Otherworld, a permanent, interactive, large-scale, mixed-reality installation art exhibit, opened on August 4th, 2023 in northeast Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1 It is the second such Otherworld exhibit, the first being located in Columbus, Ohio. The exhibit’s website describes Otherworld as “a new kind of art + entertainment experience that combines elements of community, art, and self-expression with those of immersive theater, escape rooms, children’s museums, and haunted houses.” 2 And, indeed, Otherworld dazzles with both its art and its entertainment. The various exhibits are full of color and sound along with interactive elements that enhance the visitor experience. However, Otherworld does not make good on providing visitors with a fully immersive experience; not all spaces are fully realized and there are some simple enhancements Otherworld could make to aid in world-building. Moreover, a hinted-at thematic connection for all of the spaces in the exhibit is never fully fleshed out, leaving visitors unsure of the possible meaning(s), or if there even is a meaning, of some of the elements they experience.

Otherworld consists of over fifty unique rooms, created by one hundred artists and craftspeople, and covers 40,000 square feet. 3 Each room features its own subject matter but most share an overarching theme drawn from the exhibit name itself, with alien landscapes and strange looking beings (either larger or smaller than human scale), created from a collection of materials including textiles, wallpaper, concrete, fiberglass, foam rubber, industrial elements, delicate appliques, and running water (sometimes all at once), augmented by LED tube lights, fiber optic lights, and mapped projection. Entry is based on timed tickets, which helps with crowd control and allows visitors to have the space and opportunity to interact with all of the elements of the exhibit.

A quiet hum is played via hidden speakers in some rooms, though a few rooms have their own music, notably a Victorian gothic horror-style room with ominous organ music, and a room featuring three giant feminine figures wearing silver robes, one holding a glowing orb, with stripped down electronic music playing. Lighting gives off an eerie glowing spaceship-type feel that is very effective in helping to set the mood and in creating a strong sense of alterity.

There are no docents, signage with room number or title, gallery maps, audio tours, or prescribed order for moving through rooms (or for interacting with them), which visitors have come to expect when viewing traditional art exhibits. 4 Because all rooms have at least two doorways, sometimes covered by heavy curtains, a visitor might miss one or more. But even if someone backtracks to an already viewed room, new elements pop out that may have been missed the first time. This lack of guidance/stated curatorial intent accomplishes two key things: it helps visitors find things on their own, and at their own pace, without any sense that there is a “right” or “wrong” way to view the exhibit, and it allows visitors to discover on their own what various levers or buttons do.

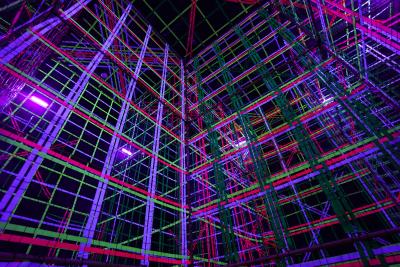

The interactivity level of the rooms varies. Some rooms do not feature interactive elements, though everything can be touched and lighting may change. Other rooms contain objects which can be leaned against, or sat on/in, like small cubbies and freeform furniture like beanbag-type chairs, as well as swinging pods that hang from the ceiling. Visitors may even be caught in a rainstorm. In one room, pulling levers projects what looks like different textures on a giant and adorably plump fiberglass “stuffed animal”-type creature with horns. In another, visitors can try on a collection of masks in front of mirrors. In another room, full of dozens of long corrugated pipes running up and down and covering huge swaths of the walls, manipulating levers on a computer touch screen changes the color of various tubes from red, to green, to blue, depending on the user’s choices. In the previously mentioned room with the massive figures in iridescent gossamer robes and dramatic lighting, visitors can manipulate six touch screens that increase or decrease the decibel level of isolated tracks of stripped down electronic sounds to play a kind of techno music reminiscent of a dance club. It’s a space where spontaneous dance parties might break out. These manipulatable experiences allow visitors to interact with one another, as well, as sometimes the effects of moving dials and levers only becomes clear when visitors watch one another or work together.

Simply put, the art at Otherworld is phenomenal; the creatives have designed and constructed spaces that are magical. The exhibit is a feast not just for the eyes, but for several other senses as well. The sights, sounds, materials, and lighting chosen by the artists combine to create what does, indeed, look and feel like another world or collection of worlds. The technical artisanship is of very high quality, as are the materials used. More specifically, the artists’ world-building in almost every single room is stellar, immersing visitors in each and every space fully. The space contains a large water feature—a weeping willow tree that actually “weeps,” with branches made of color-changing LED tube lights, and several elevated walkways under it and “rain” that falls from the ceiling into a small reflecting pond that surrounds the base of the tree. Incredibly, the branches of the tree, along with a “forest” of simulated bamboo that surrounds it, are made of two miles of LED lights. 5 The lighting and audio are synched to the “rain” as it falls, and visitors can stand under large branches in the center to avoid getting wet. The effect is one of being inserted into James Cameron’s film Avatar (2009).

