Abstract

This essay critically examines motels, delving into their role as souvenirs, exploring nostalgia surrounding them, and questioning their comfort complexities. It starts with the motel's evolution and its stereotypical image. The terms "shady" and "sketchy" are analyzed psychologically and in media portrayals like Bad Times At the El Royale. Motels are explored as nostalgic Americana, serving as kitschy time capsules evoking the past. They are also seen as souvenir symbols, evident in their structure and commercial intent. The essay ties these concepts to the thesis project, American Standard, set in a Missouri motel, showcasing varied and sometimes grim scenarios. Despite their nostalgic allure, motels can be associated with less comforting realities. Reflecting on their symbolic value, the essay concludes by considering questions of preservation, as well as the changing hospitality industry, amidst declining popularity.

It was a hot summer day in 1999: After driving for what it felt like an eternity, I was finally arriving for a beach vacation at the Thunderbird Beach Resort in Treasure Island, Florida. I was a child, just four years old, and, as children do, became captivated by bright, flashy things. I remember it vividly: a mid-century design, complete with a vibrant neon sign featuring an Aztec-style bird that illuminated for miles along the coastal shore. It was so beautiful! While this “resort” (if you will) was not considered a motel for its time, it possessed very similar eerie features—to the point where we left sooner than we anticipated. To this day, I remember nothing else about this trip; however, the aesthetic of the Thunderbird Resort lives rent-free in my nostalgic memory.

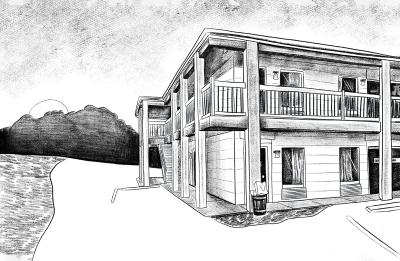

From a young age, motels have always been exciting creatures to me. I use this term to describe their strange and shady nature. Motels, due to their affordability, attract a diverse clientele, sometimes leading to a perception of them as less than reputable. My experiences and fascinations with motels inspired American Standard, a visual essay capturing roadside culture through various illustrations and short, environmental comics. The story, set in a small unnamed rural town in Missouri, explores a series of nonlinear stories that include the struggles within the confines of a motel, tying them together through a unique larger narrative. The motel acts as a purgatory for those who are on their way from one place to another. Based on true events, this book portrays a hypothetical reality far from comforting, glamorous, and sleek, yet can be entirely possible and even painfully relatable for some.

The notion of motels as "shady" creatures adds an additional layer of complexity that is also illustrated in American Standard. These people—also depicting shadiness—bring strange stories to the fictional Crawford Comfort Inn. This perception is explored through the visual elements of shade, both in terms of dishonesty and the play of light and shadow. The monochromatic illustrations in my project capture a timed aesthetic, create a somewhat fuzzy atmosphere, and emphasize the dream-like quality of memories and nostalgia associated with motels.

Motels are considered a "roadside hotel catering primarily for motorists, typically having rooms arranged in low blocks with parking directly outside" 1 but they were much more than that to me. Growing up in the Midwest, they plagued every major highway with their aesthetic appeal. As a simple and cheap solution, my large family of eight took advantage in any way we could during our travels. Motels with the fancy bells and whistles were far and few between; most of them were cheap and unattractive. And rightfully so—they were intended to serve the purpose of convenience for Americans during the development of interstates. Flashy, bright neon signage was used as a smart tactic to attract those passing by them. Their structures varied in layouts that made them accessible from all angles, and, as they began to pop up in more rural areas between major cities throughout the twentieth century they became more affordable for the everyday passerby. With the combined forces of motels and the expansion of major highways, America rapidly transformed its way of living, making it much quicker and more efficient to travel across the country at any given time. 2 This idea, along with their quirky and kitschy aesthetic, sparked a high level of curiosity that I wanted to dive into more.

My project navigates the intricate relationship between comfort and discomfort, drawing on historical, architectural, and cultural perspectives. Whether it is the microwave on top of the mini-fridge or the retro television displaying a famous late-night commercial, we share similar experiences as the characters in this book. Through visual storytelling and exploration of diverse definitions, I hope to evoke nostalgia and prompt reflection on the duality of comfort in the average midwestern motel.

