It was revealed in the New York Times and on national television in the summer of 2015 that Africana Studies professor and N.A.A.C.P. director of the Spokane chapter, Rachel Dolezal, had possibly falsified her ethnicity. She was subjected to national scrutiny and ridicule after it appeared she fabricated her own racial background. The Times also wondered if Rachel Dolezal would give up her “part-time teaching position in African American Studies at Eastern Washington University.” She did. It is fascinating to me that this little story garnered so much national attention. What ensued was a Swiftian tempest in a teapot in which pundits labeled Dolezal a “liar.” She was living as a black woman while her parents outed her as white. They even went on national television to show Rachel Dolezal’s baby pictures. The combination of white parents and a white little girl added up to one conclusion—that Dolezal was indeed white. It felt like everyone I knew that summer was angry at Dolezal. 1 She seemed to be a white woman “passing” as an African American. Historically, passing was usually performed by African Americans light-skinned enough, often of mixed racial background, to “pass” as white. There are dozens of books on the topic by sociologists, psychologists, and historians. Passing is anything but new, as this paper will discuss. Passing, as a sociological phenomenon, is generally studied in terms of race, class, gender, sexual orientation and/or (dis)ability. Add the 21st century concern for our personal image (think Facebook) and the issue gets even muddier. We see reflected in television and film, Youtube, the blogosphere and the Twitterverse discussions of passing, although we may not immediately recognize it as such. This is no doubt a reflection of our American obsession with race, which has again hit the media (and our hearts) this summer of 2016. This paper will explore many facets of passing as the term is used in 2016 and demonstrate that passing is merely a part of one’s identity formation; it is not a crime.

One quick example is in season one of American Horror Story’s “Murder House” when several characters pretend to be something they are not. Ben pretends to be the devoted, faithful husband even though he impregnated his girlfriend after he told his wife it was over. Ben is passing as a faithful husband. Addie, the young woman with Down Syndrome, wants to be a “pretty girl” for Halloween and dons a mask her mother provides for her. The mask or masking is an old school literary trope for passing. Think Romeo and Juliet at the masquerade, pretending they are not from rival families. Think Nora at her masquerade ball in A Doll’s House, pretending to be the happy housewife while her husband infantilizes her. Think the Lone Ranger. And legions of superheroes. Think politics and sports. Note that a mask is not a requirement in passing, but merely a trope. While Walter White and Tony Soprano do not physically wear masks, they are clearly passing as honest American citizens while exercising their entrepreneurial skills in a capitalist society. Orange Is the New Black offers a relatively new trope to replace/enhance the mask—the uniform. This paper will explore some history of passing in pop culture and literature. It will look at the tropes that are obvious (the mask) as well as tropes that are newer (the uniform as symbolic identity) and often less visible. The reader will see this issue is both pervasive and complex and in need of further analysis. It examines identity as a fluid state which may change from the private sphere to the public sphere. If you are looking for a definitive right or wrong, you will not find it here.

While masks and masking have a lengthy history of symbolizing passing, a newer trope in pop culture is the use of clothing, specifically the uniform. The heroes and villains of comic books are identifiable by their costumes, as are doctors, nurses, police, etc. Superman’s iconic “S” has been appropriated by countless sources, including every t-shirt maker in the world. The orange jumpsuit of the incarcerated (jail inmates, Guantanamo) is contrasted with the dress blues/tans of the military/police/corrections officers. We recognize the character under the mask/uniform by what we expect them to be. We expect uniformed officers to be fair, brave and honest. We expect inmates to be lower class non-individuals. When we admonish people to “not judge a book by its cover,” we are referring to passing.

