Abstract

This theoretical article responds to three common arguments used to say that art created through generative artificial intelligence (GAI) should not be considered art: lack of effort, no human agency, and the use of the work of previous artists instead of the creation of original pieces. To answer these points, the author of this article uses data from an autoethnographic study and other theoretical approaches to achieve three things. First, the author examines the practices of AI artists on X. Second, it draws parallels between the process of creating this content and the outcomes of generative art. Finally, it compares AI-generated art and artworks undoubtedly considered artistic. This paper presents the following counterarguments: First, the creation of art using GAI often involves intricate processes. Second, the way in which AI artists cede agency to the machine is similar to the extensive history of generative art that predates GAI. Third, art has a rich history of borrowing and reinterpreting, revealing that AI-generated art is not a departure from tradition but a continuation of it. The conclusion of this work is that AI-generated art is not an entirely new or contentious concept but rather an evolution of artistic expression. As such, it should be viewed simply as a new tool wielded by creators.

Imagine a world where paintings come into existence autonomously, music emerges from lines of code, and poetry is born from the minds of machines. We find ourselves on the verge of a transformative era, where machines delve into realms previously reserved for human creativity. Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) possesses the capability to produce images, music, poetry, and various forms of content, simulating the styles of renowned artists spanning from the likes of Leonardo da Vinci, Beethoven, and Baudelaire to contemporary figures such as Banksy, Drake, and the scriptwriters of The Office. However, most people have a bias towards AI-generated art. A study in which human-made art was randomly labeled as human-made or AI-made showed that people were more likely to negatively judge a piece of art if they knew it was generated using AI. 1 Moreover, many oppose the idea of considering AI-generated content as art. 2 Their criticism predominantly revolves around three key concerns. First, there's the issue of minimal effort required to generate this content. 3 Second, there's the absence of human agency and intentionality in the process, which is the reason why a judge in the US denied an attempt to overturn the US Copyright Office's decision to not grant copyrights to AI art. 4 Finally, there's a perception that AI systems don't truly create anything original but rather repurpose the works of numerous artists as reference. 5

Over the course of a year, I conducted an autoethnographic study, engaging in the creation of AI art using various platforms and actively participating in an AI art community on X (the platform formerly known as Twitter). This article draws from the outcomes of this comprehensive undertaking. I also apply several theoretical approaches to the issues highlighted by GAI critics. The aim of this theoretical article is not to dismiss any problematization of this technology. For example, issues such as the use of artists’ work without their consent to train models and the potential impact on artists’ livelihoods and income are significant and worthy of attention. However, these concerns, while important, are beyond the scope of this paper. The goal of this work is to challenge the notion that AI-generated art lacks artistic merit, a criticism often voiced by GAI critics. To accomplish this, I will draw connections between AI-generated art and traditional art forms that we unequivocally consider artistic. This comparison will demonstrate that GAI is merely a novel instrument for artists to express themselves, akin to brushes, canvases, or other computer-generated creations. I will focus on image-based GAI to explore the notion that art generated by AI should not be considered entirely novel or inherently polemic but rather as an additional tool for human expression and creativity. The argument posits that AI-generated art shares fundamental attributes with various prior instances of generative art, as well as with well-established artistic techniques like collage, remixes, and even movements such as Dadaism, all of which involve reappropriating existing pieces for creative expression.

This consideration bears significant weight, given that AI technology stands as the most rapidly adopted business technology in history. 6 It is increasingly apparent that creative industries and content creators are incorporating GAI to generate multimedia materials, as exemplified in the introduction clip of Marvel's Secret Invasion TV series or the use of GAI by Hasbro/Wizards of the Coast to produce images for a Dungeons and Dragons book. Both of these instances have caused an uproar within the community of artists. 7 Also, pieces of AI art have begun to be presented in exhibitions all around the world. 8 Moreover, cultural critics are scrutinizing these AI-generated contents as they become integral parts of our cultural repertoire. As scholars and members of academia, it is our duty to engage in this discourse, offering our expertise and literature reviews to navigate this new era of creation. Let us, then, delve into the captivating world of AI-generated art, where pixels and algorithms converge to craft a new chapter in the story of human expression.