Between executing research, writing, and this illustrative project, my goal was to break down metaphors of the iconic motel— cueing in on keywords such as comfort, nostalgia, and souvenirs, and their relationships with each other. Through this, I research the paradox of motels, often perceived as shady, and reflect on how they serve as a liminal space between destinations, embodying both comfort and the reality of discomfort. Looking at media and other resources, I study how the role of nostalgia and souvenirs help shape our perceptions of them. This essay, along with this project, investigates these topics and looks into other related concepts to construct the dichotomy between the motel’s deceptiveness and approachableness, emphasizing the importance of their evolution, structure, and legacy today.

Comfort vs. Discomfort

The central theme of this project revolves around the complex nature of comfort. I see this term as a rollercoaster of ups and downs, much like the experiences I've had with people, places, and memories. There are times where we feel pleasant, whereas other times may be very agonizing. The term comfort is derived from the Latin term "confortare," which means to “render strong and, by extension, to alleviate pain or fatigue.” 3 Encompassing various definitions, from cheer and support to relief and contentment, it manifests in physical, mental, social, and economic aspects, influencing how we navigate life's challenges and seek moments of solace.

My research explores how the evolution of motel spaces has shaped our contemporary understanding of comfort. Daniel A. Barber's lecture, “After Comfort,” offers insights into comfort as a promise of consistency and predictability, which resonates with my project:

The opposite of comfort is, obviously, discomfort. The first we seek, the second we try to avoid. Comfort is valued because it promises consistency, normalcy, and predictability, which allow for increased productivity or a good night’s sleep. Our collective allegiance to comfort is a form of self-assurance—that we are not threatened and that tomorrow will be like today. Comfort indicates that one has risen above the inconsistencies of the natural world and triumphed, not only over nature and the weather but over chance itself. We can rely on comfort. It will be there when we get back. 4

Motels, despite their cheap amenities, have normalized certain features in our homes, challenging us to appreciate comfort by temporarily embracing discomfort. While Barber’s lecture heads in a slightly different direction than my project, he makes a relatable point that is apparent in my visual essay, American Standard. Exploring comfort and livability in the context of a motel, my book portrays the lower-class audience's perception of this idea in a familiar environment. Motel rooms are "designed" to be a comfortable “home-away-from-home” for most 5 ; however, they tend to be quite the opposite through cheap mattresses and horrible tasting coffee packets.

Tomas Maldonado and John Cullars also delve into the influence of space on comfort, highlighting the complexity of this concept. In their essay The Idea of Comfort, they begin by exploring the word “livability,” its relationship with reality, and how it defines comfort in the sense of “convenience, ease, and habitability.” 6 They connect this privilege to the Industrial Revolution, and, like Barber, emphasize how space and class affect accessibility. For many, experiencing a sense of "comfort" was a luxury reserved for the affluent upper-classes who predominantly owned houses and businesses, while those in the lower-classes often found themselves living and working in impoverished conditions under their purview. The privilege of privacy, integral to comfort, designated the home as a hub for social engagement, thereby contributing to the emergence of what we now know as the modern nuclear family. Comfort epitomized the aspirational lifestyle of the wealthy elite. 7 Based on this research, I wanted to illustrate ways that lower-class people experienced easement within a space.

Echoes of Nostalgia

Motels evoke a complex interplay of comfort and discomfort tied to nostalgia, prompting the question of why they hold such appeal. Is it their familiarity? Is it their aesthetic? Is it the stories they create that are passed down for many generations? Before we dive into this, we must first look at Svetlana Byom's breakdown of this Greek-derived term accordingly: “nostos,” to return home, and “algia,” longing. She defines nostalgia as a longing to return home, eliciting sentiments of loss or a romantic fantasy. 8 Motels, especially through iconic elements like vintage neon signs, become symbols of America's cultural past, triggering positive reactions and fond memories.

Nevertheless, positive experiences are not always associated with nostalgia. Understanding the dual nature of this phenomenon, as explored by Sedikides, Wildschut, Ardnt, and Routledge in their article “Nostalgia: Past, Present, and Future,” informs my approach to American Standard. 9 Initially regarded as a dire omen by Swiss mercenaries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, nostalgia was deemed a malevolent force, purportedly manifesting as demons that possessed individuals exhibiting symptoms of melancholy such as weeping, irregular heartbeat, or anorexia. In the twentieth century, nostalgia was classified as a psychiatric disorder, but was later reclassified as a form of depression. 10 Today, it is generally regarded as a more regular and positive occurrence; however Sedikides, Wildschut, Ardnt, and Routledge state that it is still bittersweet for most. I aim to evoke both positive and sorrowful responses, mirroring the bittersweet reality of nostalgia in my own experiences. This dichotomy is crucial in portraying how nostalgia operates in our lives and contributes to the emotional depth of my visual essay.