Let us begin with a definition of passing—no easy deal. Passing is when someone knowingly allows someone else to believe a lie about their identity without correcting them. This could be a mentally ill person who hides, or simply never mentions, their bipolar disorder; a person disabled with post-polio syndrome who allows people to assume that she just twisted her leg recently; a light-skinned African American who does not correct an employer who believes that said employee is white; the gay high school football player who allows his fellow teammates to assume he is heterosexual. It can also be even more nuanced than this. How about the housewife who pretends to be happy while having affairs on the side? The abused child who says he fell down the stairs? The model who claims to be ten years younger than her actual age? Every scholarly text on passing offers a different definition. Passing is undoubtedly complex.

Perhaps the best formal definition comes from scholar Julie Cary Nerad in her book Passing Interest: Racial Passing in U.S. Novels, Memoirs, Television and Film: 1990-2000 (SUNY Press, 2014). Nerad states that passing:

is now understood by many scholars as synonymous with performance; it is the iteration of a set of behaviors, cultural codes, language, etc. ascribed to a specific identity category, such as race, gender, sexuality, class, religion and so on (9).

This research on passing formally began at the New York University Faculty Resource Network in June 2014 where I was a scholar-in-residence. A colleague interested in my topic pointed me to sociologist Harold Garfinkle as the “seminal” work in passing. Indeed, it provided an historical launchpad for this exploration. Garfinkle’s opening words are: “Every society exerts close controls over the transfers of persons from one status to another” (58). Dealing with transgendered individuals, he wrote:

The work of achieving and making secure their rights to live in the elected sex status while providing for the possibility of detection and ruin carried out within thee socially constructed conditions in which this work occurred I shall call “passing” (60).

Of course, the concept of passing predates Garfinkle’s sociological theory; I had long understood passing as what individuals in the black community did if their pigmentation and facial features were “light” enough to “pass” for white. This particular passing required a conscious choice which held both dangers and loss as well as benefits. Black or biracial authors wrote about this in fiction as far back as Charles Chestnutt’s The House Behind the Cedars (1900), Walter White’s novel Flight (1925), and Jessie Fausett’s novel Plum Bun (1928). Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel Passing deals with the issue of racial passing while also suggesting homosexual passing in the unspoken attraction between Irene and Clare. Queer Theory has invited a reassessment of dated novels and is important in understanding passing as a complex social strategy. While it often provides agency, it also suggests psychological stress.

Roughly twenty years following these African American novels, John T. Burma writes in the American Journal of Sociology (1946), an article entitled “The Measurement of Negro ‘Passing’.” He states that:

whenever a minority group is oppressed or is the subject of discrimination, some individual members attempt to escape by losing their identity with the minority and becoming absorbed into the majority. In the United States the Negro is such a minority group (18).

Burma points out what was seldom obvious in 1946, that being a Negro is not simply biological—it is also a legal and a social matter. The “one-drop rule,” also known as hypodescent laws, made sure of that. The one-drop rule was not adopted as law in the U.S. until the 20th century and was upheld by the Supreme Court in Plessy vs. Ferguson which allowed “separate but equal” public facilities.

In Race Passing and American Individualism, Kathleen Pfeiffer states that the “motivation for passing heightened after South Carolina’s 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson” (2003, p. 30). Pfeiffer examines passing narratives of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and states that “throughout the works studied here, the passing figures stand outside their own reality…” (2003, p.3). Later in the text Pfeiffer quotes Werner Sollors’ 1997 book Neither Black Nor White Yet Both that passing:

can thus justly be described as a social invention, as a ‘fiction of law and action’ (Mark Twain) that makes one part of a person’s ancestry real, essential and defining, and other parts accidental, mask-like and insignificant… (5).

We are getting a look into the conflicts between the public sphere and the private sphere. The mention of the mask reminds one of the use of masks as a literary trope. Masking is covering up, while unmasking is to reveal the true identity or nature of someone or something. As T.S. Eliot states in his 1920 poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” I put on a “face to meet the faces that you meet.” This line suggests changing one’s demeanor to reflect one’s surroundings as opposed to reflecting oneself. This chameleonic ability is happily explored by social scientists and metaphored by poets.

