Abstract

The pleasure of Buzzfeed personality quizzes comes not from the psychological insights they provide, but the way in which they encourage us to cast ourselves into new roles in both fictional and real worlds. The unconscious mental operation cognitive scientists Gilles Faucconier and Mark Turner refer to as conceptual blending theory can help us to understand that these quizzes are popular and fun, not because of what they tell us about ourselves, but because when we take them, we enact a brief fantasy through which we imagine different iterations of the self.

“Everyone Is 50% Disney And 50% Harry Potter Character — Who Are You?” 1 “Tell Us What You Look For In A Partner And We'll Tell You Which ‘Riverdale’ Guy You'd End Up With,” 2 “Which ‘Game Of Thrones’ House Were You Destined To Be In?” 3 No matter what you are a fan of, chances are that Buzzfeed has at least one personality quiz you can take to “reveal” which character you are like, who you would date, how you fit into that world. While these quizzes can be taken by non-fans of their subjects, they are more meaningful for fans who have a deep understanding and affective attachment to their subject. Or rather, because of fans’ encyclopedic knowledge of and emotional connection to their fan objects, they generate more meaning from results because they understand the associations and entailment that comes with different Disney and Harry Potter characters, guys from Riverdale, and the Game of Thrones houses. The ability to play with our identities, to cast ourselves as these characters, into these roles, and as a part of these worlds, I argue, is where our pleasure in taking personality quizzes comes from. If these quizzes help us to better understand who we are, it is not because they “reveal” anything, but because through casting and imagining ourselves in these different universes and as different characters, we generate new versions of ourselves, which we can integrate into how we conceptualize ourselves.

A number of scholars and cultural critics have argued that we are motivated to take these kinds of quizzes because we believe that they can provide us with insights about ourselves and our personality traits. 4 For example, self-help books, like Reading People by Anne Bogel, laud the power of personality tests to help us better understand ourselves and our relationships, arguing that we are motivated to take even the silliest of quizzes because “we truly want to know more about ourselves and the people we interact with every day.” 5 Devon Maloney suggests that our enjoyment of personality quizzes comes from the certainty that they promise in uncertain times. 6 This desire explains the widespread appeal of astrological signs, love languages, and Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) tests—despite a lack of evidence verifying their accuracy. There is a pleasure in being able to say something like “I had a real Pisces moment this morning,” or “I’m an ‘acts of service,’ while he’s a ‘words of affirmation,’” or “As an INFJ, I hate doing that sort of thing,” because these neat categories offer us certainty, an understanding of who we are and an explanation of why we do what we do. 7

While my purpose is not to litigate the accuracy of personality quizzes, it is worth noting that the efficacy of even the more serious and more popular personality tests has been brought into question. For example, there has been considerable and well-founded skepticism about the Meyer-Briggs Type Indicator—one of the most widely taken personality tests. Drawn from Jung’s types, the quiz is based primarily on folk psychology—more reflective of common beliefs about personality than anything empirically proven. 8 In addition, since 1956 when Paul Meehl coined the term, psychologists suggested that what is referred to as the “Barnum Effect”—named for “P. T. Barnum, a famous circus owner whose formula for success was always to have a little something for everybody” 9 —explains people’s general willingness to perceive the characterizations of zodiac signs and results of personality tests as largely accurate, aligned with and reflective of how they see themselves. As D.H. Dickson and I.W. Kelly assert in their 1985 meta-analysis, the Barnum Effect identifies the “psychological phenomenon whereby people accept general personality interpretations (Barnum profiles) as accurate descriptions of their own unique personalities.” 10 According to Dickson and Kelly, Barnum statements tend to be favorable, vague, applicable to almost anyone, or inherently contradictory 11 --not unlike the wording of many of the Buzzfeed personality quiz results we encounter which make broad, largely positive claims about the kind of people we are. Nevertheless, these statements often feel true because “the wording allows the subjects to project their own interpretations onto them.” 12 The actual accuracy of the results don’t matter as much as the fact that we perceive them as accurate, mapping out how we see (or would like to see) ourselves onto the description they provide.

