Abstract

James Nulick’s Boycrush is a picture book that has been given a Young Adult (YA) designation. The fourteen-year-old protagonist Nico is depicted in a sparse and episodic narrative about his identity, his performance of various masculinities, and his inchoate sexuality. Pictures of inanimate objects stand as analogs for the relationships of peers and family Nico does not have. This close reading uses Lee Edelman’s seminal work No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive as a lens to analyze Boycrush. Edelman’s work asserts the concept of “the Child” and Queerness as socially oppositional forces. As Nico discusses his crush on his classmate Jaime and his sense of normalcy, he embodies the tension between these forces.

Conservative political groups like Moms for Liberty are currently engaged in a campaign to ban (and in some cases burn) books for young people which have LGBTQIA+ themes and characters. These activists are operating within a paradigm Lee Edelman articulates in No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive which sets up his concept of “the Child” and Queerness as socially oppositional forces. Edelman’s theory critiques our societal emphasis on reproductive futurism, which idealizes and prioritizes the figure of “the Child” as the symbol of future hope and continuity. Edelman argues that this focus marginalizes queer identities that do not align with heteronormative reproductive goals. James Nulick’s new book, Boycrush, a picture book with a Young Adult (YA) designation, challenges the idea that these forces, “the Child” and Queerness, are oppositional, while simultaneously subverting them through a sparse and episodic narrative about fourteen-year-old boy named Nico.

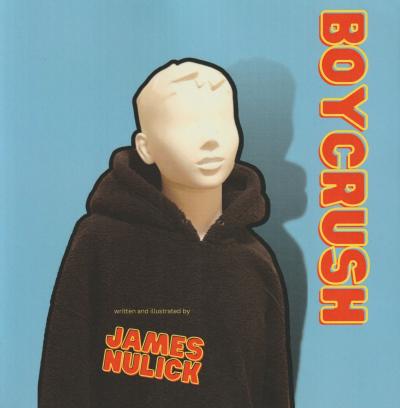

Throughout Boycrush, Nico is on the precipice of something, though we are not quite sure what. The narrative begins with two juxtaposed images: one of him in a black hoodie; the other of him in a pink hoodie. Similar images are also found on the front and rear cover and set up a tension concerning his identity and his performance of various masculinities as he confronts his inchoate sexuality. Pictures of inanimate objects stand as analogs for the relationships of peers and family he does not have. Jaime, the boy Nico has a crush on who is not depicted, seems to be only an object for Nico’s unreciprocated yearning. What is beyond the precipice is unclear; however, it seems as if Nico is shedding the social value he has as a child as he winds towards Queerness.

This close reading uses Edelman’s construction of the child and its complicated relation to queerness to examine potential readings of Boycrush.

The Child

In his book, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Lee Edelman argues that “the child” is the focus of heteronormativity and reproductive futurism. The child is also tasked with the recovery of the past by the perpetual postponement of the future. 1 The urge to protect this imaginary future child relies on a nostalgia for a universal innocent childhood that, when applied to actual individual children, most likely never existed—not for historic children, children of the present, or even the childhoods of the believers of this doctrine itself.

The protection of the child is absorbed into the US political matrix transcending the political spectrum and making its way into common US discourse about the future. The child becomes the fixed point of the political imagination on which the future might be projected. Although the child is idealized and imagined to eventually be permitted the full range of privileges and rights afforded to a fully franchised American, the child remains an imagined being unfettered by the complications of actual existence. The child as imperative and abstraction becomes a universalizing or totalizing figure for whom we, adults in the US, forfeit our desires, rights, and privileges to serve the innocent ideal.

Protection of the imagined child is achieved through limiting the rights of real humans. 2 In Bad Education, Edelman further asserts the child is also conceived of as a possession the parent may prevent from exercising authority and experiencing pleasure. 3 This refinement of the principle of the child reveals that heteronormative power structures must even exert power on their ideal subject, denying its full potential through devotion to the continuity of reproductive futurism.

The child becomes a tool in which not only heteronormativity but whiteness is falsely universalized. José Esteban Muñoz acknowledges that Edelman is aware of the distinction between the ideal child and actual children. 4 Yet Muñoz also observes that Edelman, in deracinating examples and not acknowledging or considering their racial and cultural contexts, is complicit in a reading of the child that obscures the potential of BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ children.

Queerness

Muñoz’s interpretation would suggest that, for Edelman, the queer child would seem to be oxymoronic, if not entirely inconceivable. Edelman’s understanding of queerness is in opposition to the child and its imperative towards reproductive futurism. In particular, “queerness . . . is understood as bringing children and childhood to an end.” 5 Alternatively, although the child is crucial in understanding reproductive futurism and especially in imagining a social regime that exists in continuity after and without current participants in this regime, queerness represents a rupture in its episodic and defining experience of jouissance or pleasure, be it physical or intellectual. This understanding of queerness aligns Edelman with Leo Bersani in the positioning of queerness as individualistic or non-communal, 6 even to the point of being considered “antisocial.” 7

Despite drawing on Edelman to frame our analysis of Boycrush, we opt for an understanding of queerness that centers on non-normative modes and patterns of life that resist hegemonic social conventions. Our understanding is informed by Halberstam’s explanation of Queer Studies as “one method for imagining, not some fantasy of an elsewhere, but existing alternatives to hegemonic systems.” 8

Boycrush

James Nulick’s Boycrush (2023) is a YA photo-picture book. In each photo-illustration, the protagonist is represented by a white mannequin, faceless and boyish in form. The photo illustrations are simple and surface. The setting purports to be the apartment he shares with his mother, yet it is curiously devoid of ornamentation or decorative objects. It looks like a hotel.