While we understand that passing often deals with race, sociologists Harold Garfinkle and Erving Goffman broadened the study. In his seminal work Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity, Goffman takes passing to a level beyond race and sexual identity. He states:

It is apparent that if a stigmatizing affliction possessed by an individual is known to no one, including himself…then the sociologist has no interest in it…. Where the stigma is nicely invisible and known only to the person who possesses it, who tells no one, then here again is a matter of minor concern in the study of passing (73).

Goffman admits both cases are difficult to assess; outside of these extremes is a huge, nuanced middle ground. Goffman states that:

there are important stigmas, such as the ones that prostitutes, thieves, homosexuals, beggars, and drug addicts have, which require the individual to be carefully secret his failing about to one class of persons, the police, while systematically exposing himself to other classes of persons, namely clients, fences, and the like (73).

His 1959 work The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life uses dramaturgical principles to explain social interactions. He states that his ideas provide a “framework that can be applied to any concrete social establishment…” (xi). He explains that the “perspective employed in this report is that of the theatrical performance; the principles derived are dramaturgical ones” (xi). The reader can take Goffman’s principles and apply them to almost all later theories of passing because passing is performance. Performance is masking or acting—a popular literary tool. Paul Dunbar (1872-1906), the first African American to attempt to make a living by his writing, says it best in his poem “We Wear the Masks.” Dunbar writes:

We wear the mask that grins and lies

It hides our cheeks and shades our eye,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Dunbar is discussing the need to camouflage one’s true feelings, to “pass” as happy in order to keep those in power comfortable.

Elaine K. Ginsberg, in the introduction to her book Passing and the Fictions of Identity, writes that (slaves) passing was a “transgressing not only of legal boundaries” but also of “cultural boundaries as well” (1). Ginsberg speaks of the many slaves who:

passed out of slavery moved from a category of subordination and oppression to one of freedom and privilege, a movement that interrogated and thus threatened the system of racial categories and hierarchies established by social custom and legitimated by the law (1-2).

Essentially, says Ginsberg, passing is about:

identities: their creation or imposition, their adoption or rejection, their accompanying rewards or penalties. Passing is also about the boundaries established between identity categories and about the individual and cultural anxieties induced by boundary crossing. Finally, passing is about specularity: the visible and the invisible, the seen and the unseen (2).

Erving Goffman would agree with Elaine Ginsberg. Again we visit Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy and see identities centered around being able-bodied and therefore “whole.” A disabled president might be seen or perceived as weak (not powerful) and not whole. The private sphere and the public sphere are in conflict.

Ginsberg adds that both:

the process and the discourse of passing challenge the essentialism that is often the foundation of identity politics, a challenge that may be seen as either threatening or liberating but in either instance discloses the truth that identities are not singularly true or false but multiple and contingent (4).

Identity formation is a huge topic. Osborne and Frost write in “The Anatomy of Hatred: Pathways to the Construction of Human Hatred” that:

there are multiple pathways to Self (Identity)—biological, psychodynamic, emotional, cognitive, and social—we must look holistically at the emergence of Self with in the crucible of social reality… (13).

They later state that “the social dynamics involved in identity formation may be of special import” (14). It is the social dynamics which force people into multiple and contingent identities. This is passing—the adaptation of one’s identity (that chameleonic quality/ability) to a given social situation. Sometimes it is conscious, such as racial, although there are notable exceptions. Sometimes it is unconscious (individual has not come out to themselves yet or accepted their disability, such as mental illness.) Either way, passing provides agency.

In “Sliding under the Radar” Fuller, Chang and Rubin, writing in the Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, posit that:

many stigmatized groups live their lives hiding or compartmentalizing aspects of themselves in order to pass as members of the more privileged majority. The term “passing has been used to describe the process of being recognized by others as a member of a social identity group that is incongruent with one’s self-identity (128).

