“Year by year, as Family went on, they had me gradually grow up. But it was like they didn’t really want me to.” ~ Kristy McNichol (qtd. in Darvi, p. 181)

As the youngest child in my family, when we worked together to make board puzzles (we would trade them back and forth with Aunt Winnie’s family), I’d sometimes grab one piece and hide it away in my palm until all the others were put in place, so I could claim “Final piece!”

In an obscure 45, “Kristy for Christmas,” released in 1979 when popular actress Kristy McNichol was playing 15-year-old tomboy Buddy on the ABC-TV series Family, Craig Malon discourses in rockabilly rhyme about how badly he’d like “Ms. McNichol” as a gift under his tree that year. Craig wasn’t alone in wanting Kristy, or a piece of her, during the 1970s.

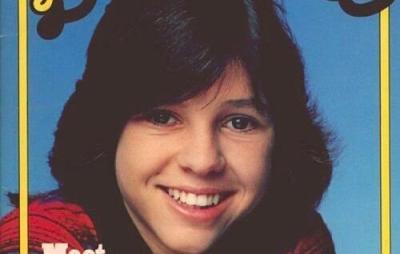

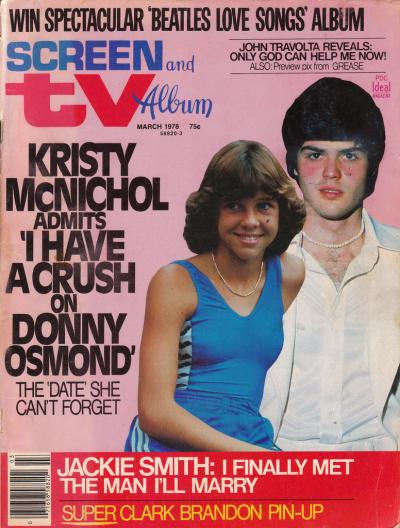

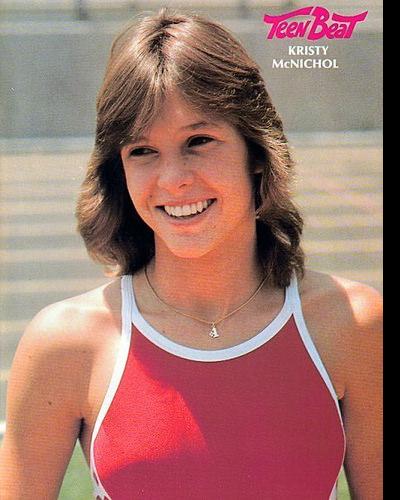

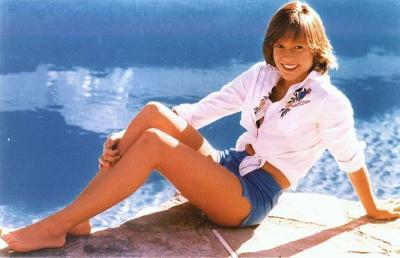

Decades prior to 24-hour cable TV media saturation and the preeminence of the selfie, McNichol’s photo was slap dashed onto dozens of covers of magazines mainly aimed at selling pieces of Kristy to teenagers (Tiger Beat, Teen Beat, etal.), though none more aesthetically-70s than her first appearance on Scholastic Books’ Dynamite magazine, but also in concocted stories thinly linked to publicists’ statement or even her TV characters’ fetishes (e.g., Buddy’s adoration of Donny Osmond), stories that inevitably propagated a craving for Kristy McNichol among teenaged boys and girls. The clearly photo-shopped pictures of Kristy being “hugged” by then-superstars and would-be dates (much older ones at that) like Osmond or Glen Campbell illustrate the hard-to-satiate desire that magazines such as Teen Beat deigned to sell us.