The eighth-grade protagonist, Nico, is not comfortable with his body since he is shorter than the other kids. He feels like he will have more friends once he is taller. Nico struggles with his affection for another boy in his class, Jaime. He resists sitting in Jaime’s seat and wishes he could be the outline of the comb in Jaime’s back pocket. Nico knows these feelings are not normal. He tries not to think about Jaime but does so anyway in the privacy of his shower. He wishes his feelings would go away.

His social life is nonexistent. He likes riding his bike. He doesn’t feel like he can join the other kids who either ignore him or call him names. He was called gay for the first time at twelve and this has made him cautious of others. He knows that “boys are not supposed to think about other boys the way [he] thinks about Jaime.” 9 Similarly he likes shooting hoops but doesn’t feel like team sports are for him, especially because he doesn’t like to shower at school.

Nico doesn’t get much affection at home. His father left when he was 10. His mom is frequently gone, presumably working at the department store. She tells him he is handsome because he looks like his father. This observation hurts him but he doesn’t tell her this. He tries to take over some adult responsibilities by cooking, but it is mostly frozen foods, like pizza. She also tells him he will make a good husband, to which he responds by asking her “What if I don’t want a girlfriend.” 10

Clothes provide him an emotional outlet. He enjoys drawing potential outfits and dressing up while he is at home alone. He is proud of his drawing ability. He makes use of his mother’s employee discount for his wardrobe. He is fascinated by how clothes both hide and reveal who he is. After his mother buys him a fuzzy pink hoodie, she tells him, “Things are going to be difficult for you,” without explanation. 11

Nico's mother may be absent, but she does care about his safety. She gives him a cross for protection which he wears under his clothes. The desire for protection is latent throughout the story, perhaps uncomfortably symbolized by the handgun which she has hidden in her closet. Nico sometimes takes this gun just to play with, but he always returns it before she notices.

Nico is looking for some way to escape. He imagines walls disappearing and dreams of floating away and never coming back. He wonders if anyone would miss him if he were gone. He is not even sure if his mom would. Nulick returns to the question, “Can you love an inanimate object?” Each time he reassures us: “I think you can.” The question is asked and answered six times. Each time it is given an entire page to itself. Yet we are never told what the inanimate object to which this love is directed, nor are we sure of whether the speaker is an omniscient narrator, the author, or Nico.

Backing Away from the Future

Nico’s mother may have left latent traces of reproductive futurity in her interactions with her son. Provisioning him with a cross for protection or indicating that he physically resembles his father and is therefore attractive suggests his reproductive potential similarly to her speculation that he could be successful in a heteronormative relationship as a “good husband.” Yet she also indicates that she anticipates Nico is not destined for such a future since she knows, “things are going to be difficult for him,” which indirectly recognizes his queerness. The reader recognizes this, as do his peers who have already labeled him as gay. At the very least, this label serves to ostracize Nico, since he knows that people label him as gay even if he does not yet have a label for himself.

Regardless of sexual orientation or identifications, Nico also seems to be realizing through his fantasies his future will also be unlike that of his peers. Perhaps like Muñoz’s understanding of queerness as a characteristic always in the process of becoming, his thoughts of disappearance suggest Nico and his identity are always in the process of coming and becoming. On the final page Nico wonders rhetorically, “I wonder if my mom would miss me. I wonder if anyone would miss me.” 12 His thoughts of disappearance and potentially not being missed are ambiguous. These thoughts may reflect a potential Queer future, but they may also indicate a trajectory that leads to self-obliteration (whether real or metaphoric). Death is not invoked directly, but the ambiguity of Nico’s fantasies may allude to it. The detached specter of death may also be understood through Edelman’s association of Queerness with the death drive. A component of this association is the access of the Queer to jouissance (in contrast to the reproductive futurity of the straights).

If Nico does experience joy, it does not seem to be with his crush, his peers, or his mother. It is perhaps through inanimate objects that he can experience joy, which is why the book returns to the refrain “Can you love an inanimate object?” Adding to the general ambiguity in the book, there is uncertainty of who asks this question since it is set aside from the normal flow and typography of the narrative. The question seems too philosophical for our fourteen-year-old narrator. It also seems to question and threaten the pleasure and derivative meaning that Nico takes from a variety of inanimate objects (Jaime’s comb, the pink hoodie, the bike, his mother’s gun). If the inquirer’s belief that you can love an inanimate object is untrue, then Nico is deprived of any meaningful connection.