The authors cite Goffman and go on to discuss passing “among sexual minorities” (129). Essentially, they are examining the conscious disconnect between the private sphere and the public sphere; this disconnect is where the performance of passing comes in.

The man LIFE Magazine described as “America’s number one intellectual fascist,” was a black man named Lawrence Dennis, who passed as white his whole life. The price of passing included permanent separation from his home and family of origin. 2 The reward was a Yale education and a job in the U.S. State Department. He hobnobbed, because he was passing as white, with John D. Rockefeller, Maynard Keynes, and Joseph P. Kennedy. Dennis was the darling of modernist poet Ezra Pound. Dennis was passing, and, one must admit, the story is lusciously subversive. As the story goes, he allegedly let his nappy hair grow out while on his deathbed—just to give the finger to the establishment. 3

Characters on television shows have frequently been passers. Upon re-visiting the critically acclaimed television series China Beach (1988-91), one sees passing all over the place despite the military uniform(s). Perhaps the only character not passing is Marg Helgenberger’s entrepreneurial prostitute Karen Charlene “K.C.” Koloski who has fun (sexually) and makes lots of money off the stresses of the Vietnam War. What you see is what you get. African American character Samuel Beckett, working the Graves Registration unit, states in a speech to a roomful of dead soldiers, that he is “turning white.” He finds racial identity confusing when two white chicks are joyously singing Motown hits to a rowdy audience of soldiers. The name Samuel Beckett, of course, references the Irish playwright who authored the iconic Waiting for Godot, part of theater of the absurd. What is war, after all, but absurdity passing for strength, righteousness and patriotism? One of the major themes of this television show, which aired long before post- traumatic stress disorder was a regular subject for public discourse, was PTSD. Ahead of its time, China Beach only survived four seasons on network TV, presumably because it dealt far too honestly with the vicious absurdity of the Vietnam War. Conversely, M A S H aired successfully for eleven seasons, far longer than the Korean Conflict it portrayed, by using comedy to critique, yet never overtly protest, America’s role in the Cold War. “China Beach” was serious, graphic, and critical. The United States was not ready to deal with the personality changes inherent in PTSD in the public sphere until we were directly attacked (victimized/traumatized) on September 11, 2001. That is when PTSD finally entered our public discourse. People with PTSD, such as rape victims, had to do their best to pass as “normal” before that.

In American culture it is elite to wear a military uniform, which symbolizes authority and power. Might that be the reason there are so many cases of “stolen valor,” a form of passing rampant since the Vietnam Era? Stolen Valor, as defined by Thomas Ruyle in the June 16, 2010 Stars and Stripes, is “people falsely claiming military awards or badges they did not earn, service they did not perform, Prisoner of War experiences that never happened….” Clearly this can range from a total fabrication by a civilian to a veteran who wants to make his or her experiences sound more brave and/or glamorous. One version of the Stolen Valor law was passed in 2005 but was later struck down by the Supreme Court in 2012, according to the website Military.com (dated 3 June 2013). Bryant Jordan writes that President Obama “Signs a New Stolen Valor Act”. The new law specifically limits the wearing of unearned military medals as well as lying about service for financial gain, such as a reduced mortgage rate. This form of passing, stolen valor, is a slap at every honest military veteran who serves or served our country.

In the United States we also tend to put athletes on the proverbial pedestal and have often been let down. Some famous athletes are passing as the real deal. Think Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez and Lance Armstrong. How about last season’s NFL scandal called Deflategate? Quarterback Tom Brady allegedly allowed the footballs deflated to his liking before the 2014 Superbowl. He publicly denied any knowledge of this and conveniently destroyed his cellphone the day before the formal hearing on this issue. The cover of the July 29, 2015 Daily News reads “Brady ordered cell destroyed just before sitdown with NFL: YOU PHONEY!” Many Americans revere the sports uniform, much like the military person’s, as a sign of honesty and integrity. Alex Rodriguez staunchly denied taking human growth hormone (HGH) for years until he was “outed” (there’s that gay term again). This is another form of passing in the public sphere.