Photo courtesy of Otherworld Philadelphia

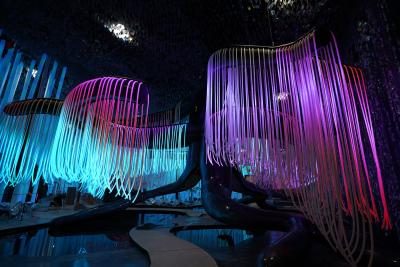

A standout here, again, is the room with the massive feminine figures and electronic music; it’s a perfect example of taking theming all the way up the walls to a vaulted and coffered ceiling of which each panel changes color, as if a disco’s illuminated floor has been flipped to the top of the room. Otherworld shows the visitor what the successful marriage of art and entertainment in an interactive, immersive, installation art exhibit can achieve.

Photo courtesy of the author

But there are some missed opportunities as well. Otherworld, with its multi-sensory approach to art and visitor immersion, would benefit from considering the addition of scent to aid in world-building. Research on combining scent with cultural heritage experiences tells us that curated smells “can positively impact visitor engagement and active exploration of an exhibit.” 6 The gothic horror-style room previously mentioned features a score of illuminated hanging candelabras but, for safety reasons, no actual lit candles. Adding the scent of wax or smoke from a just-snuffed wick would enhance the story the room is trying to tell. In a small, cozy room with a jungle theme (albeit a jungle full of eyeballs and a gargantuan caterpillar mixed in with dirt and foliage), an earthy or woodsy smell could further immerse the visitor in the space.

Photo courtesy of the author

Photo courtesy of Otherworld Philadelphia

And while the lack of prescriptive signage or cues is a plus for the exhibit as a whole, there are some rooms in which the intent of the artist is not clear and visitors are unsure how to interact with the art, or even if they can. Some elements would benefit from being more fully fleshed out. For example, in one room with large tree trunks with humanoid hands extending from them, the natural instinct is to touch the hands—but nothing happens, there are no interactive elements. In another artist’s hands, the tree trunk or hands might emit sound, or some other phenomena, when touched. In another very large space containing several exhibits within it, the art extends to the walls only; the ceiling is untouched and looks like an average warehouse ceiling. This lack of decoration breaks the fourth wall for visitors and hinders full immersion.

Photo courtesy of Otherworld Philadelphia

A striking example of how an interactive space could be made more clear is a room that allows two players to play an Asteroids-type game using joysticks. The light displays of asteroids being destroyed play out on all four walls surrounding the players, as well as on the ceiling and floor. The effect of being immersed inside of a video game is both novel and dazzling. But it’s unclear what the joysticks actually do, and how to use them, as the standard “aim and fire” approach doesn’t seem to have the expected effect. Players can’t tell if they don’t understand how to play the game, whether the joysticks are broken, or whether the asteroids exploding when hit are pre-programmed and the game is not actually interactive at all. This flawed interactivity was disappointing; when playing a competitive game, even in a world of virtual reality, it seems visitors still want some level of actual reality.

Finally, and most significantly, Otherworld Philadelphia lacks any semblance of a cogent theme beyond a “surreal landscape of science fiction and fantasy.” 7 This would not be a problem per se, as art for art’s sake always has value, but for one room in the exhibit. This room is set up like a handsome office with a desk and bookcases of dark wood, an office chair, and a computer mouse that visitors can use to pull up documents and email exchanges on a monitor. Some of the documents appear to be Rorschach-like ink blots. The email messages are replies to messages from individual, named, explorers of these other worlds (a mention is made about one explorer being lost in the room with masks and mirrors) who have seemingly contacted ATAM (a home base/command central of sorts), the director of which presumably occupies this office. But the email exchanges lack a beginning or end, so the reader only gets confusing bits of information that do not aid the goal of solving any riddle that might exist.

Otherworld does not need to have a concerted theme, certainly, or answer every question it raises, but the inclusion of the office room reads as a rather clumsy afterthought, an attempt to create an origin story for the entire exhibit and unify the disparate collection of rooms. But the information found in this room hardly constitutes a deep narrative; it is a suggestion, a whisper, of one way to understand these spaces and the connections (or lack thereof) among them. That this room comes near the end of the exhibit is more confusing still. The email exchanges readable in the office room hint at a possible backstory for Otherworld Philadelphia; a backstory that is never fully fleshed out by the rooms that come before or after it.

Some of the rooms do contain small wheat paste fliers. Some are written in an alien language, and others seem unrelated to the rooms in which they are placed. There are various possible interpretations of the meaning of these, from a chemical spill and cover up, to a political campaign, 8 to an unethical corporation carrying out tests on alien subjects. 9 But if these signs, small and often placed in dark rooms, are meant to represent an overarching narrative, they are not up to the task. Representing a theme, or creating riddles for visitors to solve, would be better accomplished by more sophisticated semiotic means—visual (or even audio) cues in design and the objects chosen by the artists. If the disparate rooms have a specific story, or stories, to tell, the objects and motifs in them should be able to be decoded more easily. If Otherworld does indeed have a puzzle to solve, then using only clues found on cryptic fliers scattered through some of the rooms, or extremely subtle hints included in the decor, does not serve the exhibit’s narrative and interactive aims.