To illustrate this dichotomy further, Boym separates nostalgia into restorative and reflective types. Restorative nostalgia idealizes the past as a perfect snapshot, seeking to reconstruct and revive it, often associated with cheerful memories. Reflective nostalgia, in contrast, embraces the longing process without attempting revival, sometimes leading to a sense of doom. Despite their differences, both forms empower and achieve a similar goal. 11 The Crawford Comfort Inn in my visual essay embodies both restorative and reflective nostalgia. The characters passing through relive sad moments, trapped in a time capsule that prevents reflection on their past traumas.

Motels, despite being a dying form of lodging, maintain their charm, connecting us with the past. Mark Okrant's insights in No Vacancy: The Rise, Demise, and Reprise of America's Motels emphasize the power of nostalgia, linking past experiences with our present identity. 12 Motels are a few places that still connect us with this past time; for as long as they are still standing, we will continue to remember and sustain our relationship between this past and present moment.

My project, American Standard, captures this essence through a sketchy style, a monochromatic palette representing time, and timely pop culture references. The visual essay serves as a preservation of motel culture, invoking nostalgia through its aesthetic and references to the mid-1990s. Motels are sort of like a souvenir themselves—they are memorable and make people feel a certain way, triggering nostalgia, especially for those who experienced the heyday of this culture. They are an experience that a younger audience will never have the opportunity to fully understand.

Timeless Souvenirs

Souvenirs are a tangible way of connecting us with the past. Travelers often buy them as a way of remembering experiences or to share them with others as evidence of their visit to a specific destination. Rather than obtaining knick-knacks, photography serves this purpose as well. Susan Sontag's perspective, as expressed in "In Plato's Cave," highlights the act of taking pictures during travel as a way of “converting experience into an image, a souvenir,” shaping our perception of the journey. 13 This idea parallels motel culture, where temporary stays become memorable snapshots in our lives.

Souvenirs have a special place in our hearts: when we travel, we experience, and as a result, we collect. These objects carry the weight of the past, creating a sense of nostalgia. In On Longing, Susan Stewart, explores how souvenirs serve as narratives authenticating the tourist's experience, albeit on a small scale. Souvenirs, due to their size, allow us to control and cherish them, becoming tangible links to memories:

Travel becomes a strategy for accumulating photographs. The very activity of taking pictures is soothing and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel. Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture. This gives shape to experience: stop, take a photograph, and move on. 14

Motels, like souvenirs, represent this idea of “moving on;” they are not permanent, however they leave a lasting impact on our experiences. Commercialized souvenirs, such as knick-knacks and mementos, play a significant role in connecting the past and present within motel history. 15 Not only do they serve as physical reminders of a particular period, but they also act as a preservation of a bygone era. By holding a keychain, postcard, or magnet in our hand, we are physically and mentally connected through nostalgia and historical continuity. In addition, souvenirs were also key components in advertisement and historical documentation, helping others who study them rebuild timelines of motel aesthetics and the evolution of the industry over time. In American Standard, I try to capture the essence of motels through single-page illustrations, serving as visual souvenirs that evoke nostalgia without the need for full narratives. Many items that are familiar to most appear atmospherically throughout the book, such as brochures, no smoking signs, and more.

Some small souvenirs represent a larger structure that we have visited. For example, most consumers identify the “Welcome to Las Vegas” sign as both a ginormous entity and a small object you can purchase at the gift shop. Beyond the United States, the Eiffel Tower is another popular one. In his essay “The Eiffel Tower,” Roland Barthes extends this discussion, viewing the monument itself as a souvenir—both an object and symbol for a larger, more authentic picture. While he refers to the structure as a “total monument,” he also considers it a glance, object, metaphor, and symbol. 16 While we see souvenirs mostly in the form of miniatures, we can consider the structure of the Eiffel Tower a souvenir itself; it is both an object and symbol for the city of Paris. Souvenirs are also objects and symbols for a bigger, more authentic picture.

Reflecting on my childhood experiences with motels, I aim to capture these notions in my visual essay, leveraging the authenticity of America's Best Inn as a reference for the Crawford Comfort Inn. The motel, in this context, becomes the souvenir of my thesis project, encapsulating a time capsule that immerses the viewer in a restorative nostalgic mode.

Roadside Attractions in Media

Motels have gained popularity in visual culture due to their aesthetic, making them fitting settings for psychological dramas, suspense, and apocalyptic stories. Because these stories were always appealing to me, I used these popular examples as research for creating the environments in my visual essay. Particularly, the film Bad Times At the El Royale (2018) became one of the most influential films that helped me create dark narratives surrounding liminal spaces.