“Coming out”—a term once the exclusive purview of homosexuals—is now the au courant word for almost any kind of passage/transition. Coming out as disabled is more of a private identity struggle than it is a public declaration. The intersections between passing and disability are the many stories of disabled people passing as abled, which is well-documented in scholarly literature and memoir. As Nancy Mairs states in Waist-High in the World:

For the moment, what’s important to me is not the outstanding but the ordinary: the normally unconscious attitudes that chill the social climate for people marked out by disability (99).

It is social climate that drives decisions about passing.

Because disability is perceived to make an individual “less than,” many people with disabilities choose to hide them or keep them private (secret), if possible. Franklin Delano Roosevelt could have easily been our “first disabled president,” but he chose to publicly pass as able-bodied.

FDR is our first Passer-in-Chief. The same is true of John F. Kennedy, who suffered from Addison’s disease, a potentially life-threatening disease, but vehemently denied it. In the case of FDR, the press was complicit in covering up his disability; in JFK’s case, he simply lied. 4

Coming out as disabled is never easy because it is both an internal and an external struggle. As a political issue, both FDR and JFK risked the White House if their disabilities were generally known. Passing as abled gives each man political agency. It becomes a social issue when we examine public spaces, which, as often as not, are manufactured to limit mobility. It becomes a matter of public policy when the ADA is invoked. Passing is usually done for a chance at a better life, to avoid discrimination. The cornerstone example of this is an African American passing for white during the Jim Crow era. It is where the usage of the term “passing” comes from in the United States.

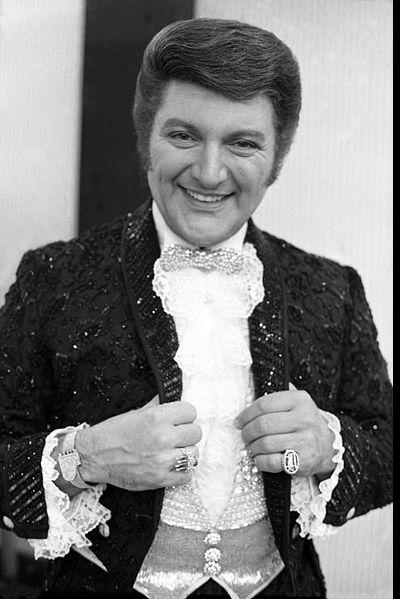

Historically, passing is nothing new. Liberace, Mr. Showmanship, successfully sued two newspapers for saying (the obvious) that he was a homosexual.

Did he ever really pass as straight? Heartthrob Rock Hudson defended his heterosexuality until his death from AIDS. In the public sphere how many republicans chant family values and anti-gay rhetoric only to be caught in a bathroom stall or paying off a same sex lover? Historically speaking, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt passed as able-bodied to the general population of America, who believed he heroically overcame polio through sheer will power. 5 Supposedly he did this because the country could not envision a president with a disability. FDR passed as able-bodied, performing ableness with the help of aides and his son, and with complicity with the press. Similarly, John F. Kennedy, Jr. suffered privately with Addison’s disease, an autoimmune disorder which could have been fatal. JFK publically denied any illness and won the presidency on his youth, vim and vigor. 6 I wonder if the country today is enlightened enough to embrace a president with a disability?

