Originally presented at the Annual Conference of the Mid-Atlantic Popular & American Culture Association. November 10, 2018, Baltimore, Maryland

Today’s presentation draws on one piece of my larger monograph project entitled The Fairy Tale as Secular Scripture: The Dynamics of Story in Contemporary America. Contemporary for this purpose is roughly defined as my lifetime, from the 1970s to the present. I’ve dedicated my research time over the past eight years to fairy tales because I’m fascinated by the way that we continue to produce and consume them in all forms of media even as we denigrate them for their perceived participation in perpetuating the patriarchy and white supremacy. We read and watch fairy tales with our children in theaters and libraries and we fret over whether we should be reading and watching them in the popular press and parenting magazines. What’s up with that?

The beginning of an answer to that question came from my students in a world literature class at Purdue. The students had read the prologue and part one of Goethe’s Faust. As I was writing notes on the board, I tossed what I thought was a softball question over my shoulder: “What did the prologue to Faust remind you of?” All I got back were crickets. As I kept writing on the board, I sliced the question: “Did the prologue to Faust remind you of anything in the Hebrew Scriptures?” These students had all grown up in Indiana, attending weekly worship services even if they were no longer devout, so I was surprised by the continued silence and the confused faces in the room. I turned to face them and asked, “What about the Book of Job?” Recognition started to dawn.

Goethe wrote Faust counting on his audience to understand his allusion to the Hebrew scriptures. A nuanced understanding of the play depends on an awareness of the difference between Faust’s knowing participation in the dissolution of his own life and Job’s unconsciousness of the reason for his misfortune. We can’t count on twenty-first century students’ ability to make that connection. They are missing a whole layer of the text. And they’re missing it when they read Milton, and when they read Shakespeare, and when they read Elliot and Pound.

You might be thinking that you’d catch allusions. Let’s give it a try.

Can you identify the story that this image references?

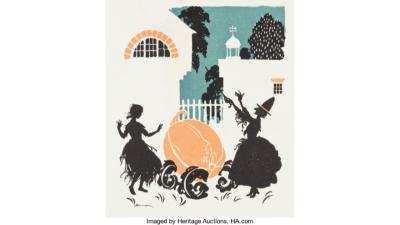

How about this one?

You and my students and pretty much everyone living in the United States can spot allusions to “Cinderella,” to “Beauty and the Beast,” or to “Sleeping Beauty” coming at you from a mile away. And that’s what I want to talk to you about today.

For reasons I discuss in other parts of the monograph and won’t go into today, the motifs and characters of the European fairy tale canon have superseded classical mythology and Judeo-Christian scripture as the building blocks of our texts. Today, I want to show you how this works in two different films that use these building blocks of characters and motifs to create wholly new stories.

Creating new art from pieces is, of course, not a twenty-first century innovation.

In Pastiche: Cultural Memory in Art, Film, Literature, Ingeborg Hoesterey offers a comprehensive overview of the tradition of pastiche from its roots as an early modern Italian “genre of [imitative] painting of questionable quality” to the “rebirth of pastiche in the spirit of postmodernism [that] has taken place across the spectrum of the arts.” Hoesterey defines the genre of postmodern pastiche as dialogic—as the contemporary writers/creators are in conversation with previous works and author—and as self-reflexive—as the pastiche quotes the tradition in such a way as to create complex and layered texts. This second piece, Hoesterey contrasts with what she refers to as the “classic” Hollywood film, which creates a verisimilar presentation of a cohesive reality on the screen. To use a term from the theater world, Hoesterey’s postmodern pastiche breaks the fourth wall.

Hoesterey’s definition of postmodern cinematic pastiche is useful for considering contemporary fairy-tale texts, with one significant adjustment.

Although fairy tale pastiche is always in dialogue with the traditions it draws from, it is only sometimes consciously self-reflexive.

An overt pastiche breaks the fourth wall in one or several ways. It celebrates its allusions to other texts, sometimes in the voices of the characters themselves. It may set its story in hybrid spaces. It presents characters who represent systems of norms and beliefs that are in conflict with one another. Everyone—creator, audience, and characters themselves—is aware that the text is made up of building blocks drawn from other texts.

In contrast, a covert pastiche limits this awareness. The audience may or may not share the creators’ awareness of the pastiche, though it is a richer experience for audience members who do. The characters within the text, however, are completely unaware of their participation in the process of pastiche. Like Hoesterey’s characterization of the “classic” Hollywood film, the covert pastiche presents a coherent setting and the illusion of a single reality. The allusions that delight knowing members of the audience are not noticed by the characters, and the setting is not a hybrid space. When norms are challenged, they are presented as interpersonal conflict among the characters.

