Abstract

While she is so often embodied in her poetry, Lucille Clifton, known spiritualist and “two-headed woman,” is equally disembodied, a messenger for the deceased, disavowed, and oppressed. She speaks through and for others, both figuratively as a craftswoman employing personas, and literally as a medium engaging with the words of the dead. In doing so, Clifton has given voice to those who cannot speak: biblical characters, historical figures including Crazy Horse and Emily Dickinson, her own departed family members, and, as this paper explores, the popular food packaging icons Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and the original Cream of Wheat mascot (known popularly by the derogatory name Rastus). I argue that Clifton’s black feminist mediumship is parallel to her voicing of food packaging icons by exploring the interplay of voice and body in her final collection, 2008’s Voices. Clifton’s voicing is indeed a feminist act and one that does not contradict her embodied experiences of race, gender, and disability.

Recipient of the Ralph Donald Award for Outstanding Paper. Originally presented in the Black Studies Area of the Annual Conference of the Mid-Atlantic Popular & American Culture Association. November 2024, Atlantic City, NJ

Content Warning: I believe in content warnings, as I always want to be respectful and aware of how the content I teach, write about, and discuss may affect people. That is particularly true when speaking from a voice of scholarly expertise but not lived experience, such as in this paper (which I, a white woman, originally presented on a Black Studies panel). Therefore, please know that this paper discusses vintage food advertisements that have racist depictions of black women and men; while they do not use racial slurs, they do use racist dialect.

In previous scholarship and teaching, I have written and talked at length about the understudied but profoundly important 20th century American poet and writer Lucille Clifton: how she uses John Milton’s Eve and Lucifer characters as jumping off points for her own biblical interpretations, how she evokes the moon in relation to lycanthropy and menstruation, and how she redefines the body in regard to gender, race, and disability. 1 These discussions and projects share a focus on how Clifton is grounded in her physical body: as a woman who was black and fat, as a mother and wife, and as someone who had disabilities and encountered serious illness. In so doing, the projects explore the intersections of these subject positions and how they inform the different parts of Clifton’s identity in order to make a complete person.

Here, I build on that scholarship to examine a different aspect of the poet’s legacy: Clifton as embodied disembodiment in her mediumship and persona writing. I focus on the 2008 collection Voices, which was Clifton’s last book of poetry before her death in 2010 and, specifically, how Clifton’s mediumship and spirit writing connect to her persona writing by focusing on three poems in which she speaks through the voices of black food advertising mascots: “aunt jemima,” “uncle ben,” and “cream of wheat.” 2

Throughout her long career as a poet, Lucille Clifton frequently wrote through the mouths and bodies of others, communicating with spirits as a medium and adopting personas in her poems. In both ways, she was a mouthpiece for those who could not speak, whether because those she voiced were deceased, fictional, or otherwise silenced. She spoke regularly for biblical characters, historical figures and poets, and her own deceased family members. This voicing furthers Clifton’s legacy as a feminist poet. While poems such as “homage to my hips” and “poem in praise of menstruation” built her reputation as a feminist poet who celebrated the realness of the female body, the poems in which she inhabits the bodies of those less empowered to speak concretize her writing as distinctly feminist in a way that is intersectional, empowering, and unbound by constraints such as time and embodiment.

As Marina Magloire discusses in her important work on Clifton’s spirit writing, some scholars have identified this idea of talking through others as a central fracture in Clifton’s opus: she is known for being a poet in a body who writes specifically about her bodily experiences, and yet so often she exists in her poetry as a voice unbound by her own physical form. Magloire pushes back on the idea that this is a fracture—rightly so—stating that to make this argument is to misinterpret Clifton’s poetry. 3 My intervention in this discussion looks at Clifton’s black feminist mediumship as parallel to her voicing of notable historical and popular culture figures. In the three poems analyzed here, the interplay of voice and body serves as a means for Clifton to amplify her own experiences and the voices of those often unheard.