There are many movies, often adapted from novels, which deal with passing as a racial issue. The 1933 Fannie Hurst novel Imitation of Life, which had two film incarnations, starring Claudette Colbert (1934) and Lana Turner (1951), deals directly with racial passing and subliminally with other types of passing. Pinky, a powerful film by Elia Kazan (1949), does so, too. All three films were met with both acclaim and controversy when released. More recently Philip Roth’s novel The Human Stain (2000) deals ostensibly with journalist Anatole Broyard’s deliberate passing as a white man (Roth denies this). It was adapted into a film in 2003 starring Anthony Hopkins. This is the story of a black college professor Coleman Silk who passes as a white Jew since his stint in the Navy, where he passed as white. Here we enter the dichotomy of the public sphere and the private sphere. Jewish novelist Fannie Hurst’s novel Imitation of Life is actually about parallel passing stories. A young woman passes as white to get ahead (actually, simply to get work to support herself and her biracial daughter). Her daughter abandons her mother. The protagonist, who becomes successful at the cost of all her personal relationships, is actually passing as a “good mother.” All the characters in this novel are passing in one way or another by lying to themselves (private sphere) and to the public (public sphere).

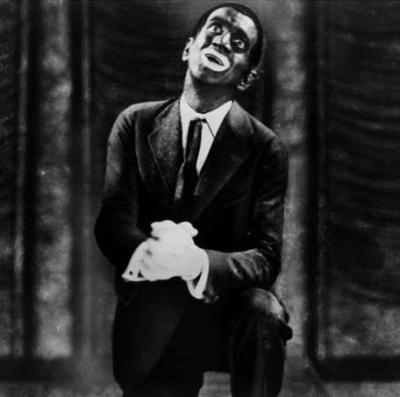

Jewish blackface performer Al Jolson is singing “Mammy” to the camera in the world’s first talking film, The Jazz Singer (1927).

He was a Jew publically performing blackness. Some critics feel that he performed in blackface to both enhance his whiteness and mask his Jewishness. He was the highest paid entertainer in 1930 America, and the first popular singer to make a spectacle out of singing a song (see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PIaj7FNHnjQ). The people loved him, and he was an active advocate for African American performers. Is Al Jolson “passing” for black? Is he lying by not announcing his Jewishness? 7

Are you familiar with the true story of Billy Tipton, the jazz musician, who was only discovered to be a female after his death?

He explained (lied) his sterility on a horrific car accident, which he claimed broke several ribs and mutilated his genitals. He adopted two boys with his fifth wife. None of his wives or sons were aware his womanhood. Was Tipton was performing lesbianism? S/he was born Dorothy Lucille Tipton in Oklahoma City. She joined an all-male band and began dressing “manly” to fit in. Clothing here is acting as a mask, yet he adopted male clothing as a marker of his identity.

It is probably doing a disservice to ourselves as Americans to oversimplify issues that cannot, by their very nature, be simple. I have shared examples of passing in America that demonstrate that this behavior is neither new nor unusual. Yes, the image of Rachel Dolezal has meaning. She is consciously constructing blackness with, I believe, integrity and good intentions. If images produce an impact, I believe that the center of all this spectacle around a young academic is the two white parents, estranged from their grown daughter, who publicly “outed” her.

Even the rhetoric we use in this discussion is complex, as outing began in the gay community and was then adopted by the disability community. It assumes that truths are finally being put forth. As the mainstream media and the Twitterverse made a spectacle of Rachel Dolezal passing as black, we must ask how deeply have we delved? Is it a sufficient reason to deplore any individual for lying when people lie about their age/weight/income/alcohol intake on a regular basis?

On July 6, 2015, Inside Higher Ed Daily News Update featured an article entitled “Fake Cherokee?” by Scott Jaschik about the scrutiny surrounding Andrea Smith, Associate Professor of Media and Cultural Studies at University of California at Riverside. Smith, unlike Dolezal, is a prominent scholar and activist in American Indian Studies. Because California law specifically denies the consideration of race in tenure/hiring, Smith could not have lied on her application. Digging deeper, on July 1, 2015 David Shorter wrote in Indian Country Today “Four Words for Andrea Smith: I’m Not an Indian.” Apparently Smith has claimed an Indian heritage which is not rightfully hers. In the article Shorter writes, “Some attention has been rightfully paid to the long history of people ‘playing Indian’…as well.” “Playing Indian” suggests masking and performance in the public sphere. A link in the article brought me to a spoof of a famous/infamous song from Irving Berlin’s 1946 musical Annie Get Your Gun entitled “I’m an Indian, Too.” The Berlin song states that funny names and fashion accouterments “prove” that you are an Indian. The lyrics read:

Just like Rising Moon, Falling Pants, Running Nose

Like those Indians

I’m an Indian too….