Kristy even became a toy…

“You can pretend she’s a buddy” ~ from television commercial for Mego’s Buddy doll

Once, in a fifth grade haze, induced and enhanced by several mid-70s ABC After School Specials starring Kristy McNichol as the best friend-girl you could ever want, I dreamt I was in an airport and that Kristy and I walked towards one another across a crowded terminal (I had never been in an actual airport!) and that the closer she approached, the more she smiled, and in that moment our futures beyond fifth and seventh grade were joined like interlocking pieces of a puzzle. I kept my dream to myself because—well, because it is silly; and the more prominent blogging and chatting and forumming has become, the more I found that such a crush on Kristy was rather common; millions of us had stolen pieces of Kristy in the 1970s and still crave to own remnants of her childhood self.

Today, reproductions of photos of Kristy from the 1970s in her ABC Battle of the Network Stars outfits— particularly her red or blue one-piece swimsuits—sell for a nice sum on eBay. As do individual doll parts from the late 70s Mego toy.

Anything to have a piece of Kristy: Everybody wants you to be a little buddy forever.

Because we all wanted pieces of Kristy, she never quite had the pieces of herself to put herself together, complete.

I notice the puzzle coming together amidst the busy, essaying hands of my family, and peak down at my clenched palm to the piece I’d hidden away, secure in my knowledge that I will claim the achievement of fitting together what will soon become that suddenly-sought-after, final piece.

“I’ve had to grow up quickly. Everyone is at you—lights, hair, camera, directors, producers—and there is only one of me. They are all pulling at me for different reasons.” (McNichol qtd in Jarvis)

White Dog, directed by Samuel Fuller, is a fascinating film that many people first saw when it “premiered” on Showtime in the early 1980s after having been ditched by Paramount Pictures for theatrical release. (In the movie, the term “white dog” describes a dog that has been trained by whites to hate and attack black people.) According to J. Hoberman, Paramount tested the film in just five theaters, deciding at that time to shelve the film, with its primary airings later coming on cable TV. Hoberman’s notes indicate that the company was advised against releasing the film because it might promote the breeding and training of “(more) white dogs” (Hoberman). The film fit a lineage of animals-run-amok fare such as Jaws, Grizzly, Prophecy, and Day of the Animals, each of which, to varying artistic degrees, contain social commentary on such themes as consumerism, industrial waste, or the nature of fear itself.

In his 2008 Criterion Collection DVD liner notes, Armond White makes such a case for the lesser-known White Dog, as well, in that “[Director Samuel] Fuller utilized the legendary figure of the attack dog in order to expose racism and its casual, deliberate indoctrination.” In sum, the film, based loosely on a story by Romain Gary, features McNichol as Julie, a struggling Hollywood actress who late one night hits a dog with her car and out of guilt makes sure it receives medical attention. At the vet’s, the dog awakens to Julie’s endearing gaze (shown from the dog’s point of view) and it and we become her loyal companions.

She decides to keep him after a futile search to find its owner. The dog turns out to have been trained (we viewers learn) to attack black-skinned people on sight, though Julie is innocent that such a behavior could even exist, and she takes the dog to an animal training center to discover its behavioral issues. An African-American trainer named Keys (played by Paul Winfield) quickly identifies the root of the dog’s vicious attacks and attempts to a) un-indoctrinate the dog, and b) convince Julie that racism is culturally ingrained.

My reading of this conflict parallels the dog’s social indoctrination with the social construction of Kristy McNichol’s public persona, each of which resulted in the erasure of their authentic selves. Magazines such as this excerpt from a 1978 Tiger Beat enjoyed the magazine-selling activity of constructing a McNichol persona to feed the developing anxieties of its readership:

For the past two seasons, Kristy McNichol has been portraying the part of Buddy on the ABC series “Family.” When the show first started, Kristy was playing a 13-year-old, and now, two years later she is maturing into a very lovely young woman of 15! So it looks like Kristy’s growing up—and very nicely at that! By developing the character of Buddy, who started out as a full-fledged tomboy, into a sensitive young lady, she’s improving her best talent—acting! (“Kristy and Love!”, p. 68)

In the film, the dog is a conundrum that confounds Julie, and serves as our lens for analyzing McNichol’s fragmented self. There is something beautiful, pure, and protective about the dog—he saves her from a burglar and would-be sexual predator, and the dog’s sheen reflects the artificial world of the protagonists’ career as a struggling actress who accepts bit parts in movies and commercials while awaiting her big break. I’ve also come to see the tension in the film as a mirror of what at the time was an unrelenting media celebration of Kristy McNichol’s body— reflecting both a media-groomed heteronormative feminine sensuality while maintaining aspects of her iconic TV character Buddy’s tomboyish and friend-girl aura.