Art Needs Talent and Skill: Effort and Agency in AI-Art

AI-generated art presents a dilemma for certain art critics and theorists due to the significant role AI plays in the creative process. For many individuals, a crucial aspect of art’s value lies in the effort applied, a quality inherently linked to the concepts of agency and intentionality. This explains why some individuals dismiss specific artworks with comments like, “even my 3-year-old could create something like that.” Of course, after more than a century of abstract art, now we accept that just because something seems easy to make that does not mean that it does not have artistic value. A great example of this is Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Boxing Ring) 1983 painting. 9

Nevertheless, we still consider that some degree of effort is required. We tend to attribute greater value to creation when we believe it requires a higher degree of effort to produce. 10 We may accept that even a banana taped to a wall can be considered art because it is the result of a thought process that involved creativity and some concept. 11 A study revealed that individuals exhibited a more positive response to abstract paintings when they believed these artworks were created by humans rather than generated by computers. 12 GAI critics argue that any person can create images by simply writing a line of text, 13 and although this is absolutely true, often it is not the case that AI-art creators simply write a simple line describing what they want the machine to generate.

The AI Art community on X is notably active, with thousands of members frequently engaging in the exchange of prompts. These prompts vary in style and complexity, and they play a central role in guiding the generation of AI-created art. Certain creators employ prompts in various forms such as poems, haikus, or vividly detailed descriptions to inspire their AI-generated artworks to spark the process of AI-generated artworks. For example, Patricia Leveque (@patricialeveq), an AI artist uses poetry and haikus written by her for her prompts:

Moiré patterned shadows,

Curve upon her form in shallows,

Their depth, it bellows. 14

Additionally, when sharing their generated images, they often include the original, aesthetically crafted prompts that resulted in the piece. Others invest considerable time experimenting with newly coined words and combinations until they discover formulations that consistently yield the desired artistic effects. These discovered words become akin to techniques, with terms like "neonfrostfire," "neoncrystalabstraction," "hexluminescent," or "pyroethereal" strategically included in prompts to instruct the AI in generating specific visual effects. Furthermore, certain artists merge and modify existing prompts, combining words, tweaking language, and even mixing in elements from diverse sources to create unique prompt formulas for precise artistic outcomes.

Within the community, there are individuals with backgrounds in art history who request the AI to emulate or blend the styles of various artists. Those with expertise in photography include technical details such as shutter speed, ISO, aperture, lighting, and camera angles in their prompts, while designers integrate their design knowledge.

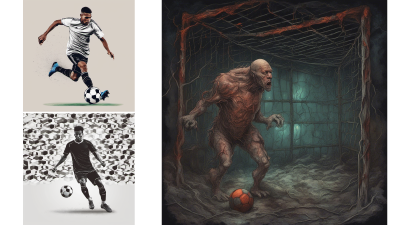

Lastly, some members possess programming knowledge and a deep understanding of the mathematical processes driving the AI's generation. They adjust parameters like the seed or guidance scale to steer the AI toward producing their envisioned creations. Although there are GAI platforms that offer preconfigured models that emulate certain styles, techniques or genres, the AI art community on X tends to gravitate more toward intricate, multi-faceted prompts that yield highly specific and creative results. You can simply write “man playing soccer” or you can write “A scratched, grunge painting of a neoncrystalabstraction neonfrostfire hexluminescent fatberg teratoma monstrous wrinkly man playing soccer, inside a thorn cage, in pain, roots and branches sprouting from him. Cenobite aesthetic, in the style of dark surreal illustration artwork, full color, vector-based shading, pop art, thick black outlines” as prompt. What is common among the AI art community of X is more similar to the second option than the first one.

There are other ways in which AI-artists overt control over GAI and fine-tune it as any other artist controls their own instruments. “Some artists train their GAI with specific data sets and images, selected by them. For example Lev Pereulkov.” 15

In this sense, the GAI is used as a tool for exactly what its name implies, the generation of art. “According to artist Mario Klingemann, one of the pioneers in AI-art: ‘If you heard someone playing the piano, would you ask?: “Is the piano the artist?” No. So, same thing here. Just because it is a complicated mechanism, it doesn’t change the roles.’” 16 Of course, the pianist has all the agency in the music produced, while the AI artist cedes some of this agency (or in some cases all of the agency) to the medium. This, however, does not negate the artistic value of the output. To illustrate this, we should focus on the word generative.

Generative art is nothing new. The term “refers to any art practice in which the artist uses a system, such as a set of natural language rules, a computer program, a machine, or other procedural invention, that is set into motion with some degree of autonomy, thereby contributing to or resulting in a completed work of art.” 17 Examples include computer-generated art like fractals, Spirograph drawings, Sol LeWitt's wall drawings (which exist “as a set of instructions that can be recreated on another wall by another person” 18 ), Cole Newman’s use of gravity and a pendulum to make unique patterns 19 , and William Burroughs' shotgun art (where “there’s no possibility of predicting what patterns you’re going to get” 20 ). These practices are considered art, despite the creator delegating their agency over the outcome to generative process, partially or completely.