And I’ll wear moccasins, wampum beads, feather hats

Which will go to prove

I’m an Indian too.

Note: check out the spoof of this song by 1491 on Youtube.

On July 7, 2015, JSTOR DAILY headline ran “Linguists Crack Down on Catfishing” by Chi Luu. The article, entitled “Gone (Cat) Fishing: How Language Detectives Tackle Online Anonymity” deals with the conscious creation of false online identities for purposes of scam and/or romance. Catfishing is not new; it has always been done. This is certainly a form of passing which covers both the public and private spheres. And it is international.

Academic Rachel Dolezal, an instructor in Africana Studies, passed for black in the Spokane NAACP, while ostensibly coloring her skin and curling her hair. When she was “outed” by her parents, one might have thought that passing was something outrageously new that Dolezal discovered and perpetrated on the community. The Twitterverse lit up with clever lines designed to hurt, including a photo of a slightly orange-tinged Dolezal captioned “orange is indeed the new black.” In the July 6, 2015 Chronicle Review Sarah Valentine wrote the article “When I Was White” in which she writes about “the legitimacy of ‘transracial’ experience.” Valentine states that “for most of my life, I didn’t know that my biological father was black.” This reminds me of a PBS POV film (first aired 3-23-15) entitled “Little White Lies” by Lacey Schwartz. Schwartz was raised as an older sister to white brothers and was told she had Jewish heritage. The result is having to work out a new identity in one’s 20s or even 30s. This is where passing becomes complicated. A similar case is the daughter of* New York Times* journalist Anatole Broyard. Bliss Broyard was only informed that her famous father was half black shortly before his death; she had spent 24 years as a white girl. 8

Scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. writes in the introduction to Black Cool: One Thousand Streams of Blackness by Rebecca Walker and Henry Gates (2012) that blacks “are not a monolith but we are a community.” There are a “multiplicity of ways in which blackness is both definitive and interpretive, confining and liberating, imposed and embraced, perceived and, even at times, ignored” (x). This statement holds true for the gay community, the disabled community. Passing is not new. Lying is not new. Spectacle is not new, but it does distract from the core issues at hand. Today Rachel Dolezal says she is comfortable with her identity (see: http://on.today.com/1qMSgDEhttp://on.today.com/1qMSgDEhttp://on.today.com/1qMSgDEhttp://on.today.com/1qMSgDEhttp://on.today.com/1qMSgDE). Why are we not comfortable, too?

Footnotes

- Summer of 2015 spent at NYUs Faculty Resource Network as a scholar-in-residence. My African American friends were outraged because Dolezal did not “earn” the right to claim blackness.

- The history of passing as well as the significant losses suffered by people passing is explored extensively in Allyson Hobbs’ 2014 book A Chosen Exile.

- The full story of Lawrence Dennis is covered in Gerald Horne’s book The Color of Fascism: Lawrence Dennis, Racial Passing and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism in the United States (2006).

- The information about FDR is extensively covered in Ken Burn’s documentary The Roosevelts: An Intimate Portrait. Information on JFK obtained from CNNs Race to the White House, narrated by Kevin Spacey..

- Information about FDR comes from Ken Burns’ film The Roosevelts: An Intimate Portrait.

- Information on JFK obtained from CNNs Race to the White House, narrated by Kevin Spacey.

- For a subversive look at blackface watch Spike Lee’s masterpiece **Bamboozled. My lips are sealed*. Spike Lee also adapted a play to film entitled Passing Strange.

