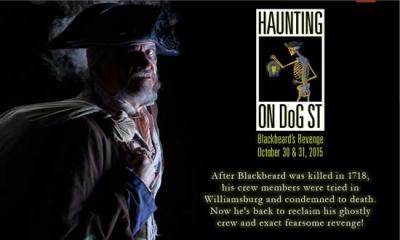

In early September 2015, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in Williamsburg, Virginia announced its brand new Halloween program, “Haunting on DoG Street: Blackbeard’s Revenge,” scheduled for October 30 and 31st. In addition to free trick-or-treating down the main streets of Colonial Williamsburg, or CW, adult visitors could purchase 10-15 dollar tickets (children were 5 dollars) for two immersive events: “A Pirate’s Life for Me” (kid-friendly) and “Under Blackbeard’s Flag” (decidedly not kid-friendly, and including a zombie walk). As you might imagine, reactions were mixed. One blog criticized the programming as evidence of CW’s “spiraling out of the field of historic sites, and into a new, self-defined realm of history-themed leisure destinations.” 1 The entire programming felt way too gimmicky for CW super-fans.

The criticism reached such a crescendo that it required written damage control from Colonial Willamsburg’s recently installed CEO, Mitchell Reiss. In an October 16, 2015 essay to the Virginia Gazette newspaper, Reiss pointed out the lucrative nature of Halloween-themed programming (he mentioned a Washington Post statistic that American’s spent 7.4 billion dollars on Halloween last year), while carefully pointing out that visiting CW’s Historic Area is not “just [an] educational [experience], but [a] personal one.” Reiss closed his essay with the following statement:

While most other venues will revert to business-as-usual on Nov. 1, the tale of Blackbeard and his crew will live on here, as one of the many narratives that our actor/interpreters weave from the pages of history. Every day, these individuals find new ways to draw people into the story of early America. And in doing so, make the experience all the more relevant, and all the more real. 2

I quote this statement at length not because I find Reiss’ plea particularly heartfelt, but because it fails to explicitly mention the economic issues plaguing all museums, and historic house museums (or HHMs) in particular. And while Reiss is correct in calling CW’s new programming “visitor-centered,” he also pairs the personalized experience of heritage tourism with a renewed commitment to historical authenticity – whether legitimate or not. And perhaps his persuasive essay was unnecessary, because in spite of very vocal criticism, both events sold out. 3 Someone was buying these pricey tickets.

Colonial Willamsburg is only following in the deep footsteps of its peer Tidewater institutions – in fact, it’s a bit late to the whole “haunted houses” game. Bacon’s Castle, in Surry, Virginia, touted to be “built in 1665, [and] the oldest brick dwelling in the United States,” hosts an October event with the Center for Paranormal Research and Investigation (CPRI); for 30 dollars, guests over the age of twelve explore the low-lighted building with paranormal investigative tools. 4 On a 36 dollars progressive tour of three James River Plantation houses, Berkeley, Edgewood and Shirley, guests receive “an insight of the spirits and mysteries of these three historic homes in Charles City, Virginia.” 5 And the Tidewater HHMs are in good company. Across the country, many hallowed historic houses use ghost tourism to drum up funds and attendance: • On October 30, from 3:30-6:30 pm Mount Vernon, in Alexandria, VA, hosts “Trick-or-Treating at Mt. Vernon” with costume contests and fall crafts. There are prizes for the best Martha and George Washington kid costumes. In 2015, this event costs 10 dollars for adults and 5 dollars for children. • The House of Seven Gables in Salem, MA hosts two different performances; “Legacy of the Hanging Judge” and “Spirits of the Gables.” These evening experiences move visitors in a narrative through the house space. In 2015, these events were 15 dollars apiece. • The National Building Museum in Washington, DC offers non-members over the age of ten a 25 dollar ghost tour (members pay 22 dollars), complete with “found” video footage, available online, purporting to show the disappearance of the museum’s “chief preparator.” It’s all very elaborate.

The aforementioned examples are engaging in ghost tourism, which Michele Hanks defines as “any form of leisure or travel that involves encounters with or the pursuit of the ghostly or haunted.” 6 I’d also add that while these tours tell stories about the past, they are also a conscious encounter with a geographically and socially specific present. I agree with Hanks’ assessment that ghost tourism is a form of “disembodied heritage” tourism where absences and incomplete narratives unsettle the visitor, who has deliberately chosen to take part in such an experience. Ghost tourists are seeking the spooky and the spectral – however tongue in cheek. This is an area of scholarship well trodden and critiqued by historians, such as Tiya Miles and Erik Seeman, as well as geographer Glenn Gentry and anthropologist Hanks. 7 The majority of these texts on ghosts and spectrality emphasize absence, rather than presence, especially when dealing with marginalized or subaltern identities. When coupled with the material and economic forces of tourism, these identities are often further marginalized and exploited, and scholars are understandably wary of ghost tourism’s utility.