While the white dog’s racist conditioning makes sense to viewers (because we have seen exposition point of view shots of its violent tendencies outside of Julie’s perspective), the reasoning behind the dog’s outbursts confounds Julie and contributes to her emotional breakdowns. It is almost as if we see Julie’s disillusionment with her once-innocuous and pure dog parallel McNichol’s lack of control over her public image and identity.

[

Because the truth behind the dog’s socialized behaviors eludes Julie for most of the film, she becomes an essentially childlike understudy on the stage of her own adulthood, a quality that is best illustrated by a highly-stylized “set piece” in which Julie and her African-American friend and co-star are filmed in a gondola, with scenery of Venice projected behind them; in the foreground, Julie’s dog watches as the illusion is created.

Due to its conditioning, the dog attacks Julie’s co-star. As a result, Julie feels guilt and has to reckon with how something so beautiful could also be so violent, and whether the dog can be saved from its behaviors even while she ignores the possibility linking its actions to social construction. These personal and public anxieties reflect a burial of McNichol’s self as the iconic “Buddy” on the TV show Family—in particular, the “intrusion” of her emerging socially-constructed feminine adulthood (akin to the intrusion of the baffling ‘white dog’), which mirror McNichol’s own much-publicized breakdowns during the early- to late-1980s.

“When they said, ‘Cut,’ I became this sad little lost animal in the darkness” (McNichol qtd. in Haller).

Julie’s naiveté (also justifiably interpreted as confusion or self-denial) mirrors McNichol’s own struggle to see how her identity had been a media construct, at the time when she began to experience the emergence of her own sexual identity which conflicted with this carefully-groomed and sanctioned construct. This “puzzled identity” became part of an ongoing Hollywood mystery-narrative, as mainstream magazines like People Weekly and Us explored (usually sympathetically, given McNichol’s likeable stature and popularity in the TV show Empty Nest at the time) whether her erratic behaviors were linked to alcohol and drugs, or more simply and perhaps less problematically, from a mainstream readers’ perspective, workaholism, as stated in this excerpt from a 1983 People cover article: “Kristy realizes she must follow a prescription from her doctors: ‘She’s got to stay on a strict diet’—a work diet—‘not being so involved in her career and just take time out for herself.’” The article casually states, “Precisely what McNichol suffers from is not clear” (Jarvis). Later stories in this vein provide more intense scrutiny into the physio- or biological nature of McNichol’s breakdowns, attributing them to first manic depression, and then bipolar disorder. There was also a bit more probing into McNichol’s family dysfunction: a mother who sought vicarious stardom through her children, and a daughter who was, to reiterate the magazine’s conclusion, simply overworked: “From the time I was very young, I was a professional, making money and assuming responsibilities,” she says. “I didn’t live the life of a child. I was living the life of a 30-year-old. I was like a miniature adult. I’d go off to work every day with a little briefcase.” (qtd. in Haller) These words from McNichol are unsettling, but they were also more comforting (to a public that still struggled with its acceptance of sexual diversity) than what may have been lying underneath the surface, a struggle to establish her authentic sexual identity. At one point, the interview touches upon McNichol’s grooming, which echoes the social conditioning of the white dog in the film. McNichol said: “…not having a childhood, coming from a broken home, not going to school, not going to the prom, all these people telling me to do this and do that and not having any say-so,” reinforcing how (as stated by Julie during her epiphany in the film) the “two-legged bastards” whom she learns owned the white dog had groomed him: “telling [him] to do this and do that and not having any say-so.”

