USAG (USA Gymnastics) describes acrobatic gymnastics as a pair or group performance featuring tumbling, partner balances, and dynamic skills with flight. 1 Acrobatic gymnastics relies on the relationship between two, three, or four bodies moving in space and requires no apparatus other than a sprung floor and the human form. Born from a European system of sport and reliant on the gender binary, acrobatic gymnastics is a highly regulated sport with specific aesthetic expectations which emphasize small, white, thin, bodies, and highly feminized make up and costuming. At the highest levels, athletes compete on an international stage and perform in the name of nation for judges who score the performances based on artistry, difficulty, and execution.

In this essay I analyze a balance routine performed by Ani Caballero and Isabella Melendez, two Mexican-American gymnasts who, in 2012, were the first people to represent Team Mexico in Acrobatic Gymnastics. In examining their performance, I demonstrate how female acrobatic gymnastics queers the nation through intimate encounters of racialized female bodies in motion. My reading of women’s pairs Acrobatic Gymnastics is grounded in queer of color and feminist critique of national paradigms. Through a queer reading of the praxis of same sex paired acrobatics, my work pushes against the nation’s ideas of representations of gender and sexuality. In Performing Queer Latinidad: Dance, Sexuality, and Politics, Ramon Rivera-Servera defines queerness as practices and identities that lie outside of the logic of normative heterosexuality. 2 Rivera-Servera uses the term queer as both a position and strategy in this text to approach the ways in which people of marginal gender and sexual identities engage, create, and consume culture. Borrowing from his definition of queerness, this paper considers questions of queer national performance in same sex acrobatic gymnastics. I contend that Caballero and Melendez’s presents as Latina women in a Eurocentric sport, along with their roles as unofficial diplomats for Mexico, queers the nation through acts of disciplined female intimacy.

I do this by focusing on three aspects that are significant in the practice of pair acrobatics: repetition, failure, and the entanglement of bodies. First, I will concentrate on how repetition, failure, and the nuanced understanding of each other’s bodies facilitate intimacy between pairs. I then look at the ways in which minoritarian athletes carry borders, the intimacy of nation, and colonial histories in their bodies. I will finally attend to the queer performance enacted by same gender acrobatic athletes which is further complicated by race, ethnicity, citizenship, and nation. I concentrate to each of these aspects of acrobatic intimacy by close reading the archival footage of Caballero and Melendez’s balance routine performed at the 2012 Acrobatic World Championships in Buena Vista, Florida.

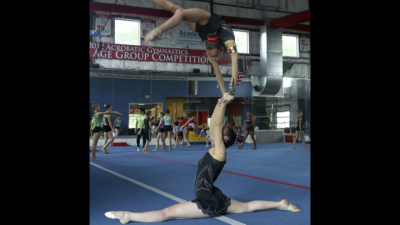

Ani Caballero and Isabella Melendez enter the 2012 Acrobatic World Championship’s competition floor holding hands. The girls are costumed in black unitards decorated with bedazzled red roses, gem encrusted forest green vines, and bursts of glittering gold. Every inch of their bodies shimmer under the bright performance lights. The strut to their opening positions with their free arm lifted references a flamenco pose. Their costumes and opening choreographic entrance foreshadow the Spanish themed routine, which is set to tango music and incorporates identifiably flamenco inspired dance movements. For half of the two-minute routine, the girls hold, press, lean, lift, and support one another’s bodies. In acrobatic gymnastics competitions, athletes compete three types of routines: dynamic, which requires lifts that involve flight; balance, in which the top partner must sustain positions while balanced on base partners body; and combined, which involves both flight and balance skills. These routines require different modes of execution to be successful. Balance routines, such as the one I am analyzing today, require the women to perform sustained contact. For any given skill to count, the performers must hold a static position for a minimum of three seconds. Over half of the routine includes touching, holding, balancing, and supporting one another.