Here, I must consider one (of many) critical questions: when does the historic house stop being a museum and start becoming an entertainment venue? Is the distinction ever completely clear? Busch Gardens, an amusement park situated a few miles from Colonial Williamsburg, annually hosts its “Howl-o-Scream,” replete with haunted houses and an extended, manufactured narrative about how “an excavation crew uncovered a centuries-old house buried deep beneath the ground.”[^8] (I like to think this is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the region’s plethora of historic houses.) The scholarly criticism of ghost tourism focuses on how ghost-centric “events” at HHMs handle (or mishandle) history. I am interested less in the illusion of “authentic” historical experiences, and more in how certain forms of ghost tourism might be a useful (and lucrative) interpretative technique to illuminate “sites of historical horror” and get visitors personally invested in HHMs. 9 I want to suggest that the profitable ghost tour can be a productive way for tourists to experience the past – but only if led by capable, sensitive guides. Thoughtful mediation is necessary.

It is worth considering the spectral, manufactured town of Williamsburg, Virginia. For visitors, it is often hard to distinguish between the actual town and its eponymous living history museum. The conceptual architect for Colonial Williamsburg’s restoration, the Reverend Mr. W.A.R. Goodwin, was “sensitive … to the ghosts of the American Revolution in Williamsburg [and] he wanted to turn the town into a national shrine.” 10 However, revolutionaries aren’t the only ghosts; the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are also mapped simultaneously on the cultural landscape as a palimpsest of identities and experiences. Despite recent institutional re-workings of public identity and memory, scholars observe that CW (and, by extension, some of its peer institutions) encouraged its visitors to maintain a dangerous narrative of patriotic nostalgia. 11 I wonder if ghost tourism – at a lesser-known HHM in Williamsburg - can combat and perhaps revise this familiar narrative about an often-misunderstood place.

The Manor House at Powhatan Plantation is a notable example of a historic house museum. Renovated and refurbished in 2009, the Manor House sits at the center of a gated timeshare community. Unlike the larger Colonial Willamsburg historic houses museum, the Manor House interprets its genealogy as ahistorical, a method used by many museums with little space or budget for specific periodization. Time collapses at this historic house museum, as the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, and even twentieth centuries are depicted concurrently in décor, architecture and ghost stories. This collapsing, however problematic for scholars, allows the Manor House to successfully accommodate the historical and recreational interests of visitor and management alike; it also separates it from CW’s eighteenth century obsession. Like its aforementioned counterparts, the privately owned and funded Manor House offers ghost tours; through historically-centered visitor experiences 12 that use second-hand interpretation, the museum engages the visitor more with the assistance of capable guides. 13

Second-hand interpretation, as defined by theater historian Scott Magelssen, allows the visitor to have a “hands on experience… with [personal] agency in determining the trajectory of their encounter with history.” 14 Using this “hands on” method, visitors to historic homes can potentially see all the histories present at a site: the enslaved, the gendered, and the socially peripheral. Second-person interpretation eschews the familiar third-person interpretation, which often narrates privileged lives from historically distant spaces: think “George Washington lived here.” Second-person also differs from performed first-person interpretation, where an actor acts as the historically privileged person: again, think “I am George Washington.” In first and third-person interpretation, the visitor learns only “what has been chosen by the institution as worthy of remembrance.” 15 So, in other words, first and third-person interpretation renders the visitor a passive spectator subjected to a historical lecture; second-person interpretation requires the visitor’s interaction. Often using the realm of social and cultural history, second-person interpretation calls for authoritative, engaged involvement with history. This allows the visitor to vocalize or perform his or her feelings, questions, and historical knowledge (however scant or inaccurate). It also requires work; second-person interpreters must leave their modern awareness behind, however momentarily, in order to perform a specific account. This could create problems for those less-than-historically aware visitors, lacking the scripted empathy ideally displayed in first and third interpretative modes. However, the ghost tour allows for inclusion without losing modern day tethers. 16 Traditionally, historic houses have highlighted elite, white households. 17 However, with the implementation of new interpretative techniques, house museums can also tell the story of marginalized persons. These tellings are potentially problematic, for they operate in the contrived space of ghost stories; still, the stories get told. Uniting the visitor, the archive, and the folkloric, the historic house provides an ideal environment for second-person interpretation by presenting object-driven rituals for the visitor to perform firsthand.