These are really egghead definitions of overt and covert pastiche. Let me talk you through a couple of examples.

Disney’s 2012 animated film Brave is an excellent example of a covert pastiche. The film opens with voiceover narration by Merida, the main character, but once the action on screen reaches the narrative present, the film does not break the fourth wall. It presents a single quest narrative within a unified setting that is presented to us, the viewers, as a cohesive whole. This cohesive whole, however, is not an adaptation or a retelling of an existing fairy tale. Rather it is a wholly new tale built from the pieces of existing tales and on the quest-test-transformation structure of the fairy tale.

I’m just going to highlight a few of the building blocks that stand out to me. So here’s the archery contest in which Merida challenges the suitors who wish to win her hand in marriage and bests all comers.

This whole scene is an extended visual allusion to the Disney’s earlier animated Robin Hood film—the organization of the viewing stand, the positions of the characters, and the comical ineptitude of Merida’s suitors. At the beginning of this scene, Merida is in the same position as Maid Marian—in the viewing stand next to her father, but then, she assumes the role of the expert archer and, like Robin Hood, splits an arrow already in the bull’s eye with one of her own.

In addition to the visual allusion, Merida’s choice to “fight for her own hand” is an allusion to the Brynhild character in the Old Norse Fornaldarsögur The Saga of the Volsungs, a valkyrie who has decreed that she will only marry the man who can best her in combat. Indeed, we’ve also seen characters who are resistant to pressure to marry in the Disney oeuvre—Cinderella’s prince, unnamed in the animated film and Kit in the 2015 live-action film, as well as Prince Philip in the animated Sleeping Beauty.

This film uses these, and other (I could fill a whole session!), allusions to build a story that innovates on the basic quest-test-transformation structure of the fairy tale. In this case, the family is not broken by the deaths of the parents or separated by external malevolent forces, but instead by intergenerational disagreement about the norms of the society in which they live. The quest for wholeness then becomes not union with the gendered other to form a new family, but reunion with the generational other to “mend the bond” of the existing family.

There’s so much more to say here, but I’m going to give Brave short shrift in order to talk about another film.

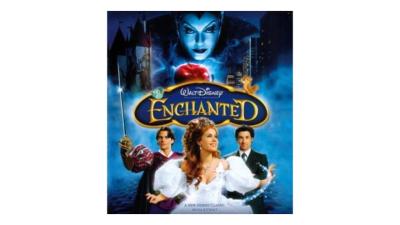

Enchanted is an overt pastiche that revels in its self-referential awareness of bringing together disparate parts. The DVD even includes a track that highlights all of the fairy-tale allusions in the film, and here on the cover we can see some of these elements. We have an apple – “Snow White,” but her dress is not a Snow White dress, it’s a Cinderella dress. Then we have the friendly animals that feature in so many Disney animated films. We see the hybrid setting with castle towers on the left of the image and skyscrapers on the right. We also see the two love interests: Prince Edward looking princely and Robert looking like an urban professional. This film actively draws attention to and enthusiastically celebrates these and many, many other allusions, and it can be enjoyed as a romp through the catalog of fairy-tale tropes and motifs.

To me, though, what this film does so well is criticism. Criticism not only of fairy-tale tropes, but also of the norms of twenty-first century American society. The two-part setting of the film in Andalasia and Manhattan allows the creative team to first establish fairy-tale norms in the former and then challenge them in the latter. These norms include the hero rescuing the love interest, the wicked stepmother, the hero’s ability to communicate with animals, and true love’s duet. In a reversal of the literary convention of urban characters moving into a green world, Enchanted moves characters from an animated natural space into an urban space. Throughout the film, Enchanted’s creative team uses the tensions between fairy tales and contemporary America to criticize both, ultimately moving its main characters toward a compromise that draws on the best aspects of each. Robert helps Giselle learn to think for herself, to look to real women as role models in the book of biographies Robert had given to Morgan, and to see the negative in life as well as the positive. Giselle meanwhile reinfuses Robert’s life with love, dreams, and music. Although Robert does rescue her from the dangers of Manhattan, a city which is familiar to him and unfamiliar to her, and from the poisoned apple, it is Giselle who rescues Robert from the evil Queen, a villain from her native land, and also, arguably, Giselle who rescues Robert from his own cynicism. The Robert depicted in the closing montage of the film, for example, smiles easily, dresses casually, and participates in the games of childhood, none of which the dark-suited, high-powered lawyer of the beginning of the film would have done.