Clifton was part of a “long and storied tradition of Black American women endowed with spiritual powers.” 4 Using terms traditionally associated with African-American spiritual practice, Magliore describes them as “rootworkers, two-headed women, and hoodoo women,” 5 and explains that “the trope of the clairvoyant Black woman has existed as long as Black women have been in the Americas, but had experienced a renaissance in the last decades of the twentieth century.” She offers many examples of literary and popular culture iterations, but the most well-known is likely Oda Mae Brown, the character played by Whoopi Goldberg in the 1990 film Ghost. 6

As no one has offered Clifton scholars more about the poet’s “two-headedness” than Magloire, whose article “Some Damn Body”: Black Feminist Embodiment in the Spirit Writing of Lucille Clifton” picks up on and expands the sparse earlier work on the topic, I will lean a bit more on Magloire for background here. Magloire recognizes that her work “is the first to analyze Clifton’s vast unpublished archive of spirit writing as a central part of her life and poetry—not as a metaphor or as a sidebar, but as a body of work ‘emanating from an astute, profound intellect.’” 7 The article details how Clifton began using a Ouija board in 1976 and how, within a few years, the spirit of Clifton’s long deceased mother became a frequent visitor in the Clifton household. For years, Clifton, her six children, and, to a lesser extent, her husband Fred, communicated with the dead “sometimes as automatic writers, sometimes as interpreters for non-English-speaking spirits, and sometimes even channeling the voices of spirits through their own bodies.” 8

Magloire’s central argument is one worth highlighting:

[I]n Clifton’s writing, Black womanhood is represented as particularly fruitful ground for this kind of spiritual partnership, to serve as a lightning rod for everyone else’s electrified narratives and desires. . . . [T]here is no indication [in her writing] that souls are attached to the particularities of their bodily incarnations. But, following Clifton’s own theory, the fact that her soul has selected this particular body in which to exist illustrates the particular lessons that being a Black woman can teach. If a Black woman’s soul is her own society, it follows that a soul, not beholden to contingent social constructs like race and gender, has the capacity to change those constructs. 9

Magloire’s argument about Clifton’s black feminist mediumship can and should be extended to Clifton’s voicing of historical and popular culture icons, because, when writing in this persona, she is equally radical and equally feminist, and, I argue, just as empathetic. Clifton is absolutely speaking from her own voice, her own ancestry—historically oppressed and silenced subject positions—while she voices these personas. This voicing is an act that does not contradict her embodied experiences of race, gender, and disability, but is instead possible only through them.

aunt jemima

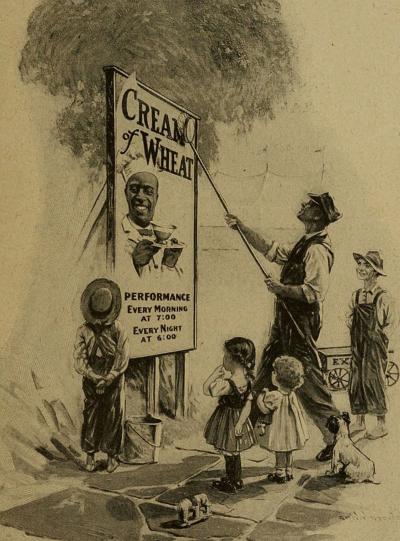

In “aunt jemima,” Clifton writes as the persona of the breakfast mascot created by the R.T. Davis Milling Company in the late 19th century to help sell their pancake mix; in 1893 they rebranded it as the Aunt Jemima pancake. In early advertisements, Aunt Jemima was portrayed by Nancy Green, a “formerly enslaved woman hired by the R.T. Davis Company to play the role of Aunt Jemima at events across the United States.” 10 With her slogan, “I’se in town, honey!” Aunt Jemima was portrayed as uneducated but jolly, as seen as Figure 1. Born out of a minstrel song and the deep-seated and dark history of racism in the United States, Aunt Jemima was rooted in slavery and “connected white consumers’ romanticized view of the ‘Old South’ with their easy-to-make homemade pancakes.” 11

Figure 1: Aunt Jemima's Pancake Flour Advertisement (R.T. Davis Mill Company, 1894)

In her final interview, Clifton says that in Voices, she was “interested in naming, and calling things by their names” and rhetorically asks, “What makes us arrogant in believing that we have the accurate name” for people and things? Speaking of the poem “aunt jemima” specifically, she recalls,