Drawing on one tour offered at the Manor House, the 10 dollar “Ghost Academy and Tour” offered on Friday and Saturday evening, I dare to suggest this interpretative technique for HHMs. The tour starts with a disclaimer: visitors may or may not have “paranormal” experiences. However, the average visitor is usually open to the possibility of paranormality and historical edification. 18 The ghost tours I attended were composed of engaged adults; they did not scoff or challenge the tour guide. We were introduced to the Virginia Paranormal Occurrence Research project, of which our guide was a founding member. Authenticity – I know, a messy term – was established for the visitor. The ghost tour attendees were immediately made informal members of the project by being handed the following paranormal research tools: voice recorder, dousing rods, flashlights, and digital voice recorder. My fellow participants treated these items with care; if there was initial silliness, it disappeared once the tools were passed out.

The ghost tour began with a storytelling session. There was an obvious historical focus, and ethical ghost hunting was stressed; scare tactics were limited, though we were plunged into suggestive darkness on two occasions. Our group learned about three types of ghosts: residual, non-human, and intelligent. The latter type populated our ghost tour; these specters interacted with the living in palpable ways. We were then introduced to five specific ghosts: Richard Taliaferro (Tolliver), renowned eighteenth-century architect, landowner, and slaveholder; Eliza Taliaferro (Tolliver), his dutiful eighteenth-century wife; John Smith, the enterprising Jamestown colonist of 1607; Prisoner Tommy, the incarcerated inmate of the basement dungeon; and Gus, a flirtatious enslaved man. Once we knew about these ghosts, the third person interpretation was complete. We were sent on our way to interact with the ghosts, with their spectral status often reinforcing normative historicized behaviors. The ghosts all operated in the same temporal moment for the visitor: now. But the ghosts were not completely static, as they were also products of specific historical periods. Each represented a particular moment for the house; thus, the palimpsest of Williamsburg was revealed for the visitor.

After learning the ghost stories, the ghost tour participants were set free to roam the house with the previously mentioned paranormal research tools. I tried to observe, making note of the participatory pleasure felt by the ghost tour participants, surprised by my own trepidation. We wandered the house looking for specters that haunt the present. Visitor participants asked questions of Gus: “Why do you chose to haunt where you were enslaved?” and “Why are you so happy here?” They interrogated Richard Taliaferro: “Do you miss your library?” and “Do the visitors bother you?” Eliza did not escape inquisition: “Was it hard to be married to Richard? Was he difficult to live with, as he grew increasingly reclusive?” Prisoner Tommy, who dwells in the off-limits basement, is asked, “What happened to you?”

The visitors engaged in not only the formation of questions but also hypothetical answers, which they offer to one another based on what they know of each historical personage. In compiling questions to ask the darkened house, the visitors engaged in their own performances, using historical effigies to create conversations (however imagined) with historically distant personalities. Effigy, to borrow Joseph Roach’s terminology, refers to that which “fills by means of surrogation [or cultural reproduction] a vacancy created by the absence of the original”; 19 the living visitors played off the ghostly characters and recreated absent historical personae. In this manner, the participants interacted with semi-stock characters that encouraged new thoughts about the past from the present; the tourists paired their memories with new knowledge from the ghost tour, and this created conversations to be had with the guide and the specters haunting the house. We were asked to learn and think differently. We were also roaming beyond the normal, daytime tour space, experiencing the house in an excitingly tactile manner. I can’t remember another tour where I could feel the structure so easily.

This approach, while innovative and imaginative, is not without its problems. With each ghostly “interaction,” the visitor creates a new narrative that may or may not be historically accurate. In fact, some of the ghost stories shared concerned composite characters that reinforce dangerous, racialized stereotypes. In an example, Gus, the enslaved man, is depicted as overtly flirtatious; during the tours, he was accused of playfully pinching female backsides and blowing in female’s ears. This behavior, however laughed off, perpetuates myths about hypersexual men of color who prey on white women. It was difficult to hear my fellow ghost tour participants jokingly ask Gus to “hit on his favorite” female. While the guide encouraged respectful ghost hunting, the participants were occasionally insincere. They were not making fun of the ghosts, but they were not revering them either; perhaps this flippancy was a way to combat their fear. However, according to Magelssen, “Making so-called errors … can actually be much more productive to discourse than blindly following the historical script.” 20 In the hands of a prepared second-hand interpretative guide, the Gus moment could be explored and interrogated; in this way, multiple histories could be revealed instead of the familiar narratives.