Nico’s relationship with objects also becomes a way in which he starts the process for self-discovery and self-definition. The pink hoodie provides Nico a chance to experiment with non-normative masculinity. The tension of Nico’s gender performance/sexual identity is introduced on the first page of the narrative in two images. In one he wears a black hoodie in the other a pink. These two images appear on the front and back cover respectively. Yet the hoodie is also a possession that allows his mother to postulate the difficulty he may face either because he may be gender nonconforming or perhaps Queer. Taken alone the hoodie might seem insignificant, but given that he acknowledges that classmates already call him gay, this small transgression demonstrates a willingness to challenge gender expectations.

However, Nico is also experimenting with more traditional forms of masculinities. The most explicit form of this experimentation with normative presentation is when Nico plays with the gun his mother has hidden in her closet. Although he returns it to the hiding place, when he has it out he will place it in the waistband of his pants in emulation of gangsters in old movies. Movie gangsters serve as arch masculine and heterosexual icons which may present Nico with the opportunity to rehearse these characteristics which others do not associate with him. This rehearsal recalls Judith Butler’s contention that “gender is an act which has been rehearsed much as a script survives the particular actors who make use of it, but which requires individual actors in order to be actualized and reproduces as reality once again.” 13 The rehearsal of masculinity may be cause for attention as Halberstam notes white male masculinity is marked by a lack of care for the self and others. 14

The gun and its connotation of potential violence may be a startling addition to objects that Nico reflects on. The gun may allow Nico to rehearse the hetero-masculinity his peers do not associate with him. But his emotional frankness does not include any indication of a violence turned to those who ostracize or ignore him. However, the book closes with Nico discussing dreams and fantasies of disappearing or nonexistence, which may be a sublimated suicidal impulse. The ambiguous nature of the narrative does not clarify the nature of Nico’s nihilism. But there is a potential end for Nico emerging from his experience. Like Halberstam and Muñoz’s reading of Edelman and Bersani’s Queerness, Nico displays noncommunal behaviors and attitudes (like his avoidance of peers because of their verbal bullying and policing of his identity).

Nico’s exploration in objects and potentialities which might distinguish him from his peers highlight this difference, but may also mark the end of his childhood, which Edelman indicates requires the limit of potential to the reproductive future. Nico indicates that he may never be a husband and that the comparisons to his father hurt him. This suggests that he is considering non-reproductivity in ways that are deeper and more complex than mere attraction to another boy. The awareness of his difference from his peers and the expectations of his sole parent suggest that Nico may be leaving the concrete status of a child and entering into the even more ambiguous and unformed state of Queerness. The future, if any, available to Nico will not be the one he has been socialized to, but he is still exploring the roles available to him through that socialization, perhaps intuiting that they all will restrict him until he finds a way to discover himself and his own way forward—perhaps, like Muñoz, to an understanding of a Queerness that is full of new potential and always imminent instead of a Queerness that merely forecloses potential to the ephemerality of joy.

Conclusion

Tension is inherent even in labeling the novel YA, which seems intentionally antagonistic to the child as the narrative intentionally queers the use of the label. A juxtaposition arises again: Boycrush appears to be an early reader, few pages, limited vocabulary, and simple sentences. Formally, the book appears not mature enough for the YA designation. Yet the content of the narrative reads too mature for a YA audience and that understanding the complexity of the story would be available only to adult readers. This makes the book queer in the same way Nico is queer and any object may be queer: there is no straight reading offered. Nico and the reader are offered a multiplicity of potential outcomes. Only one thing is clear, the perpetual postponement of the future is coming to an end for Nico.

Footnotes

Lee Edelman, Bad Education: Why Queer Theory Teaches us Nothing, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022).

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004).

Edelman, Bad Education, 18.

José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NewYork University Press, 2009).

Edelman, No Future, 19.

See, for example, Jack Halberstam, Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (Durham, NC: Duke University

Press. 2020); José Esteban Muñoz, The Sense of Brown (Durham, NC: Duke University

Press. 2020).

Robert Caserio, “The Antisocial Thesis in Queer Theory,” PMLA 121, no. 3 (2006): 819, https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2006.121.3.819.

Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham, Duke University Press, 2011), 89.

James Nulick, Boycrush (Anxiety Press, 2023), 13.

Nulick, Boycrush, 42.

Nulick, Boycrush, 24.

Nulick, Boycrush, 46.

Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology

and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal, 40, no. 4 (1988), 526, https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893.

Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham, Duke University Press, 1998).

References

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4: 519–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893.

Caserio, Robert. 2006. “The Antisocial Thesis in Queer Theory.” PMLA 121, no. 3: 819-821. https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2006.121.3.819.

Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004.

Edelman, Lee. Bad Education: Why Queer Theory Teaches Us Nothing. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022.

Halberstam, Jack. Female Masculinity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Halberstam, Jack. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2020.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: NewYork University Press, 2009.

Muñoz, José Esteban. The Sense of Brown. Duke University Press, 2020.

Nulick, James. Boycrush. Anxiety Press, 2023.