I was thinking about those names that we hold dear, and we take for granted. These are in their voices, and I do voices I think pretty well. Or well enough, at any rate. This is called “aunt jemima.” She is speaking. 12

Clifton/Jemima begin the poem, “white folks say i remind the /of home,” 13 immediately calling readers’ attention to the nation’s history as a slave-holding country and insinuating that many still romanticize or even long for the time of slavery; to them, an antebellum U.S. is a return home or return to tradition. Jemima herself has, of course, been “homeless / all [her] life except for their / kitchen cabinets,” 14 an image which positions her as an enslaved woman shackled to white women’s kitchens. She laments for herself, her dreams, and all the time she has lost serving others, and wonders about her “true” nephews and nieces, her own family, and her own home. Here, Jemima and Clifton overlap again; Jemima bears the weight of her enslavement while Clifton looks to the reverberations from slavery that have been felt by generations of Black Americans. 15 Further blurring the lines between Clifton and Jemima, there is a clear parallel between this and Clifton’s well-known poem “won’t you celebrate with me”:

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand 16

This is echoed in “aunt jemima” when Jemima says,

i who have made the best

of everything

pancakes batter for chicken

my life 17

"uncle ben"

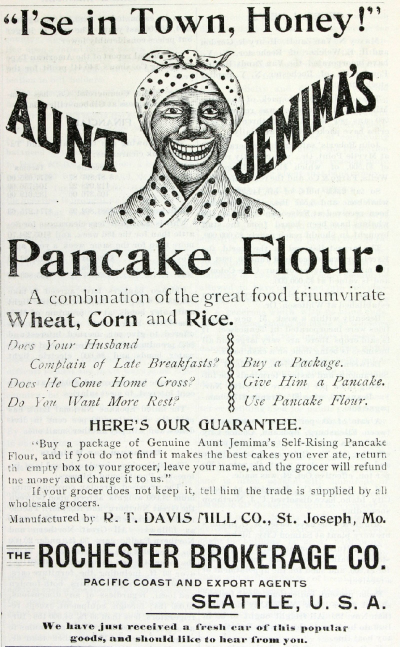

Figure 2: Uncle Ben's ad from the Ladies Home Journal, May 1951

Immediately following “aunt jemima” in Voices is “uncle ben,” whose subject is the famed Uncle Ben’s Rice mascot (rebranded Ben’s Original in 2020 in order “to signal [the brand’s] ambition to create a more inclusive future while maintaining [their] commitment to producing the world’s best rice” 18 ). From 1946 to 2020, Uncle Ben's products carried the image of an elderly black man dressed in a bow tie, seen pictured in Figure 2. Uncle Ben was said to have been based on a Chicago maître d' named Frank Brown, with the name "Ben" being a possible reference to a rice farmer from Houston. 19 Like Aunt Jemima, the Ben’s brand name and image “reflect the practice of white Southerners addressing elderly African-Americans as ‘uncle’ and ‘aunt’” rather than using the more respectable honorifics of “Mr.” and “Mrs.” 20

The heart-wrenching poem tells of a man stolen from his homeland in Africa and forced to labor in a rice patty:

rice rice rice

and so he worked the river

worked as if born to it

thinking only now and then

of himself of the sun

of afrika 21

His identity as a “favorite son” of Africa is displaced through enslavement and he becomes a lost soul who knows “not where he was / not why.” 22

Interestingly, when introducing the poem in her interview with Grace Cavalieri, Clifton says, “This is called ‘uncle ben,’ and he is talking.” 23 Despite this claim, Ben does not appear to be the poem’s speaker as evidenced by the repeated use of third-person he/him pronouns. The poem’s speaker, Clifton or someone else, instead appears to be speaking about Ben’s experience as an outside observer. An alternative interpretation might read Ben as the speaker but, were that the case, it would mean that the poem is not about Ben’s own experiences but someone else’s, a reading that seems contradictory to both the poem’s title and its content. Clifton’s statement perhaps reveals then the shared embodied voice of speaking both as oneself and for another simultaneously. As in “aunt jemima,” here Clifton also suggests a dual or shared voice and perspective.