My interest, then, is not in the reliability or accuracy of these quizzes. In fact, I don’t think that accuracy is actually all that important. Of course, we aren’t turning to Buzzfeed to learn deep truths about our most secret selves by designing our dream home, planning our perfect date, or building an ice cream sundae. But, even though we know that they are unscientific at best, complete nonsense at worst, we still take these quizzes, sharing, referencing, and interpreting our results. For me the question is not what the results of these quizzes say about us, but how we make sense of the results we get from them—and why we enjoy them so much. In a 2014 interview with Wired Magazine, media scholar Sherry Turkle theorized that we feel compelled to take a quiz listed on Buzzfeed or shared with us by our friends, because it “gives people something to look at, an object to think with. I think these quizzes are a kind of focus for attention for thinking about yourself.” 13 I want to interrogate what it means to think about ourselves with and through these quizzes, how they function as a cognitive tool for identity play.

We make meaning of our quiz results through an unconscious mental phenomenon referred to as conceptual blending, mapping the answers we receive onto our understanding of ourselves. The pleasure of these quizzes is not that they reveal something about us, but rather when we get our results, we are invited to construct a counterfactual blend in which we are cast into or as the fan-object. We, however briefly, imagine what it would be like to attend Hogwarts, date Jughead, or be a member of House Stark. By casting ourselves into these roles, we experience the pleasure of conceptualizing different versions of ourselves. These quizzes are popular and fun not because of the psychological insights they provide—what they say about who we are—but because they enact a brief fantasy through which we imagine different iterations of who we could be. They are a tool through which we play with who we could be, potentially integrating that identity into how we understand ourselves. It is not that they “reveal” our traits, but rather that we can use their results to shape how we conceptualize our personalities.

In this way, personality quizzes enable us to perform identity. Other scholars have asserted that these quizzes are performative, though not in the same way that I am. For example, Turkle suggests that these quizzes are “specifically for performance. Here, part of the point is to share it, to feel 'who you are' by how you share who you are.” 14 In addition, Stephanie N. Berberick and Matthew P. McAllister, argue that these kinds of quizzes function as a mode personal “branding” on social media sites: “Quiz responses are not right or wrong, but purportedly declare something about the quiz taker, whether about the perceived applicability of the results themselves to the taker’s interests or personality, or the spirit of fun and community in which quizzes are located.” 15 I argue that these quizzes are performative, but they are not a depiction of identity, but rather are generative of identity. They are performative in the way that J.L. Austin understands the word—they do something to, change something about, our identity and the way we see ourselves. 16 By thinking through them, we enact and play with who we are, casting ourselves as different characters and into new roles.

These quizzes don’t represent our identity; rather, by thinking with them, we are invited to enact and construct our identity. As Emre explains, one of those common beliefs of personality inventories like the Myers Briggs, is that our personalities are “an innate characteristic, something fixed since birth, like blue eyes or left-handedness.” 17 They are predicated on the idea that we have stable traits that these tests and inventories capture. However, as psychologists Richard Gerrig and David N. Rapp note, empirical research does not bear out our belief that our behavior is determined by set personality traits. This results in what is referred to as “the consistency paradox”: as they explain, “Although personality psychologists have produced ample evidence that traits do not predict behavior, other research evidence strongly suggests that people nonetheless rely rather heavily on trait assessments to make behavioral predictions.” 18 We want to believe that behavior is based on consistent traits—and that uncovering those traits through personality tests will help us to better understand ourselves and others—but the science doesn’t support that this is what actually happens.

Research in cognitive science and philosophy suggests that we experience our personalities as innate and unchanging, not because they actually are, but because we actively construct a conceptualization of them as though they are stable and consistent. In The Way We Think, Fauconnier and Turner explain we do this through an unconscious cognitive process referred to as conceptual blending, through which we make meaning by integrating different mental spaces—“small conceptual packets”—by mapping connections between them, selectively projecting information, and creating new mental spaces through which new concepts and understanding emerges. 19 The meaning generated by the new mental space is not in either of the in-put mental spaces but is structured and constructed through their integration.

The process of conceptual blending is essential to how we construct our understanding of characters—including ourselves. As Faucconier and Turner theorize, we understand the individuals we encounter in our everyday social and textual interactions through a process of selective projection. We notice and project patterns of behavior--extracting “regularities from over different behaviors by the same person”—and selectively projecting some and dropping others into a mental space for that character. 20 As Turner explains in The Literary Mind, “Someone who is typically in the role of adversary can . . . be thought of as ‘adversarial.’ He acquires a character: ‘adversarial.’” 21 Although this person is likely not always adversarial, we construct an understanding of his character as such by selectively projecting the times he is antagonistic into the mental space and dropping the times that he is affable or agreeable. It is not that traits cause behavior, but that we extrapolate traits from behavior.

