The term “manic pixie dream girl” was coined by Nathan Rabin in 2007 to call attention to female characters, particularly in film, who “exist solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.” 1 In his definition, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl exists in narratives solely to advance the male protagonist’s character arc. She does not have any kind of characterization or development of her own, aside from numerous quirks, and a personality so strong it could be confused for character development. Rabin initially cited examples of the trope as Kirsten Dunst’s Claire in Elizabethtown and Natalie Portman’s Sam in Garden State. In describing Dunst’s Claire as “an unusually pure example” of the trope, he called her “a fancifully if thinly conceived flibbertigibbet who has no reason to exist except to cheer up one miserable guy.” 2 Since then, the term has been applied to a number of female characters across all media, including film and literature. The trope seems highly prevalent in media targeted at teenagers and young adults, especially teen girls, although many of these media are written by men, and the narratives are often told from a male perspective.

While problematic, the trope does not seem to intentionally promote a misogynistic representation of women. Rather, it seeks to represent a different kind of femininity than the femininities often presented in popular media. While tropes such as the “queen bee” or “prom queen,” the “girl next door,” and the “warrior woman” are rather common, especially in media for adolescent girls and young women, the manic pixie dream girl attempts to create more complex, interesting female characters in these media who are attractive and interesting, while still being relatable and attainable for average male protagonists. This attempt, however, ultimately fails. Instead, the trope creates an unrealistic, fantastical ideal of white, middle-class femininity for boys and men to desire and girls and women to desire to be. Rather than using these characters to challenge constricting patriarchal demands on feminine behavior and appearance, the trope creates female characters who appear empowered, but continue to operate within the socially acceptable limits of femininity.

The manic pixie dream girl fits a formula surrounding the four descriptors “manic,” “pixie,” “dream,” and “girl.” As suggested by the term “manic,” manic pixie dream girl characters often engage in impulsive, unhealthy behaviors, including drinking, smoking, and problematic performances of sexuality for male pleasure, frequently in conjunction with mental illness of some kind. As “pixies” they also conform to cultural beauty standards and are considered very attractive and desirable by other characters in the narrative. The use of the term “dream” in describing these characters serves as a reminder that they were created to serve male fantasies, and that they only exist in one’s mind. “Girl” emphasizes the idea that these are immature, childlike characters—as opposed to “woman,” which would imply a stronger, more empowered character. It is also important to remember that not only are manic pixie dream girls the idealized creations of their authors, but they exist also as fantasies in the minds of the male protagonists who often narrate these texts.

Some texts, such as the novel Paper Towns by John Green, include characters who possess all of the features of the manic pixie dream girl, but challenge the trope by allowing the reader to try to imagine the character as a complex individual, thus shattering the fantasy of the manic pixie dream girl. Rather than idealizing the manic pixie dream girl character throughout the narrative, the male protagonists in these deconstructing texts learn to see her as a person, rather than the idea they originally projected onto her. As readers follow along on the male protagonist’s character arc, we come to learn the same lessons as he does.

On the surface, Margo Roth Spiegelman in Paper Towns appears very much like a manic pixie dream girl. She is very attractive and popular, and although he has not spoken to her in years, Quentin (also known as “Q”) claims that he is in love with her. In the prologue of the novel, Q claims, “My miracle was this: out of all the houses in all the subdivisions in all of Florida, I ended up living next door to Margo Roth Spiegelman,” thus introducing Margo as someone to idealize and fantasize about. 3 Later, he describes her as “so awesome, and in the literal sense,” and continues

She was the only legend who lived next door to me. Margo Roth Spiegelman, whose six-syllable name was often spoken in its entirety with a kind of quick reverence. Margo Roth Spiegelman, whose stories of epic adventures would blow through school like a summer storm. 4

The stories of those “epic adventures,” which include traveling with the circus for three days and sneaking into a concert by convincing the bouncer that she was the bassist’s girlfriend, add to Margo’s mystique and almost seem too good to be true, although Q claims that the stories have always turned out to be true.

The first part of the novel takes Q on one of Margo’s epic adventures. While it is not as exciting as her other escapades, it does reflect her behavior as a manic pixie dream girl. Margo climbs through Q’s window and brings him on the most exciting nights of his life as they exact revenge on a number of Margo’s former friends who have wronged her, go to twenty-fifth floor of the SunTrust Building after hours to enjoy the view, and break into SeaWorld. As Margo later explains, she brings Q with her in order to “push [him] toward being a badass.” During the prank night, she expresses her disdain for others’ concern for the future,

It amazes me that you can find that shit even remotely interesting … College: getting in or not getting in. Trouble: getting in or not getting in. School: getting A’s or getting D’s. Career: having or not having. House: big or small, owning or renting. Money: having or not having. It’s all so boring. 5

Margo’s claims here serve to critique Q, who is very focused on his future plans and career goals, which he has all figured out at the beginning of the novel. Her argument also helps to establish her character as disinterested in the future, and much more focused on her incredible, whimsical, seemingly impulsive adventures.