In the Acrobatic Gymnastics Code of Points, athletes are not only scored on performance and choreography, but also on “partnership.” Article 31.1 of the Code of Points states that there must be a logical relationship and connection between the individuals inside of their partnership. 3

During this 2012 balance routine, the girls perform six partnered skills. Partnered skills in a balance routine require the girls to work in tandem to allow for Melendez to balance in various positions only using Caballero’s body for support. To execute the skills presented in acrobatic gymnastics, athletes must spend hundreds of hours together learning each other’s bodies. After mastering the mechanics of a skill, the girls must then work on the performative qualities of the routine. How do you support someone’s weight but appear graceful? When do you look at the judges and smile? How do you accommodate the unique and specific body of your partner? When you perform intimacy, you must think of every detail. By the time the athletes enter the competition floor, their “logical relationship and connection” has been drilled repeatedly and molded into a codified routine. Nothing should be spontaneous or unexpected. On a good day, every touch unfolds exactly as planned.

Skill One

Melendez stands directly in front of Caballero and the two girls smile out at the judges, palms forward. Both abruptly look at the ground to prepare for the skill. Caballero grips Melendez’s hands and braces her body. The two quickly throw their arms to 90-degree angle to build momentum, press down, and then Melendez sails upward into the air. Her left foot lands on Caballero’s shoulder. With a swift kick, Melendez transitions from a one-foot balance on Caballero’s shoulder to a handstand only using Caballero’s hands for support. Balanced upside down above Caballero, Melendez’s face hovers just a foot or so above Caballero’s nose.

While Melendez balanced over Caballero’s head, Caballero’s lips move almost imperceptibly. During interviews with each of the athletes, we watched this routine together. We stopped and started the video to discuss the skills, mistakes, and memories from the performance. I asked both women if they remember talking during their routines. Both emphatically responded, “yes, we always talked throughout the whole routine.” Caballero could not remember what she said to upside-down Melendez, citing that it would be early in the routine for any conversation. Melendez however remembered clearly, “Ani was counting” she said. As the base, Caballero remained safely on the ground for the duration of the routine, which allowed her to keep a clear sense of time. Her adrenaline rushed less than Melendez’s who, in addition to being lofted into compromising positions, struggled with fear and mental blocks. By counting for Melendez, Caballero kept the girls on time, and performed an act of care.

Caballero and Melendez had a complicated interpersonal relationship throughout their time working together. Caballero, who was ages 14 through 17 during the time she worked with Melendez, described their partnership as “hard for me to get along with her and hard for her to get along with me … In hindsight, I understand why she didn’t like me … I was pushing her to be better and when she didn’t respond to that, I would get really frustrated.” 4 Melendez was 11 years old when she became partners with 14-year-old Caballero. Their age difference and intricacies of their individual identities both created tension and required the two girls perform as a pair.

The Acrobatic Gymnastic team at Acrobatic Gymnastics of San Antonio (AGSA), run by head coach Vladimir Valdev, continues to be one of the most successful in the US. Due to the many talented athletes at the gym, Valdev has the discretion and ability to move partners around to create the best possible matches. As the only Mexican citizen at the gym who did not hold an American passport at the time, Cabellero had to have a Mexican partner. Caballero spent years training alone and watching her American teammates progress and succeed in the sport; she could not compete because of her citizenship. Melendez, who is Mexican American, joined the gym and Vladev recruited her to work with Caballero. Vladev also helped facilitate the process of obtaining Mexican citizenship for Melendez who initially only held American citizenship.

Borders have consequences on an intimate level. For years, Caballero’s citizenship rendered her without a partner. As a preteen girl, Caballero did not remember ruminating much on the larger political arguments between the US and Mexico. Instead, she felt the border in her body. The arbitrary delineation of nations as a result of colonialism and imperialism impacted Caballero’s embodied experience of Acrobatic Gymnastics. Yomaira Figueroa-Vasquez in her text Decolonizing Diaspora Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature writes about how coloniality has resounding impacts on the intimate aspects of citizens’ lives. According to Figueroa-Vasquez, the intimate impacts of coloniality range and take place at different scales including nationally and even regionally. 5 In this case, the impacts of coloniality affected a specific system of sport and its reverberations directly impacted Caballero’s ability to develop the intimate relationship needed to be successful in her sport.