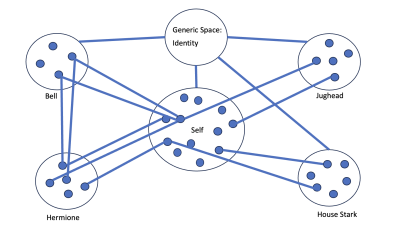

How do we construct different versions of ourselves from and through these quizzes? Conceptual blending can help us here as well. First, as we select our responses to the quiz questions, we are often asked to construct a version of ourselves through our answers, identifying as an introvert or extrovert, picking the words our friends would use to describe us, the image that best captures our energy, or our favorite movie or musical artist. Through this process, we project from and add to the mental space through which we conceptualize our character. Then, as we read the results, we map connections between the result we got and how we perceive ourselves, selectively projecting traits from each into a blend through which we understand ourselves in that role (Fig. 1). Through this process, we highlight certain perceived characteristics of who we are and drop others, which is how we can get a range of responses and think “Yes! That’s exactly me. I am a Hermione-Belle,” or “Jughead is perfect for me,” or “I would definitely be a Stark.” It is not that each of these results provides me with insight about who I am; as the Barnum Effect suggests, the descriptions in these results are written broadly enough that it could be about almost anyone or favorably enough that I am flattered into agreeing with them. And taken together, they create a somewhat incompatible amalgam of personality traits. But that doesn’t matter, because as we take each of these quizzes, we map the answers we got to our perception of ourselves and project them into a new blended space, thereby generating different versions of who we are.

[Figure 1]

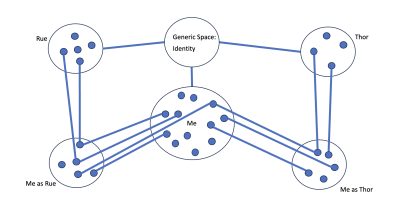

For this reason, I believe it is productive to think of these quizzes not in terms of branding, 22 but as casting. According to cognitive humanist Amy Cook, a “casting director may match the perceived qualities of an actor with perceived qualities of the character, but the combination is also synergistic; casting a character creates qualities.” 23 For this reason, she argues that casting is a “performative act in the sense that characters come to life once they are cast. Hurling an actor into a role creates a character.” 24 Something similar, I argue, happens when we take a personality quiz. We cast ourselves as the characters from The Avengers or The Hunger Games, creating new versions of ourselves as we imagine ourselves as them and compress our identities with theirs, generating a new identity blend (Fig. 2). Understanding myself in terms of Marvel’s Thor (“very bold,” “beautiful” and “intimidating” according to Buzzfeed 25 ) creates a very different version of myself than The Hunger Games’s Rue (“sweet and sensitive,” “likable,” “smart and caring”). 26 By reading these results, I get to try on these different versions of myself. The pleasure of these quizzes is not what they tell us about ourselves, but the way in which they enable us to cast ourselves into new roles and generate different iterations of the self, which may, but do not have to be, integrated into how we perceive our characters. Eventually, we might begin to typecast ourselves, expecting results that align with our conceptualizations of our personalities.

[Figure 2]

If, as I argue, we conceptualize our characters by casting ourselves as characters, why are characters so powerful when it comes to understanding our personalities? Traits are essential to how we understand characters, an integral part of how their identity blend is constructed. When we conceptualize someone as being “adversarial,” it is because we cast them as an adversary, giving them a role and creating a character out of the data points provided to use through their behavior. We develop character blends as a way to think about ourselves and each other, compressing diffuse behaviors into personality traits, which we then use to explain behavior. As Turner explains, “We develop an expectation that he will be ‘true to his character’: his character will guide his actions; his being will lead to his doing. We become primed to see him inhabit similar roles in other stories. ‘That’s just like him,” we say. Our sense of someone’s general character guides our expectations of which roles they will place in which stories.” 27 Once we cast someone as an “adversary” or an INF or House Stark or a Thor-type, we expect them to act in a certain way.