In conclusion, attendance to historic house museums has declined since the 1970s; 21 museums in general have suffered in terms of visitorship and funding. 22 It is easy to see the connection between lowered attendance and financial difficulty, but how can these institutions re-gain the interest of the visiting public? While it can be difficult to pinpoint exact reasons for a decline in visitors, history museums in general now strive to create “interactive and engaging” 23 experiences for twenty-first century audiences. 24 And, perhaps most interestingly, such sensory-laden engagement and immersive interaction helps the visitor/learner feel integral and important to the production of history. 25 Historic sites experience attendance surges when they implement participatory visitor experiences. 26 Despite the potential for inaccuracies and inappropriateness, the Manor House ghost tour offers one possible solution for the economic and cultural woes of historic house museum. This method encourages constructivist engagement and interaction, and includes the visitor in the narrative as much as possible. Such inclusion might allow for critical analysis of thorny historical issues that still haunt our society. If carefully deployed, the second-person interpretative ghost tour model might provide institutions with revenue potential while engaging and educating twenty-first century visitors. 27

Footnotes

- Taylor Stoermer’s Oct. 20, 2015 entry on The History Doctor blog: http://taylorstoermer.com/. Critics also posted to Facebook: “[K]eep CW period correct and educational” and “Is it too much trouble to actually type the words ‘Duke of Gloucester’?”

- Mitchell Reiss, “Essay: Halloween gets historical due,” The Virginia Gazette, Oct. 20, 2015.

- “A Pirate’s Life for Me” sold out in early October, and “Under Blackbeard’s Flag” exhausted its ticket supply by the week of October 26.

- “Haunted Event with CPRI,” http://preservationvirginia.org/events/detail/haunted-event-with-cpri3.

- “Haunting Tales and Tours,” http://www.berkeleyplantation.com/calendar.html

- Michele Hanks, Haunted Heritage: The Cultural Politics of Ghost Tourism, Populism, and the Past (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2015), 13.

- Few monograph length books exist, with the exception of Hanks (2015). Spectrality studies has a much more prolific scholarship. Following Jacques Derrida’s call for a “spectral turn” in analysis, scholars from sociology to literary studies sought the absences rather than the presences in a myriad of texts (Avery Gordon’s Ghostly Matters; Judith Richardson’s Possessions; Kathleen Brogan’s Cultural Hauntings; Owen Davies The Haunted: A Social History of Ghosts). Spectrality even merited its own anthology, The Spectralities Reader, edited by Maria del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren.

- Teresa Goddu, Gothic America: Narrative, History and Nation, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 3.

- Richard Handler and Eric Gable, The New History in an Old Museum, (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), 31.

- Anthropologists Richard Handler and Eric Gable observed this phenomenon in Colonial Williamsburg during the mid-1990s.

- Carson, “The End of History Museums,” 17-20.

- Scott Magelssen, “Making History in the Second Person: Post-touristic Considerations for Living Historical Interpretation.” Theatre Journal 58.2 (2006): 298.

- Magelssen, “Making History,” 291.

- Magelssen, “Making History,” 293.

- See Laura Peers on Native American interpreters at five living history sites in her article, “‘Playing Ourselves’: First Nations and Native American Interpreters at Living History Sites,” Public Historian (Autumn 1999).

- Sherry Butcher-Younghans, Historic House Museums: A Practical Handbook for Their Care, Preservation, and Management, (New York: Oxford UP, 1993), 5.

- Jessica Foy Donnelly, “Introduction,” Interpreting Historic House Museums, (New York: Altamira Press, 2002), 9.

- Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance, (New York: Columbia UP, 1998), 36.

- Magelssen, “Making History,” 305.

- According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, there are 15,000 across the U.S.

- Cary Carson, “The End of History Museums: What’s Plan B?”, The Public Historian 30.4 (Fall 2008): 15-16.

- Carson, “The End of History Museums,” 17.

- In the Center for the Future of Museums’ TrendsWatch 2014, a publication put forth from the Alliance of American Museums, the inclusion of multisensory experiences, or synesthesia, in museum spaces was an element in successful museum programming. TrendsWatch 2015 calls for renewed commitment to personalized visitor experiences, noting: “This trend is playing out in three arenas: the creation of personalized goods, the filtering of personalized content and the creation of personalized experiences.”

- Carson, “The End of History Museums,” 20.

- Carson, “The End of History Museums,” 13, 18.

- Some new publications (all from Left Coast Press) also deal with this topic: October 2015’s Anarchist’s Guide to HHM by Frank Vagnone and Deborah Ryan; and 2011’s Letting Go: Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World edited by Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene and Laura Koloski; 2008’s The Power of Touch: Handling Object in Museum and Heritage Contexts by Elizabeth Pye.