It's crucial to recognize that AI lacks consciousness. Despite its ability to simulate human-like functions, AI remains a series of computational processes. It is only a system with the “ability to correctly interpret external data, to learn from such data, and to use those learnings to achieve specific goals and tasks through flexible adaptation.” 21 Therefore, a piece of AI-generated art is not co-authored by a human and a machine. Instead, it is the creation of a human using a machine. To illustrate, we can consider any generative art scenario like Cole Newman’s artwork: tying a paint can to a pendulum and making it swing, painting a canvas in the process does not make the pendulum a co-author of the piece. The object merely acts as a tool in this art-making process due to its lack of sapience and sentience. The output of the GAI does not come from its understanding of the piece that is being generated but from a series of responses to a prompt, based on algorithmic computational instructions, as John Searle’s famous Chinese room explained. 22 Therefore, GAI is nothing but a tool. Like all instances of generative art from the past, AI art consists of pieces created through procedural systems. There is no intentionality within the algorithms of the machine.

However, even in instances in which there are no aleatory or procedural systems involved in the art creation, the question of agency is complex if we use Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory as a framework. More specifically, Bruno Latour’s concept of the shared agency of the assemblage—or network—of human and non-human actors. 23 According to Latour, agency resides beyond human choices, and it is the result of the sum of different forces enacted by different entities. For example, while creating a painting, the artist’s choices influence the result, but equally involved are the work of every other artist that has influenced the creator, the work of art gallery curators and book publishers who made their work accessible to the artist, the people who work in the companies that created the paint, the brushes, the canvas. Moreover, the outcome is also influenced by non-human actors like those tools used to paint, the electric energy that powers the lighting at the artist’s studio and keeps the air conditioner on, or, if there’s no air conditioning, the heat of the summer that influences the artist, the natural phenomena that inspired them, etc. In this sense, humans are not the only factor when determining outcomes. This makes the argument about artists ceding agency to machines in the case of AI art more complex because, using Latour’s framework, the agency goes beyond human hands for every art piece, human-made or generated through any procedural system.

I want to emphasize, though, that even though the agency is shared between users and GAI, the artist would still be the author, and AI is just another tool. However, Latour’s framework is useful to acknowledge the role of programmers and creators of GAI models and platforms in the outcome. They share the agency of the artist, just as gallery curators and painting tool makers do.

Finally, we assign aesthetic value to multiple things not originating from human creators. “For example, consider natural structures like a snowflake, flowers, a spider web, or a landscape. They all can be the object of aesthetic admiration. However, what they require is a (human) observer.” 24 In this context, it's often said that beauty is subjective. Research indicates that individuals have emotional responses to AI-generated art, perceiving intentionality behind these emotions. 25 Ultimately, the audience's aesthetic experience remains a paramount aspect of any artwork.

Hence, the presence of human agency and control over the creative outcome can't be the sole criteria for classifying a creation as art. Throughout history, we have instances of artwork where artists didn't have absolute control or agency over the result. As the 2019 report on AI and art by the Oxford Internet Institute concludes, the utilization of GAI in art creation doesn't signify the complete automation of art; instead, it serves as a complementary use of technology. 26 One of the authors emphasized in an interview that “human agency in the creative process is never going away. Parts of the creative process can be automated in interesting ways using AI . . . but the creative decision-making which results in artworks cannot be replicated by current AI technology.” 27 Therefore, AI art still necessitates some degree of human intervention.

Good Artists Steal: Appropriating, Repurposing and Recontextualizing Art

Critics of GAI argue that art carries a sense of originality and uniqueness, unlike AI-generated pieces that predominantly draw from existing human art and rearrange it into what they term “Frankenstein-like creations.” 28 To tackle this criticism, let's examine historical examples of traditional art.

In 1913, Marcel Duchamp initiated an experimental art piece by combining a bicycle wheel and a chair. Four years later, he famously presented a urinal, signed as R. Mutt, titled “Fountain,” marking the inception of his Ready-Mades. These two pieces can be appreciated in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Within two more years, he playfully added a beard, mustache, and some risqué-sounding letters to Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa. These creations, alongside similar works by other artists, ushered in the Dadaist movement. Dadaists created pieces of art by recycling and using elements from other artists, newspapers, and magazines, in the form of collages and absurd pastiche. 29 Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Man Ray are some of the artists who embraced and represented Dadaism in the United States. Many other artists began experimenting in similar ways. “A handful of other artists began to develop photo-collage techniques. Photo-collage became another method of creating new media artifacts from existing mass media images.” 30