This behavior in Part One of Paper Towns establishes Margo as a manic pixie dream girl, although the remainder of the narrative works to deconstruct this vision of Margo and leads Q, and the reader, to imagine her more complexly as a person, rather than as the idea they see her as at the beginning. When Margo goes missing, Q takes it upon himself to find her. He takes a number of clues that Margo left behind, including a photo of Woody Guthrie, lines from Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” and the address to an abandoned strip mall, as evidence that she, indeed, wants him to go and find her. Through his investigation, Q projects his idea of Margo when trying to understand her well enough to find her.

Q’s failure to understand her leads him to repeatedly fail in his attempts. It is not until a conversation with his parents over dinner that he realizes his shortcoming:

But isn’t it also on some fundamental level we find it difficult to understand that other people are human beings in the same way that we are? We idealize them as gods or dismiss them as animals. 6

This line, spoken by Q’s mother, emphasizes the importance of attempting to imagine others more complexly as human beings.

In regard to Margo, she and other manic pixie dream girls are “idealized as gods” for their looks and their ability to breathe new life into the male protagonists they encounter, but they are never considered as people. As Q realizes this, he is able to change the focus of his investigation. In trying to understand Margo better, he is finally able to successfully put his clues together to determine where Margo has gone and that she is not going to come back. At this point, however, he still holds onto a small part of his idea of Margo—the idea that she wanted him to come and find her.

When Quentin does find her, the deconstruction of Margo as a manic pixie dream girl is almost complete. Margo’s anger functions to emphasize that Q still hasn’t fully separated Margo the idea from Margo the girl. She tells Q, “You didn’t come here to make sure I was okay. You came here because you wanted to save poor little Margo from her troubled little self, so that I would be oh-so-thankful to my knight in shining armor.” 7 While Q seems to have convinced himself that he no longer wants that, his entire search was driven by his feelings for her.

The most important moment to the deconstruction of the manic pixie dream girl in Paper Towns comes when we are finally allowed to see Margo’s side of the story. She is mostly absent through the middle of the book, from the end of the prank night until Q and his friends arrive at the barn where she is hiding. Toward the end, however, she explains her side.

I was the flimsy-foldable person, not everyone else. And here’s the thing about it. People love the idea of a paper girl. They always have. And the worst thing is that I loved it, too. I cultivated it, you know? Because it’s kind of great, being an idea that everybody likes. But I could never be the idea to myself, not all the way. 8

Margo constructed herself as a manic pixie dream girl for those around her, but she could not maintain the illusion for herself. While being a “paper girl” for others was enjoyable, she struggled to make herself real. This allows the illusion to be shattered not only for Q but for the reader as well, as we come to understand the harm that the prominence of the manic pixie dream girl myth can cause.

The film adaptation takes a different approach to the narrative of Paper Towns. While Green’s novel focuses primarily on the deconstruction of the manic pixie dream girl trope, Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber’s screenplay highlights Q’s relationships with the other characters and puts Margo on the back burner. It isn’t until the end of the film that Quentin addresses his misperception of Margo in a few brief lines of voice-over narration. In true manic pixie dream girl fashion, it seems that Quentin’s infatuation with Margo and Margo’s disappearance serve as a vehicle for the new story the filmmakers wanted to tell from this source material.

The film hits many of the same major beats as the novel—the revenge prank night; Margo’s disappearance; the discovery of clues that Margo left behind; Quentin’s subsequent obsession with finding her; the road trip from Orlando, Florida, to Agloe, New York; finding Margo; and Quentin learning to let go and leave Margo behind in Agloe—but it leaves out many of the key moments from the novel that lead Quentin to imagine Margo more complexly and help him see her as more than the mysterious girl across the street who he’s always had a crush on. When we reach the film’s denouement, which features an adaptation of Margo’s speech and Q’s realization that Margo was not the girl he had imagined her to be, it lacks the weight it carries in the novel. Without the focus on trying to understand Margo and imagine her as a person rather than a fantasy, it is hard to believe Quentin’s final realization that it is “a treacherous thing to believe that a person is more than a person,” an epiphany that comes much earlier in the book.