In this neo-noir thriller directed by Drew Goddard, the iconic motel setting plays a central role, as in my work. Set in the 1960s, the film follows seven strangers converging at a hotel situated on a state border, each seeking redemption but finding themselves ensnared in unforeseen complications. The distinctiveness of the El Royale hotel, with its retro neon signage and well-designed structure, adds to the film's aesthetic appeal, highlighting its significance within American culture and contributing to its standout quality.

In Bad Times at the El Royale, the plot mirrors themes explored in my thesis project, focusing on diverse characters whose intertwining stories unfold within the confines of a peculiar hotel. Echoing the film's narrative, each individual grapples with personal struggles and moral dilemmas, their true selves often obscured by layers of deception. The setting of the El Royale, straddling the California-Nevada border, serves as a metaphor for the dualities present in the characters' lives, amplifying the tension and conflict as the story unfolds. 17

In American Standard, the Crawford Comfort Inn also serves as a mysterious character itself, embodying a strange, pulpy aura. Similar to Bad Times at the El Royale, the motel becomes a backdrop for characters grappling with comfort and moral decisions. The motel's location in rural southwestern Missouri, close to Route 66, adds depth to the narratives, exploring themes of monotony, loneliness, and even murder. Route 66, with its rich history, connects the characters' struggles with the optimism of dreamers traveling West. The stories, though often sad, offer a personal and believable glimpse into the complexities of comfort within the motel setting.

Three Motels in Missouri

During my research for this project, I secured a grant to explore motels in Springfield, Missouri, during a cold January weekend in 2022. My main goal with this trip was to take notes and reference photos on the environments and unusual motel ephemera. The motels ranged from upscale to subpar, defying my expectations and providing valuable experiences throughout the whole weekend.

The Munger Moss Motel on Route 66 in Lebanon, Missouri was the first pit-stop on my list. After my three hour drive, we finally arrived around nine o’clock in the evening. Despite its deceptive appearance, resembling a closed business, we discovered it was still operational. 18 After intruding after-hours, we had a strange encounter with the quirky owner, Ramona, who aggressively greeted us in pajamas. Learning quickly that there were no rooms available, we decided to move on to the next place. Ramona, with her quirky appearance and absurd behavior, became an inspiration for one of the narratives in my visual essay.

The second motel, Rest Haven Court, was beyond perfect: a nostalgic gem with a charming Americana stereotype. The vast, attractive neon sign and bright red doors in every room were so charming, and it had a uniqueness to it that other places we stayed lacked. Its unique features, like a playground, highlighted its family-friendly atmosphere, creating the sense of comfort I was looking for. It was easily noticeable that this particular motel was a popular lodging spot, preserving its allure over the years. Aside from its beautiful aesthetic, the interior was decent. I did meet some strange people, and, at one moment, woke up in the middle of the night hearing unnecessary noises that kept me questioning.

The final motel, America's Best Inn in Eureka, Missouri, held sentimental value, as my husband had lived there years ago. 19 Almost eight years later, everything looked the same. Brown and yellow swallowed the room—including the telephone, bathroom tiling, and carpet. Despite its sketchy appearance, the 1990s aesthetic and memories made it special. However, revisiting revealed a decline in condition, and we opted not to stay due to unpleasant surroundings and safety concerns. It quickly became everything short of pleasant: dirty bathrooms, peeling wallpaper, and the lingering smell of cigarettes. We left shortly after checking in. This experience emphasized the risk of revisiting places that hold nostalgic memories.

Conclusion

Motels encapsulate the intertwined concepts of comfort, nostalgia, and souvenirs; however, their inviting exteriors may not accurately reflect the condition of what is inside them. Despite their deceptive appearance, these structures hold a unique and curious atmosphere that sets them apart, making them intriguing in their strangeness. Through my research and my project American Standard, my goal was to create these connections visually. The Crawford Comfort Inn is portrayed with sketchy, shady importance, mirroring the narratives of its characters. Motels, while structurally permanent, function as temporary spaces, leaving us with only memories, pictures, or souvenirs. The iconic neon signs, design, and peculiar history of American motels are preserved and celebrated in mainstream media, elevating them from mundane to culturally significant gems. Overall, my research and project left me yearning for more as I focused highly on their past, but want to understand what their future will be. The decline of motels in popularity has led to rebranding efforts, with the rise of alternative lodgings potentially depriving the next generation of the unique motel experience. By preserving the essence of comfort, nostalgia, and souvenirs within the enigmatic atmosphere of motels, it becomes imperative to recognize and cherish their enduring significance, ensuring their legacy remains vibrant and relevant in the ever-evolving landscape of American culture.