But this is not the only way in which artists used the art of previous artists to create their own pieces. “Post-modern artists and designers frequently used bricolage and created works consisting of quotations and references to art from the past, rejecting modernism's focus on novelty and breaking with the past.” 31 This became one of the main characteristics of every postmodern art expression:

The dialogical mode of pastiche becomes a central concern of aesthetic production in the postmodern arts. Confronted with the archive of the artistic tradition, the postmodern writer, visual artist, architect, composer consciously acknowledges this past by demonstratively borrowing. 32

Yet, collages and pastiche are not the exclusive methods through which artists have drawn from previous works. In 1890, Vincent van Gogh's The Good Samaritan emerged as a creation deeply influenced by Eugene Delacroix's 1849 rendition. Numerous artists have produced paintings that are not only inspired by but profoundly shaped by the contributions of their fellow artists. As the quote attributed to Picasso says “Lesser artists borrow; great artists steal.” 33 An excellent example can be found in the Pop Art movement, epitomized by Andy Warhol's iconic works like the Campbell Soup cans and Marilyn Monroe portraits, which prominently feature the utilization of pre-existing imagery to forge new art. Another famous member of the Pop Art movement, Roy Lichtenstein, used the style of comic books to create his paintings, in a similar way a GAI user could create new artwork using comic book style, or any other specific style today. Such incorporation of existing images and styles from the past into fresh creative contexts stands as one of the fundamental tenets of postmodernism.

On the other hand, many pieces of art have inspired multiple pop culture references and parodies like, for example, Edward Hopper’s famous painting Nighthawks (1942) being parodied with characters from The Simpsons, superhero comics, and many other pop culture characters. 34 This practice extends to various art forms, including cinema. For instance, in Terry Gilliam's film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) we see a clear borrowing from Botticelli's The Birth of Venus in the presentation of Uma Thurman as the goddess. A parallel illustration of reusing previous works to craft new art can be also observed in the realm of music, notably through practices such as covers, remixes, or the incorporation of samples from earlier compositions into fresh tracks. This is particularly prevalent in specific genres, like hip-hop.

Thus, drawing from the creative reservoir of past artists to inspire new art does not diminish the aesthetic or artistic worth of the resulting piece. Throughout history, we have engaged in the practice of replicating, recontextualizing, referencing, reimagining, and remediating the works of our artistic predecessors to craft innovative and unique artworks.

Even when artists produce entirely original works, devoid of any copying or direct inspiration from previous art, they inherently rely on cultural frameworks during the creative process. 35 Our artistic endeavors draw from a vast reservoir of art and cultural influences that have shaped our lives. This influence manifests in both conscious acts of intertextuality and more subtle, unconscious processes, allowing us to leverage the rich tapestry of our cultural experiences when creating art:

Our life is an ongoing process of both supervised and unsupervised cultural training. We take art and art history courses, view websites, videos, magazines, and exhibition catalogs, visit museums, and travel in order to absorb new cultural information. And when we ‘prompt’ ourselves to make some new cultural artifacts, our own biological neural and networks (infinitely more complex than any AI nets to date) generate such artifacts based on what we’ve learned so far: general patterns we’ve observed, templates for making particular things, and often concrete parts of existing artifacts. In other words, our creations may contain both exact replicas of previously observed artifacts and new things that we represent using templates we have learned, such as golden ratio or use of complementary colors. 36

In essence, what GAI achieves through its training process shares commonalities with the creative approach adopted by artists. Furthermore, an additional factor warrants consideration in relation to this training and its subsequent results. “Yes, artificial neural networks are trained on previously created human art and culture artifacts. However, their newly generated outputs are not mechanical replicas or simulations of what has already been created. In my opinion, these are frequently genuinely new cultural artifacts with previously unseen content, aesthetics, or styles.” 37 When observing the content shared within the AI art community on X, we discover more than mere reproductions of traditional art, discover not mere replicas of traditional artwork, but rather original pieces characterized by innovative and distinct styles, themes, and fusions.