Skill Two

Over halfway through their two-minute routine, the women perform a balance skill where Caballero lays on her back with her legs in a high V position and Melendez sits in a middle split balanced on Caballero’s feet. To enter this skill, Melendez holds Caballero’s feet and swings her left leg up to place her ankle in the arch of Caballero’s foot. To gracefully swing her second leg up she needs assistance from Caballero, who gently places a hand on Melendez’s right inner thigh. This small maneuver gives Melendez just the right amount of support to lift her right leg off the floor and secure it in the arch of Caballero’s other foot.

These small supportive moments appear graceful and easy on the competition floor but as detailed by Caballero in our conversation, each successful skill is born from a thousand failures. Disciplined intimacy requires repeatedly failing in rehearsal for the final product to appear effortless. Caballero says that the physical relationship between partners relies on trial and error:

You start to learn things by the way that you fail. By the way you can’t do things… it is funny because every time you learn a new skill, obviously the first few times, you are going to fall. And it is not going to look pretty. But then you start correcting those mistakes. The way you actually master a skill is because you have seen every single way that it could fail. And you start to understand those certain notions. 6

Understanding how the partnership fails, i.e., all the ways it can tip over, crumple, and collapse, gives the girls valuable information about their connection. In her essay about falling queens and freak technique, Anna Martine Whitehead considers the gesture of collapsing and the potential failure of falling. She posits that freedom exists not just in recognizing the inevitability of collapse but that it is both continuous and critical. 7 In acrobatic gymnastics, the history and memory of collapse allows the athletes to perform. These iterations of failure also provide valuable information about the intimate details of your partner’s body. In another skill, Caballero described how Melendez struggled to produce enough power to flip from Caballero’s shoulders properly. To accommodate her partner’s needs, Caballero manipulated her own body to ensure Melendez’s success by changing her weightlifting routine so the girls could properly execute the skill. This level of embodied attention to one another creates a physical entanglement between the two that reaches beyond the choreographic closeness they perform at competitions. Through hours of training, failing, and falling, these girls designed their bodies to fit together and accommodate each other’s weaknesses.

Skill Three

The girls face each other and Caballero places her hands on Melendez’s waist. They bend their knees together to gain momentum and Caballero presses Melendez above her head. Melendez assumes a position called ‘bird,’ where her back is arched, legs are pressed together to create a single line from head to pointed toes. Melendez’s arms out to the side like wings, Caballero stands below Melendez, feet hip distance apart with straight arms and fingers griping Melendez’s waist. She stares intently at Melendez’s belly button until Melendez gracefully twists her body and falls into a cradle position in Caballero’s arms to end the routine. This skill is reminiscent of countless ballet pas de deux performances, or Patrick Swasey and Jennifer Grey in their iconic final pose in Dirty Dancing.

The difference here is the base, the person doing the lifting, is a fifteen-year-old girl. Acrobatic women’s/girl’s pairs performance queers the traditional male-female dance partnership and puts a woman or girl in a strength-oriented role. In contemporary dance choreography today, the gendered roles in partnering are slowly becoming obsolete. However, gymnastics still valorizes gender roles and leaves little space for fluidity. The Code of Points specifically identifies the appropriate attire for men versus women 8 and explicitly states different performance expectations for men’s and women’s pairs. 9 The gender binary plays an important role in how FIG organizes and regulates gymnastics competition. Yet, they sponsor a discipline that requires same gender performance and it puts into question idea of the gendered performance roles.

In addition to Caballero’s role as the base questioning how the female body can perform, these routines also require same gender intimacy. In Kareem Khubchandani keyword titled Intimacies, he postulates that intimacy suggests proximity, closeness, and entanglement. 10 Khubchandani specifically investigates the term through his experiences studying queer nightlife and how bodies come into contact. In Acrobatic Gymnastics women wrap, balance, fold, cling, roll, slide and twist across, around, and against one another’s bodies. They train to account for one another’s strengths and weaknesses and learn to fail together in order to succeed. The sport and the governing body of gymnastics choose to emphasize athletic prowess while ignoring the ways in which same gender pairs engage with queer intimacy. This inadvertently fosters a space where queerness happens.