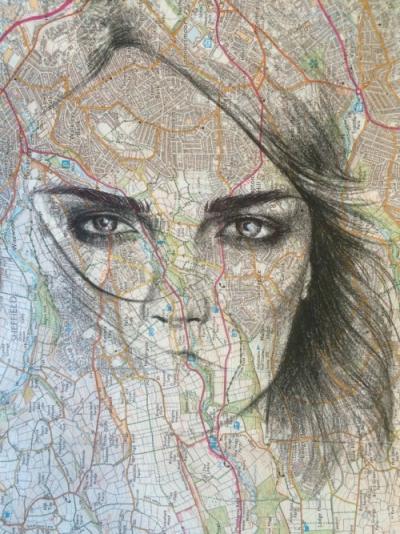

In the film, Cara Delevingne plays Margo Roth Spiegelman. Prior to Paper Towns, Delevingne was most well known as a model, most notably for Victoria’s Secret; as a member of Taylor Swift’s famous squad featured in her “Bad Blood” music video; and for her thick, iconic eyebrows, although she had appeared in some small television and film roles. Since Paper Towns, she has gone on to star in larger films, such as Suicide Squad and Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets. Casting a model in this role seems to add to the fantastical, larger-than-life persona of the character. In the novel, Margo’s physical appearance is not highlighted.

While Quentin acknowledges her beauty, he claims that her physical appearance gets wrapped up in the mystery around her:

You can’t divorce Margo the person from Margo the body. You can’t see one without seeing the other. You saw Margo’s eyes and you saw both their blueness and their Margoness. 9

In the film, Margo’s beauty is often front and center. Shots tend to linger on her, and she is frequently framed or lit in such a way that your focus is drawn to her over the other subjects on camera. Even in the film’s poster, we get a strong sense of Margo’s character. While she is prominently positioned in the photo, her hair obscures her face. The image gives off the air of mystery surrounding the character while still establishing her significance to the story.

Without the focus on Quentin learning to imagine Margo complexly, the film’s narrative theme appears to focus more on Quentin learning to appreciate those around him, and the film cuts back on its attention to Margo in order to give Ben, Radar, Lacey, and Angela more screen time. Most notably, Angela appears in the road trip in the film, while she was absent from it in the novel. This shift in focus, as shown in the second trailer for the film, detracts from the deconstruction of the manic pixie dream girl trope that was so important to the novel. In fact, the shift makes Margo into more of a manic pixie dream girl, as she seemingly gets demoted to a plot device for Quentin to learn to let her go and appreciate his friends more.

In this way, the film takes a more male-centered approach to the young adult genre. In his novel, Green set out to tell a story that directly critiqued and debunked what he called the “myth of the manic pixie dream girl.” Green uses the literary young adult genre in order to make an important commentary about a popular trope that could potentially be detrimental to readers in his demographic. The film, however, stays true to the form of the young adult coming of age film. The use of a manic pixie dream girl archetype is extremely common in this genre, and, in excluding the extensive deconstruction of the trope, the film can attract a wider audience. Mainstream film as a medium is typically driven more by financial gain than is literature, and as such, is concerned with getting the largest audience possible into theaters. In producing and marketing the film, executives and filmmakers may have feared that a more deconstructive, feminist take on the manic pixie dream girl would likely alienate audiences who expected a traditional coming-of-age film, especially the male viewers this genre already struggles to earn.

In both the novel and the film, Margo must in some way appear as a manic pixie dream girl. In the novel, she must do so in order for Green to successfully deconstruct the behaviors Margo exhibits. In the film, Margo’s status as a manic pixie dream girl stems from the failure to then deconstruct those behaviors. The manic pixie dream girl, however, does not have to carry such a negative connotation. As Monika Bartyzel argues, the manic pixie dream girl has been co-opted to pigeonhole female characters who defy normal conventions of femininity, while Rabin initially coined the term to “call out cultural sexism and to make it harder for male writers to posit reductive, condescending male fantasies of ideal women as realistic characters.” 10

The imperative moving forward, then, may not be to utilize the trope or deconstruct it, but to make the shift toward less archetypal female characters. We are beginning to see this change take place. Rainbow Rowell’s Fangirl and Eleanor and Park, as well as John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars have all begun to take steps to provide us with stronger, better-written female characters who express agency and exist outside the context of their romantic relationships, while also calling out problematic elements of the manic pixie dream girl as it currently exists. Unfortunately, these texts continue to focus primarily on white, cisgendered, heterosexual femininity. The lack of representation for queer girls and girls of color is disheartening, but we are beginning to see better representation of these intersections in popular media outside the mainstream young adult genre. A continued move in this direction could allow us to see a further shift away from more oppressive tropes into a realm of more progressive, diverse female representation.

Footnotes

- Nathan Rabin, “The Bataan Death March of Whimsy Case File #1: Elizabethtown,” The A.V. Club, January 25, 2007.

- Ibid.

- John Green, Paper Towns (New York: Dutton, 2008).

- Ibid., 14.

- Ibid., 33.

- Ibid., 198.

- Ibid., 284.

- Ibid., 294.

- Ibid., 30.

- Monika Bartzyel, “Girls on Film: Why It’s Time to Retire the Term ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl,’” The Week Magazine, April 26, 2013; Nathan Rabin, “I’m Sorry for Coining the Phrase ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl,’” Salon, July 15, 2014.