AI-volution: GAI as the Next Step in the Evolution of Art Tools

All technology serves as an extension of our human abilities and expertise, as famously expounded by Marshall McLuhan. 38 When we reference technology, we encompass all human inventions, ranging from a simple pencil to advanced AI. Over the past decades, various computer tools have been instrumental in art creation, and GAI represents the latest addition to this continuum:

Artificial aesthetics can be described as an augmentation of our aesthetic skills, deepening both our creative processes and our understanding and sensibility of cultural artifacts. Advanced systems would then be a further evolution of devices that are already used in creative disciplines, such as graphic programs, computer-aided design technology, music software, and so on. 39

The utilization of automated systems in image creation is not a recent development. For decades, we've employed automated tools like autofocus, color correction, and filters. These processes operate independently of human agency and have played a role in the creative process of numerous artworks. GAI is not an exception but a continuation of this trend. Research indicates that artists leveraging AI to refine their creative abilities produce works deemed more aesthetically pleasing by their audience. 40 Research also has shown that artists effectively convey intended emotions and establish connections with their viewers. 41 Many members of the AI art community on X had extensive experience in traditional art before venturing into the realm of GAI.

Conclusion

The discourse surrounding Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) and its contributions to visual, musical, and textual content is rife with both anticipation and skepticism. This exploration of AI-generated art and its role in the realm of creativity and aesthetics has delved deeply into this ongoing debate, aiming to illuminate the multifaceted nature of AI-generated art and its relevance in our ever-evolving artistic landscape.

The central argument presented in this paper posits that AI-generated art is not an entirely new or contentious concept but rather an evolution of artistic expression. It should be viewed as a new tool wielded by creators. Criticisms regarding the perceived lack of effort and human agency in GAI art often overlook the intricate processes at work within the AI art community. The generation of unique and innovative prompts, coupled with the active role of human creators in shaping AI-generated art, challenges the notion that these creations lack artistic merit. Furthermore, this criticism overlooks the extensive history of generative art that predates GAI and also lacks human agency in its outcomes. Finally, the role of GAI platforms, models, and their programmers and creators has been explained through Bruno Latour’s framework of the shared agency of networks.

We’ve also drawn connections between AI-generated art and various historical artistic practices, such as collage, imitation, and movements like Dadaism. This comparison highlights the enduring tradition of repurposing and recontextualizing existing art to birth new forms of creative expression. The historical instances we've examined, from Marcel Duchamp's Ready-Mades to Andy Warhol's Pop Art, demonstrate that art has a rich history of borrowing and reinterpreting, revealing that AI-generated art is not a departure from tradition but a continuation of it. Moreover, we highlighted the similarities between GAI training and every artist's cultural framework.

The world of art stands at the crossroads of a profound transformation, one that challenges traditional notions of creativity and authorship. As we journey through this landscape, navigating the intriguing realm of AI-generated art, we must remember that art has always been a reflection of human innovation and adaptability. AI is not the artist; it is the tool. It is a brush, a musical instrument, a digital canvas, and like any tool, its value lies in the hands that wield it. In this era where pixels and algorithms converge to craft a new chapter in the tale of human expression, this new fusion of human creativity and technology will surely mark a profound and lasting partnership in humankind’s artistic journey.

Footnotes

Lucas Bellaiche, et al. “Humans versus AI: Whether and Why We Prefer Human-Created Compared to AI-Created Artwork.” Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 8, no. 1 (2023): 42.

David Orozco. “What’s the Real Deal between AI Art & IP?” Michelson IP, February 22, 2023. https://michelsonip.com/whats-the-real-deal-between-ai-art-ip/

Marcel Mensah, “Why Is Ai ‘Art’ Making Creators so Uncomfortable? A Creative’s POV.” LONER Magazine, December 12, 2022. https://www.lonerofficial.com/post/why-is-ai-art-making-creators-so-uncomfortable-a-curators-pov

Kris Holt, “Judge Rules That AI-Generated Art Isn’t Copyrightable, since It Lacks Human Authorship.” Engadget, August 21, 2023. https://www.engadget.com/judge-rules-that-ai-generated-art-isnt-copyrightable-since-it-lacks-human-authorship-150033903.html

Sarah Shaffi, “‘It’s the Opposite of Art’: Why Illustrators Are Furious about AI.” The Guardian, January 23, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/jan/23/its-the-opposite-of-art-why-illustrators-are-furious-about-ai

Cenk Sidar, “Council Post.”

See, for example, Johnston, Dais. “‘AI Is a Tool.’ The Problem With ‘Secret Invasion’ Is More Complicated Than You Think.” Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.inverse.com/entertainment/secret-invasion-ai-opening-titles-sequence; Millman, Zosha. “Yes, Secret Invasion’s Opening Credits Scene Is AI-Made — Here’s Why.” Polygon, June 21, 2023. https://www.polygon.com/23767640/ai-mcu-secret-invasion-opening-credits; Dean, Ethan. “Wizards of the Coast Forced to Rework New D&D Book amid AI Artwork Scandal.” Dexerto, August 7, 2023. https://www.dexerto.com/gaming/wizards-of-the-coast-forced-to-rework-new-dd-book-amid-ai-artwork-scandal-2239083/.