Caballero and Melendez’s performance, due to their positionality, further attends to this queering because of their outsider status in the sport. Jose Esteban Muñoz defines brown people as people who are rendered brown by their migration pattern, accents, or linguistic origins. 11 In this case Callabero and Melendez are rendered brown by the nation they represent and, in a sport, created for and by white bodies, it queers the nation for which they perform. Jillian Hernandez, in her text Aesthetic of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment, argues that women of color use self-styling, art making, and cultural production as a means to express subjectivity and freedom. 12 She suggests that although there is nothing inherently excessive in the bodies she studies, due to Eurocentric ideals of beauty and taste Black, Latina and Afro-Latina women are read as out of control and tacky which renders them queer.

Caballero and Melendez may wear similar leotards and make-up to those of the athletes of European nations, but the presents of the Mexican flag on their costumes mark them as other. Their Latina-ness makes them excessive on a stage that systematically excludes Global South. The governing system of gymnastics implements a hegemonic structure rooted in aesthetics of Whiteness and heterosexuality. Yet, the presents of same gender pairs gymnastics and furthermore the performances of minoritarian athletes like Isabella Melendez and Ani Caballero opens up queer futurities not just in sports governed by FIG but in athletic competition on a broader level. Through this sport I see space to question the gendered binary so tightly held by many forms of competitive sport and opportunities to queer representations of nation on global stages. Much of Acrobatic Gymnastics deserves criticism and reform, however I also see generative possibilities in a sport that values non-traditional roles of performance, the rehearsal of failure, and the intimate entanglement of female bodies in motion.

Bibliography

Acrobatic Gymnastics Technical Committee. “2009-2012 Code of Points for Acrobatic Gymnastics.” Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique, January 2009. .

Caballero, Ani. Ani Caballero Interview. Interview by Amelia Estrada, October 11, 2021.

Figueroa-Vásquez, Yomaira. Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature. Northwestern University Press, 2020. .

Hernandez, Jillian. Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment. Duke University Press, 2020.

Khubchandani, Kareem. “Intimacies.” Amerasia Journal 46, no. 2 (May 3, 2020): 236–37. .

Martin-Whitehead, Anna. “Expressing Life Through Loss, On Queen That Fall with a Freak Technique,” in Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Melendez, Isabella. Isabella Melendez Interview. Interview by Amelia Estrada, October 13, 2021.

Muñoz, José Estaban. The Sense of Brown. Duke University Press, 2020.

Rivera-Servera, Ramón. Performing Queer Latinidad : Dance, Sexuality, Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012.

“USA Gymnastics | Acrobatic Gymnastics Event Descriptions.” Accessed May 25, 2021. .

Footnotes

- “USA Gymnastics | Acrobatic Gymnastics Event Descriptions.” Accessed May 25, 2021. .

- Ramón Rivera-Servera, Performing Queer Latinidad : Dance, Sexuality, Politics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012), 26.

- FIG Executive Committee, “2017-2020 Code of Points Acrobatic Gymnastics,” February 2017.

- Ani Caballero, Zoom interview with Author, 2021.

- Yomaira Figueroa-Vasquez, Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature (Northwestern University Press, 2020), 31.

- Ani Caballero, Zoom interview with author, 2021.

- Anna Martine-Whitehead, “Expressing Life Through Loss, On Queen That Fall with a Freak Technique,” in Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 201), 282.

- Acrobatic Gymnastics Technical Committee, “2009-2012 Code of Points for Acrobatic Gymnastics” (Fédération Internationale de Gymnastique), 35.

- Acrobatic Gymnastics Technical Committee, 23-31.

- Kareem Khubchandani, “Intimacies,” Amerasia Journal 46, no. 2 (May 3, 2020): 236.

- José Estaban Muñoz, The Sense of Brown (Duke University Press, 2020), 3.

- Jillian Hernandez, Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment (Duke University Press, 2020), 17.

References

Cover Image Credit: Vincent Davis, San Antonio Express News