Rachel Elizabeth Harding points to an “alternative orientation” in Clifton’s poetry, explained as “the historical necessity among African Americans, as an oppressed people, to create and sustain ‘an-other’ way of understanding their place in the world.” 24 Clifton is particularly qualified to speak for figures like Ben, part mythology / part living historical figure, because of both her connection to the spirit world and her lived experience as a poet of color. Because Ben is unable to “create and sustain” an alternative way of understanding his place in the world, Clifton steps in and writes his story in a way that requires a unique voice of color to do so.

"cream of wheat"

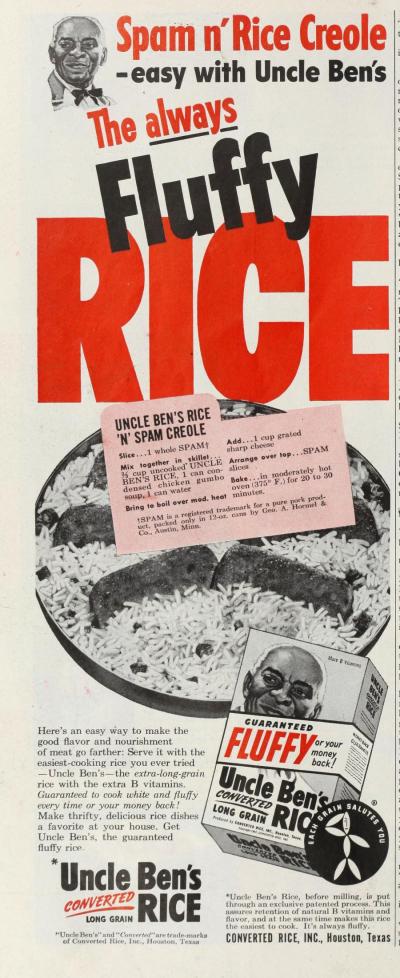

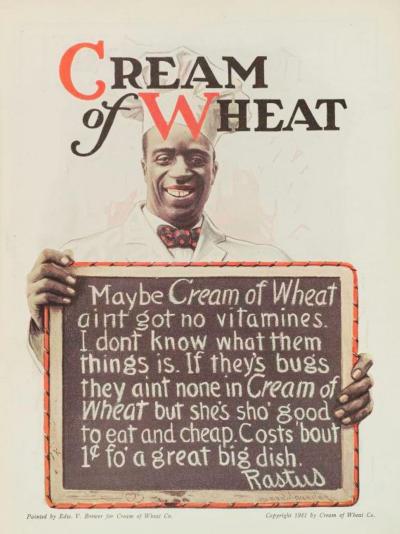

Finally, “cream of wheat” gives voice to the brand’s infamous hot cereal mascot, popularly referred to using the derogatory name Rastus. His image, created by artist Edward V. Brewer, was used on Cream of Wheat packages until 1920 when it was replaced by a photograph of Frank L. White, a black chef from Chicago. Rastus has been a stereotypical and derogatory name for black men at least since the late 19th century. Historically, the name referred to a stereotypically happy black man, not necessarily a particular person, and was a popular character in minstrel shows. 25 Figure 3 shows an offensive early 1920s advertisement which portrays the character as being unintelligent, evidenced by the spelling and grammatical errors in the sign he holds, and, like Jemima and Ben, there are also connotations of subservience as seen in the chef’s bright smile as he happily offers customers a meal “sho’ good to eat and cheap.”

Figure 3: Advertisement for Cream of Wheat. Used between 1901 and 1925, when the chef was replaced.

In Clifton’s poem, the mascot strolls the supermarket aisles at night with “ben and jemima” but feels separate from the pair and lags behind—this separation seems to be because of the void felt by the narrator in being nameless. While the speaker wonders at his name, and his supposed name does appear in the poem, Clifton enables him to refuse the racist moniker. The speaker laments his association with the name but asserts that he knows that “no mother ever / gave that [name] to her son.” 26 In fact, he ends the poem asking “what is my name”—angry, but sure that he must have one. That assertion speaks to his pride, knowing that he has value beyond what he offers in the grocery store. As he is a character and not real, he has no agency—but Clifton chooses to give him a voice and to use that voice to refuse a racist name.