Both Otherworld locations are the brainchild of founder and CEO Jordan Renda, who created the overall concept and then hired artists to design individual rooms, as opposed to a model like the very artist-forward Meow Wolf House of Eternal Return exhibit in Santa Fe, New Mexico, that was created by a starving-artist collective working together for years to tell different aspects of a cohesive story through the art each member makes. 10 The collaboration that happened among Meow Wolf artists, long before House of Eternal Return was a fully-realized exhibit, certainly positively influenced its direction and cohesion. Renda’s approach was to create both Otherworld locations using a “top-down framework . . . as far as establishing high-level themes, an overarching, loose narrative, and parameters to work with . . . It may start with a pretty rough idea.” 11 This top-down approach to creating a realizable narrative, which many artists are then tasked with independently conveying, does affect the experience visitors have as they move room to room and try to understand the spaces as a whole.

It is interesting that Otherworld Philadelphia provides no origin story for visitors, because the original Otheworld in Ohio does. The website for the Ohio locations reads:

You have volunteered as a beta tester at Otherworld Industries, a pioneering tech company specializing in alternate realm tourism. But upon arrival at the desolate research facility, you’re left on your own . . . Exploring restricted laboratories inevitably leads you to discover a gateway to bioluminescent dreamscapes featuring alien flora, primordial creatures, and expanses of abstract light and geometry . . . 12

Photos of different rooms scroll past online, including one of an antiseptic “mission control” space with a long U-shaped table full of nothing but unattended computer stations and large letters spelling “Otherworld Industries” above them. Between the expectation set via the website, and walking through this room that looks clinical and scientific, and others that are fantastical, visitors already have a sense of the sort of journey Otherworld Columbus may take them on, and perhaps even a sense that there will be clues to decode. Moreover, the Ohio Otherworld website lists, by name and role, over twenty artists who worked on the space and includes photos of them and/or their work. None of the artists of the Philadelphia location are listed, either at the exhibit, or online, which is certainly a misstep and one that should be rectified.

Otherworld Philadelphia ticks all of the boxes laid out by cultural anthropologist Scott A. Lukas in his discussion of the complementary modes through which theming and immersion operate: (1) architecture (thematic architectural forms, often related to place, brand, or other context), (2) material culture and design (décor, interior design, and other sensory forms that offer an evocative potential), (3) narrative (text or backstory that expresses the purposes or meanings of the space), (4) technology (various technological forms that increase the thematic and immersive potentials of the space), (5) performance (forms of acting and aesthetics that enhance the design, architecture, and material elements of a space 13 ), and (6) guest role/drive (the interpretations, desires, and feedback of guests as they respond to a themed or immersive space). 14 Unlike traditional exhibits that may afford the viewer the opportunity to “go back in time,” visitors here have the opportunity to “go forward in time,” or even lose a sense of temporality altogether. Ultimately, despite some shortcomings, Otherworld Philadelphia successfully delivers on its twin promises of art and entertainment.

Footnotes

For more information, see https://otherworldphila.com/, accessed September 1, 2023.

https://help.otherworldphila.com/hc/en-us/articles/14022732354843-What-is-Otherworld-Philadelphia- , accessed sept 4, 2023.

Conversation with General Manager Chris Fitzpatrick on September 21, 2023

A small number of artists have minute listings, such as QR codes, fairly well hidden among their work.

Email correspondence with General Manager Christ Fitzpatrick on September 27, 2023.

Caro Verbeek, Inger Leemans and Bernardo Fleming, “How Can Scents Enhance the Impact of Guided Museum Tours? Towards an Impact Approach for Olfactory Museology, The Senses and Society 17:3 (2022), 315-342, DOI: 10.1080/17458927.2022.2142012, accessed on September 3, 2023.

https://otherworldphila.com/ accessed September 4 2023.

https://www.phillymag.com/things-to-do/otherworld-interactive-experience/ accessed on September 1, 2023.

https://www.visitphilly.com/things-to-do/attractions/otherworld-philadelphia/ accessed on September 8, 2023.

https://meowwolf.com/about accessed on September 1, 2023.

https://blooloop.com/theme-park/in-depth/otherworld-art-meets-tech/ accessed on September 8, 20023.

https://www.otherworld.com/main/about accessed September 1, 2023.

Here, I am interpreting acting as interacting with the elements in the room as well as watching other visitors, many of whom have a costume-y aesthetic.

Scott A. Lukas, “Introduction” in A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces, ed. Scott A. Lukas (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon/ETC Press, 2016), 5.

References

Lukas, Scot A. “Introduction” in A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces, ed. Scott A. Lukas. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon/ETC Press, 2016.

Verbeek, Caro, Inger Leemans, and Bernardo Fleming. “How Can Scents Enhance the Impact of Guided Museum Tours? Towards an Impact Approach for Olfactory Museology.” The Senses and Society 17:3 (2022), 315-342. DOI: 10.1080/17458927.2022.2142012