And the more specific the character, the more data points we can map and integrate through it. As Cook explains, “Character is a way of organizing into memorable units the large amount of stimuli,” 28 compressing different behaviors into something more manageable. Just saying a character’s name entails specific characteristics—and the roles and behaviors associated with them. 29 Through the process of blending and compression, Cook argues, “Humans have an ability to develop a ‘mental space’ called ‘Hamlet’ or ‘Odysseus’ that can be primed or brought to bear at any moment and that carries associations about what that character means.” 30 These mental spaces are not passively received, but are constructed through the dynamic integration of a network of behaviors into a conceptualization of a character. Characters are shared cultural touchstones—especially within fan communities. The reason why people tell each other, “I’m such a Miranda or a Samantha or a Charlotte” is because each of these women represented a clear type, associated with a specific set of traits and behaviors. Anyone familiar with Sex and the City is aware of the entailments of each character know what identifying as one of these characters is shorthand for: the smart type, the promiscuous type, the romantic type. In this way, characters are, according to Faucconier and Turner “basic cognitive cultural instruments.” 31 Through these quizzes, characters become, as Turkle says, a tool for “thinking about yourself” 14 as we play with our identities by casting ourselves as them.

More than that, though, characters enact stories. By linking results to specific characters, these data points about us become narratives that we can use to think about ourselves. As we think about our results, as we cast ourselves into different worlds and as different characters, we are encouraged to create counterfactual blends. Counterfactuals blends, Fauconnier and Turner explain, are conceptual blends that enable us to “operate mentally on the unreal.” 32 We conceptualize “What if” through “advanced conceptual blending” in order to construct a mental space that “has a forced incompatibility with respect to a space we take to be ‘actual.’” 33 I do not live in the fantasy medieval world of Game of Thrones, or the magical castle of Hogwarts, or even the wealthy, glamorous New York of Sex and the City, but the results from the quizzes invite me to imagine what it would be like if I did.

The construction of some of these quiz questions is oriented around this fantasy. For example, “Which ‘Game Of Thrones’ House Were You Destined To Be In?” consists of questions that require the taker to imagine what they would be like if they were in the medieval fantasy world of Westeros in which the series is set. Fans are given a list of famous quotes to take as their “house words”—the often-aspirational motto of each of the noble families in the series. They are asked to decide their weapon of choice, which Westerosi dish or drink they would reach for first at a feast, and what political strategy they would use to ensure the survival of their House. To answer these questions, fans have to create a counterfactual narrative in which they cast themselves into that world—blending what they know of themselves with what they know of Game of Thrones and creating a mental space in which they are living in that culture and setting. The answer they get continues this fantasy and identity play, inviting them to cast themselves as members of one of the great houses of the series.

This fantasy may be disrupted, though, if our results don’t align with what we thought we should get, if we can’t map connections between the mental space we have generated for and through which we understand ourselves and the Game of Thrones house or Riverdale guy we got. Despite the Barnum Effect, there are times when our results don’t seem to fit, where the role we are assigned doesn’t feel right; in short, we feel we have been miscast, unable or unwilling to construct a version of ourselves in that role. This is not to say that these quizzes are any less accurate, but that we construct less meaning from them. This feeling of miscasting might also arise when we don’t take pleasure in the role or character the quiz assigns us because of our fannish experience of the show and our affective attachments to certain characters. I might be disappointed to be told that the Marvel Avenger I am most like Thor because I like Iron Man better, so I experience more pleasure mapping connections between and casting myself as that character. Had Buzzfeed told me that Archie was the perfect Riverdale beau for me, I would have been disgruntled because he is not my Riverdale crush and that’s not the counterfactual narrative I desire to be inserted into; I want to be cast as Jughead’s girlfriend, not Archie’s. In such cases, I might retake a quiz to get a response that feels more “right” or that encourages the counterfactual narrative I desire. Our desire for alternatives and willingness to retake quizzes to attain them demonstrates that these quizzes are pleasurable not because of what they reveal, but rather through the fantasy they invite.