As he walks behind his two contemporaries, he tries unsuccessfully to remove the chef’s hat that makes him recognizable. Here, he and Clifton tackle “[t]he issue of one's name as an essential component of personhood." 27 Without a name, he feels personless, an embodiment of Black subservience. While Clifton is unable to give him a new name, her refusal to accept a name they both acknowledge as offensive is important, and she is able to give him a voice to speak his anger. The sense in this poem is that Clifton knows his wishes intimately and advocates for him because he is unable. As Kaczmarek says, “in cream of wheat” and other persona poems, “Clifton beautifully illustrate[s] the processes by which silence finally breaks into language. 28

The three poems, though distinct, showcase how Clifton and the voices of these characters “overlap in a continuity of dreams and desires unfulfilled.” 29 Kaczmarek notes that

all three characters “pose and smile” but secretly “simmer” with dreams, desires, frustration, anger. Clifton reminds us that although these icons have been presented as acceptable for consumption, images of slavery [and subservience] are never innocent. By pretending that they are, these voices argue, we continue to participate in the silencing of those dehumanized by slavery and to ignore the residual effects of slavery in our culture today. 30

Grace Cavalieri writes that “This is the art that Lucille has cultivated her whole life – the persona poem . . . And in [these poems], look what she does with product placement. Look what she does with advertisement. In three poems, in less than fifty words, she takes on egregious, and painful subjects in American history. 31

Because Clifton’s minimalist style is so distinguishable, “distinctions among individual voices are not sharply demarcated; Clifton's characters echo one another visually and thematically.” 32 This supports my reading of an embodied Clifton at the helm of the persona poems. The interplay between voice and body in these poems show that Clifton is not a spiritualist or a persona writer who is disembodied—she is a black, female, disabled, etc. spokesperson for the dead and fictional people for whom she speaks. The masks she dons are transparent, with Clifton—voice and body—always coming through.

In 2020, amid widespread calls for food companies to address racist imagery in their branding, figures including Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and the Cream of Wheat mascot were removed from product packaging, either replaced with alternative branding or “retired” entirely by removing images of the characters from branding. Other companies, including the makers of Eskimo Pies and Mrs. Butterworth’s pancake syrup reevaluated and made notable changes to their names and packaging. In a New York Times article, USC cinema and media studies professor Todd Boyd noted that

When you talk about racism — structural, system and institutional — it’s never been just one thing . . . It’s representative of a society built around certain ideas and certain images. Taking the stereotypical image of a Black servant off the Cream of Wheat boxes isn’t going to end systemic racism tomorrow, but it’s part of a larger series of myths, thoughts and ideas that combined have the ability to change perceptions. 33

One might speculate how Clifton herself might have responded were she alive to see these changes. I strongly suspect that she would have seen them as a symbolic liberation from the mascots’ long-entrenched roles within the visual economy of American racial representation.

Footnotes

See “The Appropriation of an Epic: Lucille Clifton’s Feminist Retelling of Milton.” Feminist Spaces 3.1. Winter 2017, 79-95.

Clifton is known for sparse use of punctuation and using very few capital letters in her poems. In this paper, I follow her lead when referring to the poem’s titles and when quoting from the texts directly, but do capitalize proper nouns when discussing them otherwise.

Marina Magloire, “‘Some Damn Body’: Black Feminist Embodiment in the Spirit Writing of Lucille Clifton,” African Review 55, no. 4 (2022): 317–30 .

Magloire, “Some Damn Body,” 317.

These terms refer to the practice of "working roots" by traditional healers and conjurers of the rural, black South. For more, see the entry for “root workers” on NCpedia.

Magloire, “Some Damn Body,” 317.

Magloire, “Some Damn Body,” 317.

Magloire, “Some Damn Body,” 317-319.

Magloire, “Some Damn Body,” 318.