See, for example, Vankin, Deborah. “Everyone’s Talking about Refik Anadol’s AI-Generated Paintings.” Los Angeles Times. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2023-02-18/refik-anadols-ai-generated-living-paintings-frieze-2023; Exquisite Workers. “AI Surrealism: The World’s Largest AI Art Exhibition, NYC, 2023.” Medium, May 30, 2023. https://exquisiteworkers.medium.com/ai-surrealism-the-worlds-largest-ai-art-exhibition-2023-8980be9d3e6a; Ulea, Anca. “Digital Works Go ‘Beyond the Screen’ at London Art Show.” Euro News, May 6, 2023. https://www.euronews.com/culture/2023/05/05/beyond-the-screen-new-london-exhibition-highlights-digital-art-creations.

To see the painting in question, go to https://arthive.com/jeanmichelbasquiat/works/482021~Untitled_Boxing_ring

Justin Kruger, et. al. “The Effort Heuristic.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40, no.1 (January 1, 2004): 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00065-9.

The 2019 conceptual art piece Comedian by Mauritzio Cattelan featured a banana taped to a wall. For more information, see https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/dec/06/maurizio-cattelan-banana-duct-tape-comedian-art-basel-miami

Ulrich Kirk, et al. “Modulation of Aesthetic Value by Semantic Context: An fMRI Study.” Neurolmage 44, no. 3 (2009): 1125–32.

Peter McLard, “Sorry, Generating AI Art Does Not Make You an Artist.” Medium. October 28, 2022. https://medium.com/mlearning-ai/sorry-generating-ai-art-does-not-make-you-an-artist-108fe16d4de7

The original post can be found here: https://x.com/patricialeveq/status/1713206642463146140?s=20

Lev Manovich, “Seven Arguments about AI Images and Generative Media” in Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli (New York: CUNY, 2022), 7.

Emanuele Arielli, and Lev Manovich, “AI-Aesthetics and the Anthropocentric Myth of Creativity.” Nodes 1, no. 19–20 (2022): 115.

Philip Galanter, “Generative Art Theory” in A Companion to Digital Art, ed. Christiane Paul (Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, 2016), 146–80.

Cole Newman, “About.” Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.colescolor.com/about

“William S. Burroughs Shows You How to Make ‘Shotgun Art.’ Open Culture.” Accessed October 19, 2023. https://www.openculture.com/2012/09/william_s_burroughs_shows_you_how_to_make_shotgun_art.html

Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein.,“Siri, Siri, in My Hand: Who’s the Fairest in the Land? On the Interpretations, Illustrations, and Implications of Artificial Intelligence.” Business Horizons 62, no. 1 (January 1, 2019): 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004

For an explanation of this, see Larry Hauser, “Searle’s Chinese Box: Debunking the Chinese Room Argument.” Minds and Machines 7, no. 2 (May 1, 1997): 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008255830248

Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Emmanuelle Arielli, “Techno-Animism and the Pygmalion Effect,” in Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli, (New York: CUNY Press, 2022), 11.

Andreas Kaplan and Michael Haenlein, “Siri, Siri, in My Hand: Who’s the Fairest in the Land? On the Interpretations, Illustrations, and Implications of Artificial Intelligence.”

Anne Ploin, et al. “How Machine Learning is Changing Artistic Work” (Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute, 2019). https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/040222-AI-and-the-Arts_FINAL.pdf

Ploin quoted in "Art for Our Sake: Artists Cannot Be Replaced by Machines – Study | University of Oxford,” (Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute, March 3, 2022) https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2022-03-03-art-our-sake-artists-cannot-be-replaced-machines-study.

Brandon Moore, “The Case Against AI.” Medium. October 19, 2023. https://medium.com/graphic-language/my-case-against-ai-ad6489e124f2

Curtis Carter, “Dadaism” in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, Vol. 1, edited by Michael Kelly (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012) , 487–90.

Lev Manovich, “Seven Arguments about AI Images and Generative Media” in Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli,( New York: CUNY, 2022), 10.

Manovich, “Seven Arguments about AI Images and Generative Media,” 8.

Ingeborg Hoesterey, “Postmodern Pastiche: A Critical Aesthetic.” The Centennial Review 39, no. 3 (1995): 496.