- See Bliss Broyard’s One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life - A Story of Race and Family Secrets, Back Bay Books 2008.

References

Barker, Revel. Crying All the Way to the Bank: Liberace v Cassandra and the Daily Mirror (famous trials). London: Revel Baker, 2009. Print.

Broyard, Bliss. One Drop: My Father’s Hidden Life—A Story of Race and Family Secrets. New York: Back Bay, 2007. Print.

Burma, John H. “The Measurement of Negro Passing.” American Journal of Sociology 52.1 (1946): 18-22. Print. Passing as a legal issue in racial passing

China Beach. Screenplay by William Broyles, Jr. 1988. Warner Bros. Entertainment, 2013. DVD.

Elam, Michele. “Passing in the Post-Race Era: Danzy Senna, Philip Roth, and Colson Whitehead.” African American Review 41.4 (2007): 749-68. Print.

Fuller, C. B., D. F. Chang, and L. R. Rubin. “Sliding Under the Radar: Passing and Power among Sexual Minorities.” Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling 3.2 (2009): 128-51. Print.

Garfinkle, Harold. “Passing and the Managed Achievement of Sex Status in an ‘Intersexed Person.’” The Transgender Studies Reader. Ed. Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. NY: Routledge, 2006. 58-93. Print.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “The Passing of Anatole Broyard.” Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man. New York: Random House, 1997. 180-214. Print.

Ginsberg, Elaine K., ed. Passing and the Fictions of Identity. Durham: Duke UP, 1996. Print.

Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor, 1959. Print. –––-. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Touchstone, 1963. Print.

Hobbs, Allyson. A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2014. Print.

Horne, Gerald. The Color of Fascism: Lawrence Dennis, Racial Passing and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism. New York: NYU P, 2009. Print.

Hurst, Fannie. Imitation of Life. Ed. Daniel Itzkovitz. Durham: Duke UP, 2004. Print.

Imitation of Life. Dir. Douglas Sirk. 1959. Universal. DVD.

Imitation of Life. Dir. John M. Stahl. 1934. Universal Studios. DVD.

Larsen, Nella. Quicksand and Passing. New York: Penguin, 1929. Print.

Little White Lies. Dir. Lacey Schwatrz. Independent Lens. Dir. Lacey Schwartz. Public Broadcasting System. PBS, 23 Mar. 2015. Television.

Mairs, Nancy. Waist-High in the World: A Life Among the Nondisabled. Boston: Beacon, 1996. Print.

“Murder House.” Prod. Netflix. American Horror Story. Perf. Dylan McDermott and Jessica Lange. Netflix. 2011. Television.

Nerad, Julie Cary, ed. Passing Interest: Racial Passing in U.S. Novels, Memoirs, Television and Film 1990-2010. Albany: SUNY, 2014. Print.

Osborne, Randall E., and Christopher J. Frost. “The Anatomy of Hatred: Multiple Pathways to the Construction of Human Hatred.” Humanity and Society 28.1 (2004): 5-23. Print.

Passing Strange. Dir. Spike Lee. 2008. Apple Core and 40 Acres and a Mule, 2008. DVD. Screenwriter is STEW.

Pfeiffer, Kathleen. Race, Passing and American Individualism. Amherst: U Mass P, 2003. Print.

Race for the White House. Narr. Kevin Spacey. CNN. CNN, 2016. Television.

The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. By Geoffrey C. Ward. Public Broadcasting System. PBS, 2014. Television.

Roth, Philip. The Human Stain. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. Print.

Sollors, Werner. Beyond Ethnicity: Consent and Descent in American Culture. New York: Oford UP, 1986. Print.

Valentine, Sarah. “When I was White.” Chronicle Review (2015): n. pag. Print.

Webber, Bruce. “Harold Garfinkle, a Common-Sense Sociologist, Dies at 93.” New York Times 3 May 2011: n. pag. Print.