While I am specifically discussing Buzzfeed-style quizzes, it is worth noting that other, seemingly more serious tests, also invite a kind of casting. For example, the different personality types outlined by Myers-Briggs are associated with different roles: the Mediator (INFP), the Architect (INTJ), the Entertainer (ESFP), for example. While not the specific characters we might get from a Buzzfeed quiz, these roles provide us with a cognitive frame—skeletal cognitive structures—through which to understand our identity, functioning as a convenient shorthand for conceptualizing ourselves. As Fauconnier and Turner (2002) explain, “frames themselves may be . . . substantially linked to characters.” 34 The frames mediator, architect, entertainer come preloaded with a set of characteristics and entailments, their meanings compressed through the specific type. By labeling INFJs as “Advocates,” the Meyers-Briggs focused website 16Personalities is giving us a frame both through which to understand that personality type and to slot ourselves into if we are assigned that type. They might be more generic characters than finding out what Bob’s Burger or Star Wars character you are, but they are still characters, roles that we cast ourselves into in order to generate a conceptualization of ourselves.

In addition, many websites that explain these personality types also provide examples of specific characters—real and fictional—that demonstrate the respective clusters of character traits. According to 16Personalities, “Advocates You Might Know” include celebrities, like Nicole Kidman and Lady Gaga, historical figures, like Martin Luther King Jr. and Goethe, and fictional characters, Jon Snow (Game of Thrones), Matthew Murdoc (Daredevil), and Aragorn (Lord of the Rings). These characters serve as tools to think about the traits that the MBTI associates with INFJs, compressing defuse traits through specific identities. They rely on the same cognitive strategy that Buzzfeed does when it tells us which Avenger or Disney Princess we are. And also like Buzzfeed quiz results, they invite fans of Game of Thrones or Daredevil or Lord of the Rings to experience the pleasure of mapping connections between the self and beloved characters.

Personality quizzes on Buzzfeed are about play. But they are also tools through which we think about ourselves and can build a conceptualization of ourselves. As Turner notes, blended spaces can reflect back on and affect our conceptualization of in-put spaces. 35 In this way, taking these quizzes can help us to understand ourselves, not because the results we get from them reflect anything about us, but because we integrate their results into our understanding of ourselves. Through these quizzes we cast ourselves into fictional worlds and as fictional characters, mapping connections between how we view ourselves and what our results say, making sense of ourselves in those terms. Sometimes, we can’t map connections, and we might dismiss the results, marveling at how wrong the quiz got us. We're able to laugh off those results, because these quizzes do not “reveal” anything about us. If they help us to understand ourselves, it is because we generate and play with our identities through them, integrating aspects of our results into our conceptualization of ourselves.

Footnotes

Christina Ro. “Everyone Is 50% Disney And 50% Harry Potter Character--Who Are You?” Buzzfeed, 13 April 2019. https://www.buzzfeed.com/crystalro/which-disney-harry-potter-characters-are-you.

Chelsea Totten. 2020. “Tell Us What You Look For In A Partner And We’ll Tell You Which ‘Riverdale’ Guy You’d End Up With.” Buzzfeed, 21 January 2020. https://www.buzzfeed.com/chelseatot/describe-your-perfect-match-and-well-tell-you-whi-76nvu8bgry.

Thetattooprincess. “Which ‘Game of Thrones’ House Were You Destined To Be In?” Buzzfeed, 12 July, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/katiemckenna206/which-house-from-game-of-thrones-would-you-be-in-f78n.

Merve Emre. The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing (New York: Doubleday, 2018), xvi-xix.

Anne Bogel. Reading People: How Seeing the World through the Lens of Personality Changes Everything, (East Fulton: Baker Books, 2017), 12.

Devon Maloney. “Our Obsession with Online Quizzes Comes from Fear, Not Narcissism.” Wired. 6 March 2014. https://www.wired.com/2014/03/buzzfeed-quizzes/.

Emre, Personality Brokers, xvi-xvii.

Emre, Personality Broker.

D.H.Dickson & I.W. Kelly. “The ‘Barnum effect’ in personality assessment: A review of the literature,” Psychological Reports, 57, no 2 (1985): 367–382. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1985.57.2.367

Dickson, & Kelly, “The ‘Barnum effect,’” 367.

Dickson, & Kelly, “The ‘Barnum effect,’” 367.

Dickson, & Kelly, “The ‘Barnum effect,’” 369.

Quoted in Malony, “Our Obsession.”

