Schroeder, Stephanie. "Chapter Twenty-Eight: 'The Golden Girls': Dorothy Zbornak and Lessons about Social Class." Counterpoints 486 (2017): 195. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45177637.

Shipley, Diane, Jaclyn Friedman, and Aubrey Hirsch. "30 Years Ago, 'The Golden Girls' Treated Sick Women like We Matter." Bitch Media, August 7, 2019. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/the-golden-girls-chronic-fatigue.

Smith, Morgan. "'It Killed My Spirit': How 3 Teachers Are Navigating the Burnout Crisis in Education." CNBC, November 22, 2022. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/11/22/teachers-are-in-the-midst-of-a-burnout-crisis-it-became-intolerable.html.

"Toxic Positivity." Psychology Today. Accessed December 17, 2023. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/toxic-positivity.

Weiss, Avrum. "Why Men Get Uncomfortable When Women Get Emotional." Psychology Today, January 1, 2022. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/fear-intimacy/202201/why-men-get-uncomfortable-when-women-get-emotional.

"Women and Pain: Disparities in Experience and Treatment." Harvard Health Blog, October 9, 2017. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/women-and-pain-disparities-in-experience-and-treatment-2017100912562.

“Why Are Women's Health Concerns Dismissed So Often?" NPR.org, January 4, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/01/04/1146931012/why-are-womens-health-concerns-dismissed-so-often