Footnotes

“Motel.” Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=motel

Jakle, John A., Keith A. Sculle, and Jefferson S. Rogers. “Chapter Two” in The Motel in America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Maldonado, Tomas, and John Cullars. “The Idea of Comfort.” Design Issues 8, no. 1 (1991): 35–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511452.

Barber, Daniel. “After Comfort.” Paper presented at Climate Futures II: Design Politics, Design Natures, Aesthetics and the Green New Deal Symposium, Rhode Island School of Design, December 5, 2019. http://opentranscripts.org/transcript/after-comfort/

Jakle, Sculle, and Rogers. “Chapter Eight” in The Motel in America (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Maldonado, Tomas, and John Cullars. “The Idea of Comfort.” Design Issues 8, no. 1 (1991): 35–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511452.

For more on this, see McLaren, Chrstine. Comfort Crash Course, Day 8: Private Life (or, Why the Couch Is More Comfortable than the Park Bench). www.guggenheim.org/blogs/lablog/comfort-crash-course-day-8-private-life-or-why-the-couch-is-more-comfortable-than-the-park-bench

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia (New York, New York: Basic Books, 2008).

Sedikides, Constantine, Tim Wildschut, Jamie Ardnt, and Clay Routledge. “Nostalgia: Past, Present, and Future.” Sage Journals 17, no. 5 (October 1, 2008): 304–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x.

Sedikides, Constantine, Tim Wildschut, Jamie Arndt, and Clay Routledge. “Nostalgia: Past, Present, and Future.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 17, no. 5 (October 2008): 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x.

Boym. The Future of Nostalgia.

Okrant, Mark J. No Vacancy: The Rise, Demise, and Reprise of America's Motels (Concord, NH: Plaidswede Publishing, 2013).

Sontag, Susan. “In Plato’s Cave” in On Photography, 9 (New York: Delta Books, 1977).

Sontag. On Photography, 9-10

See Okrant, No Vacancy.

Barthes, Roland. “The Eiffel Tower” in The Eiffel Tower, and Other Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 1979), 3-18.

California is a state that is looking to the West with opportunity and neighbors. Nevada is a much less opportunistic state that pulls people away from this prosperity. This was a result of the Gold Rush of 1848, arguably one of the most significant events in American history. Many people left their families in order to seek this newfound wealth.

During our trip there were a few museums we visited that included a lot of rich history of The Munger Moss Motel. It originally started in 1936 as a sandwich shop off Route 66 in Devil’s Elbow, but due to the relocation of Route 66 its business declined. After switching owners, it was moved to a nearby town, expanded, and rebranded into The Munger Moss Motel in 1946.

My husband, who is from Ukraine, was able to come to America on a summer work program at an amusement park that I also worked at during that time. Their partnered program exploited the immigrants who had worked there and provided them with poor living conditions in nearby motels.

References

“About Us.” Munger Moss Motel. https://mungermoss.com/about-us/.

Barthes, Roland. “The Eiffel Tower” in The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies. New York: Hill and Wang, 1979.

Barber, Daniel. “After Comfort.” Paper presented at Climate Futures II: Design Politics, Design Natures, Aesthetics and the Green New Deal Symposium, Rhode Island School of Design, December 5, 2019. http://opentranscripts.org/transcript/after-comfort/

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York, New York: Basic Books, 2008.

Jakle, John A., Keith A. Sculle, and Jefferson S. Rogers. The Motel in America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

McLaren, Christine. “Comfort Crash Course, Day 8: Private Life (or, Why the Couch Is More Comfortable than the Park Bench).” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, March 16, 2012. https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/lablog/comfort-crash-course-day-8-private-life-or-why-the-couch-is-more-comfortable-than-the-park-bench.

Maldonado, Tomas, and John Cullars. “The Idea of Comfort.” Design Issues 8, no. 1 (1991): 35–43. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511452.

Okrant, Mark J. No Vacancy: The Rise, Demise, and Reprise of America's Motels. Concord, NH: Plaidswede Publishing, 2013.

“Motel,” Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/122623?isAdvanced=false&result=1&rskey=u8fsRQ&

Sedikides, Constantine, Tim Wildschut, Jamie Ardnt, and Clay Routledge. “Nostalgia: Past, Present, and Future.” Sage Journals 17, no. 5 (October 1, 2008): 304–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x.

Sontag, Susan. “In Plato’s Cave” in On Photography, 3-24. New York: Picador, 1977.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing. Duke University Press, 2012.