Picasso, qtd. in Ben Shoemate, “What Does It Mean — Good Artists Copy, Great Artists Steal.” Medium. July 10, 2020. https://medium.com/ben-shoemate/what-does-it-mean-good-artists-copy-great-artists-steal-ee8fd85317a0

See, for examples, Celia Leiva Otto, “Nighthawks as Memes – Best Renditions.” Daily Art Magazine. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/nighthawks-memes-renditions/

Stuart Hall, “Encoding, Decoding” in The Cultural Studies Reader, edited by Simon During (London: Routledge, 1991), 507-517.

Manovich, “Seven Arguments about AI Images and Generative Media,” 14.

Manovich, “Seven Arguments about AI Images and Generative Media,” 6.

Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media; the Extensions of Man (New York: Signet Books, 1966).

Emanuele Arielli, “Even an AI Could Do That” in Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli, ( New York: CUNY, 2022), 9.

Jimpei Hitsuwari,et al. “Does Human–AI Collaboration Lead to More Creative Art? Aesthetic Evaluation of Human-Made and AI-Generated Haiku Poetry.” Computers in Human Behavior 139 (February 1, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107502

Demmer, et al. “Does an Emotional Connection to Art Really Require a Human Artist?”

References

Bibliography

Arielli, Emanuele. “Even an AI Could Do That.” In Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli,. http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/artificial-aesthetics

———. “Techno-Animism and the Pygmalion Effect.” In Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli. http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/artificial-aesthetics

Arielli, Emanuele, and Lev Manovich. “AI-Aesthetics and the Anthropocentric Myth of Creativity.” Nodes 1, no. 19–20 (2022). http://manovich.net/content/04-projects/118-ai-aesthetics-and-the-anthropocentric-myth-of-creativity/lm_ea_paper_for_nodes.pdf

“Art for Our Sake: Artists Cannot Be Replaced by Machines – Study | University of Oxford,” March 3, 2022. https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2022-03-03-art-our-sake-artists-cannot-be-replaced-machines-study.

Bellaiche, Lucas, Rohin Shahi, Martin Harry Turpin, Anya Ragnhildstveit, Shawn Sprockett, Nathaniel Barr, Alexander Christensen, and Paul Seli. “Humans versus AI: Whether and Why We Prefer Human-Created Compared to AI-Created Artwork.” Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications 8, no. 1 (2023). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s41235-023-00499-6

Carter, Curtis. “Dadaism.” In Encyclopedia of Aesthetics, Vol. 1, edited by Michael Kelly, 487–490. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Newman, Cole. “About.” Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.colescolor.com/about

Dean, Ethan. “Wizards of the Coast Forced to Rework New D&D Book amid AI Artwork Scandal.” Dexerto, August 7, 2023. https://www.dexerto.com/gaming/wizards-of-the-coast-forced-to-rework-new-dd-book-amid-ai-artwork-scandal-2239083/.

Demmer, Theresa Rahel, Corinna Kühnapfel, Joerg Fingerhut, and Matthew Pelowski. “Does an Emotional Connection to Art Really Require a Human Artist? Emotion and Intentionality Responses to AI- versus Human-Created Art and Impact on Aesthetic Experience.” Computers in Human Behavior 148 (November 1, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107875.

Exquisite Workers. “AI Surrealism: The World’s Largest AI Art Exhibition, NYC, 2023.” Medium. May 30, 2023. https://exquisiteworkers.medium.com/ai-surrealism-the-worlds-largest-ai-art-exhibition-2023-8980be9d3e6a.

Galanter, Philip. “Generative Art Theory.” In A Companion to Digital Art, ed. Christiane Paul, 146–80. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118475249.ch5.

Hall, Stuart. “Encoding, Decoding.” In The Cultural Studies Reader, edited by Simon During, 507-517. London: Routledge, 1991.

Hauser, Larry. “Searle’s Chinese Box: Debunking the Chinese Room Argument.” Minds and Machines 7, no. 2 (May 1, 1997): 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008255830248.

Hitsuwari, Jimpei, Yoshiyuki Ueda, Woojin Yun, and Michio Nomura. “Does Human–AI Collaboration Lead to More Creative Art? Aesthetic Evaluation of Human-Made and AI-Generated Haiku Poetry.” Computers in Human Behavior 139 (February 1, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107502.

Hoesterey, Ingeborg. “Postmodern Pastiche: A Critical Aesthetic.” The Centennial Review 39, no. 3 (1995): 493–510.

Holt, Kris. “Judge Rules That AI-Generated Art Isn’t Copyrightable, since It Lacks Human Authorship.” Engadget, August 21, 2023. https://www.engadget.com/judge-rules-that-ai-generated-art-isnt-copyrightable-since-it-lacks-human-authorship-150033903.html.