Quoted in Malony, “Our Obsession.”

Stephanie N. Berberick and Matthew P. McAllister. “Online Quizzes as Viral, Consumption-Based Identities.” International Journal of Communication, 10 (2016): 3424. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5265.

J.L. Austin. How to Do Things with Words. Edited by J.O. Urmson. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016).

Emre, Personality Brokers, xvi.

Richard J. Gerrig & David N. Rapp. “Psychological Processes Underlying Literary Impact.” Poetics Today 25 (2004): 272. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-25-2-265.

Gilles Fauconnier & Mark Turner. The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 40.

Faucconier & Turner, The Way We Think, 251.

Mark Turner. The Literary Mind: The Origins of Thought and Language. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), 133.

Berberick & McAllister, “Online Quizes.”

Amy Cook. Building Character: The Art and Science of Casting. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018), 2.

Cook, Building Character, 2.

Matthew Perpetua. “Which Avenger Are You?” Buzzfeed, 2 May, 2015, https://www.buzzfeed.com/perpetua/avengers-age-of-ultron-quiz.

VioletTiger. “Which ‘Hunger Games’ Character Are You Most Like?” Buzzfeed, 26 April, 2019. https://www.buzzfeed.com/violettiger/which-hunger-games-character-are-you-4p0oia739f

Turner, Literary Mind, 133.

Cook, Building Character, 4.

Cook, Building Character, 49-53.

Cook, Building Character, 118.

Faucconier & Turner, The Way We Think, 250.

Fauconnier & Turner, The Way We Think, 217.

Faucinnier & Turner, The Way We Think, 230.

Fauconnier & Turner, The Way We Think, 253.

Turner, Literary Mind.

References

Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words. Edited by J.O. Urmson. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016).

Berberick, Stephanie N. and McAllister. Matthew P. “Online Quizzes as Viral, Consumption-Based Identities.” International Journal of Communication, 10 (2016): 3424. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5265.

Bogel, Anne. Reading People: How Seeing the World through the Lens of Personality Changes Everything. East Fulton: Baker Books, 2017.

Cook, Amy. Building Character: The Art and Science of Casting. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018.

Dickson, D.H. & Kelly, I.W. “The ‘Barnum effect’ in personality assessment: A review of the literature,” Psychological Reports, 57, no 2 (1985): 367–382. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1985.57.2.367.

Emre, Merve. The Personality Brokers: The Strange History of Myers-Briggs and the Birth of Personality Testing. New York: Doubleday, 2018.

Fauconnier, Gilles & Turner, Mark. The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Gerrig, Richard J. & Rapp, David N. “Psychological Processes Underlying Literary Impact.” Poetics Today 25 (2004): 272. https://doi.org/10.1215/03335372-25-2-265.

Maloney, Devon. “Our Obsession with Online Quizzes Comes from Fear, Not Narcissism.” Wired. 6 March 2014. https://www.wired.com/2014/03/buzzfeed-quizzes/.

Perpetua, Matthew. “Which Avenger Are You?” Buzzfeed, 2 May, 2015. https://www.buzzfeed.com/perpetua/avengers-age-of-ultron-quiz.

Ro, Christina. “Everyone Is 50% Disney And 50% Harry Potter Character--Who Are You?” Buzzfeed, 13 April 2019. https://www.buzzfeed.com/crystalro/which-disney-harry-potter-characters-are-you.

Thetattooprincess. “Which ‘Game of Thrones’ House Were You Destined To Be In?” Buzzfeed, 12 July, 2017. https://www.buzzfeed.com/katiemckenna206/which-house-from-game-of-thrones-would-you-be-in-f78n.

Totten, Chelsea. 2020. “Tell Us What You Look For In A Partner And We’ll Tell You Which ‘Riverdale’ Guy You’d End Up With.” Buzzfeed, 21 January 2020. https://www.buzzfeed.com/chelseatot/describe-your-perfect-match-and-well-tell-you-whi-76nvu8bgry.

Turner, Mark. The Literary Mind: The Origins of Thought and Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

VioletTiger. “Which ‘Hunger Games’ Character Are You Most Like?” Buzzfeed, 26 April, 2019. https://www.buzzfeed.com/violettiger/which-hunger-games-character-are-you-4p0oia739f.