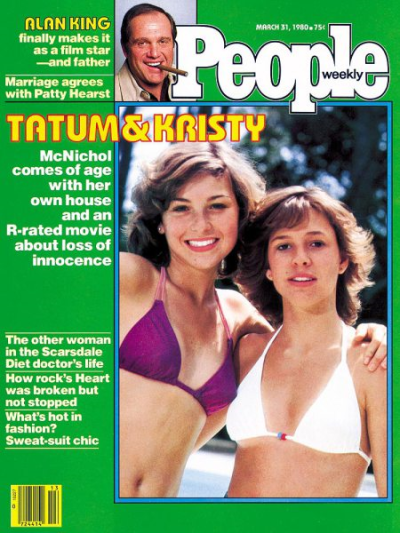

Prior to her to attempts to break into adult roles such as White Dog, McNichol’s authentic and heartbreaking rendering of the loss of innocence in the 1980 film Little Darlings revealed a sensitive young-adult performance that only adds to the irony of how strained was her transition to adulthood; that the film promotes a disillusioning and heteronormative sexual transition to womanhood could only have fed into McNichol’s embattled psyche, not to mention that it catapulted her further towards the role of unwitting feminine sex symbol, as depicted on the iconic March 1980 cover of People Weekly.

In White Dog, Julie’s gradual self-understanding in the film serves as a lens into the real-life McNichol’s suppressed self-discoveries, and is bound with the fate of the sympathetic white dog who we sense in the scene’s final Leone-esque showdown has begun to recognize his own conditioning, after having a brief taste of his liberation when Keys appears to have freed him through his intense training methods.

Such moments as this tender embrace from earlier in the film will resonate for viewers open to this interpretation of the two characters, who serve as fictive representations of Kristy McNichol’s own submerged and oppressed identity, the root causes for which we consumers can claim partial responsibility, in our harried and adolescent desire to own our very personal piece of Kristy—a million fragmented bits of posters, records, Tiger Beat clippings, revealing photos of legs and breasts, and dolls still Mint-in-the-Box for us to gaze at on our shelves and retro-basement walls.

Unlike the dozens of sensational, fictive Tiger Beat cover articles, and with much less attention than their cover stories about Kristy’s emotional struggles (“To Hell and Back”), McNichol’s official coming out was covered in two brief reports featured in 2012 in People magazine. In the first, she states, “At 50, I want to be open about who I am.” A week later, her publicist adds, “She hopes that coming out can help kids who need support. She would like to help others who feel different.” (McNeil)

The puzzle that everyone worked so hard to make is nearly complete, the family members scouring the coffee table, feeling in between sofa seats, or lifting the puzzle board gently so as not to disrupt the pre-determined picture we’ve been trying hard to recreate— “Where can it be? Aunt Winnie said it was complete when she gave it to us” – when I open my palm, heart beating rapidly, to display how I’d harbored the final, elusive piece, only to find that it’s fallen away from my hand, thirty-five years suddenly lost, like a whisper of affection in a torrent of pain.

References

Darvi, Andrea. Pretty Babies: An Insider’s Look at the World of the Hollywood Child Star. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983.

Haller, Scott. “I Was Crying All the Time.” People Weekly, April 3, 1989. http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0„20119939,00.html.

Hoberman, J. “White Dog: Sam Fuller Unmuzzled.” Criterion Collection DVD Liner Notes. 2008. http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/848-white-dog-fuller-vs-racism.

Jarvis, Jeff. “Kristy’s Crisis.” People Weekly, May 9, 1983. http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0„20084944,00.html. “Kristy and Love!” Tiger Beat. Date unknown, p. 68.

McNeil, Elizabeth. “Kristy McNichol Wants to ‘Be Open about Who I Am.’” People Weekly, Jan 6, 2012. http://www.people.com/people/article/0„20559567,00.html.

McNeil, Elizabeth. “Kristy McNichol is ‘Overwhelmed with Love and Support.’” People Weekly, Jan 11, 2012. http://www.people.com/people/article/0„20559567,00.html.

White, Armond, “White Dog: Fuller vs. Racism.” Criterion Collection DVD Liner Notes. 2008. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/848-white-dog-fuller-vs-racism

White Dog. Directed by Samuel Fuller. 1981 Paramount Pictures. Criterion Collection, 2008. DVD.