One of the ways this criticism is accomplished is the trebling of fairy-tale tropes in sets that present first a traditional instance in which the trope occurs as expected in Andalasia, a failed occurrence in Manhattan, and an evolved occurrence where Andalasian and Manhattan values have achieved some kind of harmony. In my larger work, I analyze several such trebled sets, but today we’re going to focus on just the falling and catching trope, in which the female love interest is caught by the hero after falling.

This trope is particularly endemic to fairy-tale films because it provides visual evidence of the lead characters’ confirmation to gendered body standards of male muscular strength and female willowy thinness. The first instance of this trope in Enchanted occurs in Andalasia when Giselle is being chased by a troll. She drops from the tree, and Price Edward catches her (6:45-6:50). Giselle falls again in Manhattan, but while Robert breaks her fall, labeling this “catching” would be generous (19:05-19:10). The third time, it is Giselle who catches Robert as he falls from the Empire State Building (1:35:05). The connections among these moments in the film are made clear first by the director’s choice to make the visual presentation of the character in danger the same all three times: she or he is hanging from a cylindrical object with only the fingers bearing the body’s weight. In all three scenes, the camera zooms in specifically on the hands (06:42, 19:05, 01:35:01). Then, in the third presentation of this trope, the film makes a self-referential comment on its evolution in the voice of the evil queen, “Oh, my. This is a twist on our story. It’s the brave little princess coming to the rescue. I guess that makes you [Robert] the damsel in distress, huh, handsome?” (1:32:49). Thus, it is clear that the trebling and evolution of tropes were deliberate choices on the part the creative team responsible for Enchanted.

This analysis of the fairy tale pastiche shows that the fairy tale is a generative genre, which allows authors and film studio creative teams use the dramatis personae and motifs of the fairy tale canon to build new narratives. These new, self-critical versions of fairy tales have the potential to become canonical themselves. Unlike sacred scripture, which tends to form closed canons that resist further additions once codified, the secular scripture of the fairy-tale canon continues to be open to the inclusion of newer adaptations, sometimes even preferring newer versions to older ones, as with the dynamic by which contemporary Americans tend to be more familiar with the animated fairy-tale films than with the Grimm’s versions in Kinder- und Hausmärchen. Indeed, if the fairy tale is our secular scripture, the cinema screen is our stained glass window, the medium that allows us to tell our important stories in pictures for audiences to view en masse.

Although they engage in the process of creating fairy tale pastiche very differently, the films Enchanted and Brave each offer excellent examples of this contemporary genre. The ways that these two films interact with the canon confirms the pervasive presence of fairy tales in contemporary American culture. Enchanted is able to draw on a variety of fairy tales for humor and commentary because the creative team could depend on the audience’s knowledge of the stories to which they were making allusions. Brave is able to tell a new story that can fit into the canon seamlessly because its creative team made use of the building blocks of that canon. Each of these films engages with the canon in order to place discourse and commentary in the space between the audience’s knowledge about fairy tales and these new pastiche fairy tales. It is by virtue of the fact that the fairy tales of the canon have become contemporary America’s secular scripture that the creative teams behind Brave and Enchanted could accomplish these goals in this way.

Bibliography

Andrews, Mark, Brenda Chapman, and Steve Purcell, dirs. Brave. 2012; Emeryville, CA: Pixar Animation Studios. Film.

Branagh, Kenneth, dir. Cinderella. 2015; Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures. Film.

Clyde Geronimi, Clyde, Wilfred Jackson, and Hamilton Luske, dirs. Cinderella. 1950; Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures. Film.

Geronimi, Clyde, dir. Sleeping Beauty. 1959; Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures. Film.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Faust in Norton Anthology of World Literature, Shorter Second Edition, Vol. 2. John Bierhost, Ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, pp. 314-420.

Hoesterey, Ingeborg. Pastiche: Cultural Memory in Art, Film, Literature. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Lima, Kevin, dir. Enchanted. 2007; Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures. Film.

Reitherman, Wolfgang, dir. Robin Hood. 1973; Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Pictures. Film.

The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. Trans. Jesse L. Byock. New York: Penguin, 1990.

Image Credits

Baumgartner, Jack. Jacob Wrestles with God. 2011. The School of the Transfer of Energy, https://theschoolofthetransferofenergy.com/tag/jacob-wrestling-angel/

Rackham, Arthur, illustrator. Cinderella. Charles Seddon Evans, author. London: William Heinemann, 1919, frontispiece.