Women & the American Story, “Aunt Jemima.” https://wams.nyhistory.org/industry-and-empire/labor-and-industry/aunt-jemima/

Women & the American Story, “Aunt Jemima.”

Clifton, “The Last Interview: The Poet and the Poem.” Emphasis mine. https://www.gracecavalieri.com/significantPoets/lucilleClifton2.html

Clifton, “aunt jemima,” lines 1-2.

Clifton, “aunt jemima,” lines 2-4.

Clifton, “aunt jemima,” lines 12-17.

Clifton, “Won’t You Celebrate with Me,” lines 7-11.

Clifton, “aunt jemima,” lines 5-8.

“Our History | Ben’s OriginalTM.” https://www.bensoriginal.com/our-history.

BBC, “Uncle Ben’s Changes Name to More ‘Equitable’ Brand.” https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54269358

BBC, “Uncle Ben’s Changes Name to More ‘Equitable’ Brand.”

Clifton, “uncle ben,” lines 9-14.

Clifton, “uncle ben,” lines 1, 4-5.

Clifton,“The Last Interview: The Poet and the Poem.”

Harding, “Authority, History, and Everyday Mysticism in the Poetry of Lucille Clifton: A Womanist View,” 41.

Fazio, “Cream of Wheat to Drop Black Chef from Packaging, Company Says.” The New York Times, September 27, 2020, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/27/business/cream-of-wheat-man.html

Clifton, “cream of wheat,” lines 13-14.

Kaczmarek, “Choruses of Experience,” The Women’s Review of Books 26, no. 4 (2009): 21.

Kaczmarek, “Choruses of Experience,” 22.

Kaczmarek, “Choruses of Experience,” 21.

Kaczmarek, “Choruses of Experience,” 21.

Clifton, “The Last Interview: The Poet and the Poem.”

Kaczmarek, “Choruses of Experience,” 21.

Fazio, “Cream of Wheat to Drop Black Chef from Packaging, Company Says.”

References

Image Permissions:

Figure I: University of Washington, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2: Uncle Ben's Co., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Cream of Wheat advertisement, US Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Bibliography

BBC. “Uncle Ben’s Changes Name to More ‘Equitable’ Brand.” BBC News, September 23, 2020, sec. Business. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-54269358.

Ben’s Original. “Our History | Ben’s OriginalTM,” 2014. https://www.bensoriginal.com/our-history.

Clifton, Lucille. “The Last Interview: The Poet and the Poem.” Interview by Grace Cavalieri. Gracecavalieri.com. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.gracecavalieri.com/significantPoets/lucilleClifton2.html.

Clifton, Lucille . “aunt jemima.” In Voices, 12. Rochester: BOA, 2008.

———. “cream of wheat.” In Voices, 14. Rochester: BOA, 2008.

———. “uncle ben.” In Voices, 13. Rochester: BOA, 2008.

———. “won’t you celebrate with me.” In The Book of Light, 25. Rochester: BOA, 1993.

Conaway, Cameron. “Review: Voices by Lucille Clifton.” Rattle Poetry, January 30, 2009.

https://www.rattle.com/voices-by-lucille-clifton/.

Fazio, Marie. “Cream of Wheat to Drop Black Chef from Packaging, Company Says.” The New York Times, September 27, 2020, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/27/business/cream-of-wheat-man.html.

Harding, Rachel Elizabeth. “Authority, History, and Everyday Mysticism in the Poetry of Lucille Clifton: A Womanist View.” Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 12, no. 1 (2014): 36–57. muse.jhu.edu/article/541871.

Kaczmarek, Ginny. “Choruses of Experience.” The Women’s Review of Books 26, no. 4 (2009): 20–22.

Magloire, Marina. “‘Some Damn Body’: Black Feminist Embodiment in the Spirit Writing of Lucille Clifton.” African Review 55, no. 4 (2022): 317–30. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/afa.2022.0043.

NCpedia. “Root Doctors | NCpedia,” n.d. https://www.ncpedia.org/root-doctors.

Women & the American Story. “Aunt Jemima.” Accessed October 18, 2023.

https://wams.nyhistory.org/industry-and-empire/labor-and-industry/aunt-jemima/.