Johnston, Dais. “‘AI Is a Tool.’ The Problem With ‘Secret Invasion’ Is More Complicated Than You Think.” Accessed October 13, 2023. https://www.inverse.com/entertainment/secret-invasion-ai-opening-titles-sequence.

Kaplan, Andreas, and Michael Haenlein. “Siri, Siri, in My Hand: Who’s the Fairest in the Land? On the Interpretations, Illustrations, and Implications of Artificial Intelligence.” Business Horizons 62, no. 1 (January 1, 2019): 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004.

Kirk, Ulrich, Martin Skov, Oliver Hulme, Mark S. Christensen, and Semir Zeki. “Modulation of Aesthetic Value by Semantic Context: An fMRI Study.” Neurolmage 44, no. 3 (2009): 1125–32.

Kruger, Justin, Derrick Wirtz, Leaf Van Boven, and T.William Altermatt. “The Effort Heuristic.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40, no. 1 (January 1, 2004): 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00065-9.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford University Press, 2007.

Leiva Otto, Celia. “Nighthawks as Memes – Best Renditions.” Daily Art Magazine. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/nighthawks-memes-renditions/.

Manovich, Lev. “Seven Arguments about AI Images and Generative Media.” In Artificial Aesthetics: A Critical Guide to AI, Media and Design, edited by Lev Manovich and Emanuele Arielli, 4–28. New York: CUNY Press, 2022.

McClard, Peter. “Sorry, Generating AI Art Does Not Make You an Artist.” Medium. October 28, 2022. https://medium.com/mlearning-ai/sorry-generating-ai-art-does-not-make-you-an-artist-108fe16d4de7.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media; the Extensions of Man. New York: Signet Books, 1966.

Millman, Zosha. “Yes, Secret Invasion’s Opening Credits Scene Is AI-Made — Here’s Why.” Polygon, June 21, 2023. https://www.polygon.com/23767640/ai-mcu-secret-invasion-opening-credits.

Moore, Brandon. “The Case Against AI.” Medium. October 19, 2023. https://medium.com/graphic-language/my-case-against-ai-ad6489e124f2.

Orozco, David. “What’s the Real Deal between AI Art & IP?” Michelson IP, February 22, 2023. https://michelsonip.com/whats-the-real-deal-between-ai-art-ip/.

Ploin, Anne, Rebecca Eynon, Isis Hjorth, and Michael A. Osborne. “AI and the Arts: How Machine Learning Is Changing Artistic Work.” Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute, 2019. https://www.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/040222-AI-and-the-Arts_FINAL.pdf

Shaffi, Sarah. “‘It’s the Opposite of Art’: Why Illustrators Are Furious about AI.” The Guardian, January 23, 202. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/jan/23/its-the-opposite-of-art-why-illustrators-are-furious-about-ai.

Shoemate, Ben. “What Does It Mean — Good Artists Copy, Great Artists Steal.” Medium. July 10, 2020. https://medium.com/ben-shoemate/what-does-it-mean-good-artists-copy-great-artists-steal-ee8fd85317a0.

Sidar, Cenk. “Suddenly AI: The Fastest Adopted Business Technology In History.” Forbes. Accessed September 8, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2023/04/05/suddenly-ai-the-fastest-adopted-business-technology-in-history/.

Mensah, Marcel. “Why Is Ai ‘Art’ Making Creators so Uncomfortable? A Creative’s POV.” Loner Magazine, December 12, 2022. https://www.lonerofficial.com/post/why-is-ai-art-making-creators-so-uncomfortable-a-curators-pov.

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Dir. Terry Gilliam. Columbia Pictures, 1988.

The Morgan. “Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawing 552D.” Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/sol-lewitt#:~:text=Over%20the%20course%20of%20his,another%20wall%20by%20another%20person.

Ulea, Anca. “Digital Works Go ‘Beyond the Screen’ at London Art Show.” Euro News. May 6, 2023. https://www.euronews.com/culture/2023/05/05/beyond-the-screen-new-london-exhibition-highlights-digital-art-creations.

Vankin, Deborah. “Everyone’s Talking about Refik Anadol’s AI-Generated Paintings.” Los Angeles Times. Accessed November 13, 2023. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2023-02-18/refik-anadols-ai-generated-living-paintings-frieze-2023.

“William S. Burroughs Shows You How to Make ‘Shotgun Art.’ Open Culture.” Accessed October 19, 2023. https://www.openculture.com/2012/09/william_s_burroughs_shows_you_how_to_make_shotgun_art.html.